I don’t usually see Vinnie in a pensive mood. Moody, occasionally, but there he is at his usual table by the door, staring at the astronomy poster behind Al’s cash register. “Have a scone, Vinnie. What’s on your mind?”

“Thanks, Sy. Welcome back, Cathleen. What’s bugging me is the hard edges on that picture of Jupiter. It looks like those stripes are painted on. Everyone says Jupiter’s not really solid so how come the planet looks so smooth?”

“Cathleen, this is definitely in your astronomer baliwick.”

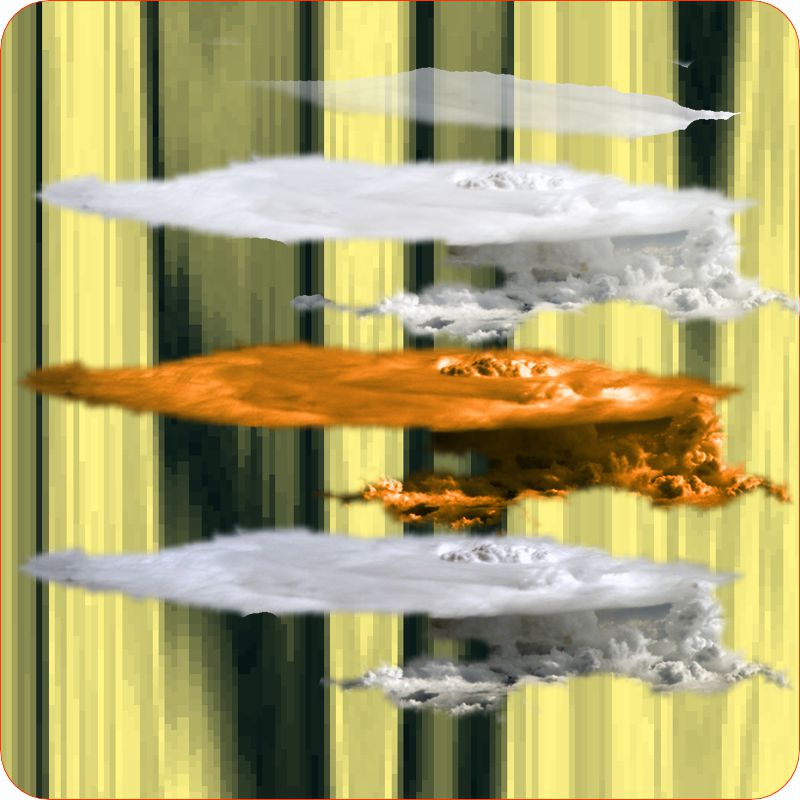

“I suppose. It’s a matter of scale, Vinnie. The white zones mark updrafts. The whiteness is clouds that rise a couple hundred kilometers above a brownish lower layer. The downdraft belts on either side are transparent enough to let us see the next lower layer. ‘A couple hundred kilometers‘ sounds like a lot, but that’s only a tenth of a percent of Jupiter’s radius. If Jupiter were a foot‑wide ball floating in front of us, the altitude difference would be as thin as a piece of tissue paper. You might be able to feel the ridges and valleys but you’d have a hard time seeing them.”

“But why does the updraft stop so sharp? Is there like a cap on the atmosphere?”

“The clouds stop, but the updrafts don’t. The cloud tops aren’t even close to the top of Jupiter’s atmosphere, any more than Earth clouds reach the top of ours. C’mon, Vinnie, you’re a pilot. Surely you’ve noticed that most thunderheads top out at about the same altitude. Isn’t the sky still blue above them?”

“That’s higher than the planes I fly are cleared for, but I wouldn’t want to get above one anyway. I know a guy who flew over one that was just getting started. He said it’s a bumpy ride but yeah, there’s still kind of a dark blue sky above.”

“All of that makes my point — our atmosphere doesn’t stop at the tropospheric boundary where the clouds do. Beyond that you’ve got another 40‑or‑so kilometers of stratosphere. Jupiter’s the same way, clouds go up only partway. For that matter, Jupiter has at least four separate cloud decks.”

“Wait, Cathleen — four? I know how Earth clouds work. Warm humid air rises, expanding and cooling as it goes. When its temperature falls below the dew point or freezing point, its humidity condenses to water droplets or ice crystals and that’s the cloud. I suppose if that same bucketful of air keeps rising far enough the pressure gets so low the water evaporates again and that’s the top of the cloud. How can that happen multiple times?”

“It doesn’t, Sy. In Jupiter’s complicated atmosphere each deck is formed from a different gas. Top layer is a wispy white hydrocarbon fog. The white zone clouds next down are ices of ammonia, which has to get a lot colder than water before it condenses. Water ice probably has a layer much farther down.”

“What’s the brownish layer?”

“There’s one or maybe two of them, each a complex mixture of ammonium ions with various sulfide species. The variety of colors in there make the visible light spectroscopy an opaque muddle.”

“Hey, if the brownish layers block what we can see, how do we even know lower layers are a thing?”

“Good question, Vinnie. Actually, we can do spectroscopy in the middle infrared. That gives us some clues. We’d hoped that the Galileo mission’s deep‑diver probe would sense the lower layers directly but unfortunately it dove into a hot spot where the upwelling heat messes up the layering. Our last resort is modeling. We have an inventory of lab data on thousands of compounds containing the chemical elements we’ve detected on Jupiter. We also have a pretty good temperature‑pressure profile of the atmosphere from the planet’s stratosphere down nearly to the core. Put the two together and we can paint a broad‑brush picture of what compounds should be stable in what physical state at every altitude.”

“Those ‘broad‑brush‘ and ‘should‘ weasel‑words say you’re working with averages like Einstein didn’t like with quantum mechanics. Those vertical winds mix things up pretty good, I’ll bet.”

“Fair objection, Vinnie, but we do what we can.”

~~ Rich Olcott