Vinnie taps on the magazine. “Sy, you’ve done it again. We ask you one question, you spend a lot of time talking about something else entire. They got this article here” <tap> “says the NANOGrav team captured the hum of the Universe. Al and me, we ask you about that and you get us discussing pulsars. Seems to me,” <tap tap> “that if you got a pulsar and the pulses got only a 3% duty cycle they’d sound more like clicks and,” <taptaptaptap> “if it’s a 10 millisecond pulsar that’s a hundred per second and they’d be more like a low‑pitched buzz, nothing like a hum.”

“One more short detour, Vinnie, sorry. Remember when we discussed the VLA, the Very Large Array of radio telescopes in northern New Mexico?”

“Sorta. I do remember visiting the place, out in the desert miles away from anywhere. They’ve got a couple dozen dish antennas each as wide as a four‑lane road, all spread out along railroad tracks. Big dishes for catching weak signals I understand, but I forget why there’s lots of dishes instead of one huge one or how that even works.”

“One reason is simple mechanics. A huge dish would try to sail away in the desert wind. VLA admins even have to safe‑mount those 25‑meter ones when things get gusty. But the real reason goes to how the array works as one big instrument. Here’s a hint — the dishes can be miles apart and lightspeed isn’t infinite.”

“Ah, that joggled my memory. It’s about when a signal comes in from some nova or something, each dish registers it with a slightly different arrival time and then the computers play match‑up games with all the time differences to figure exactly what angle the signal came from, right?”

“Roughly. The VLA’s multi‑dish design is about being able to resolve signal sources that are close together in the sky so yeah, slightly different angles. The Event Horizon Telescope team used the same strategy and a collection of radio dishes all over the world to produce those orange‑ring images of supermassive black holes. NANOGrav and the other Pulsar Timing Arrays sort of the flip the strategy.”

“At last we get to NANOGrav. Wait, they use lots of antennas to send signals to a star?”

“Nothing like that, Al. No, they use just a few antennas but they track the timing of many pulsars. About 70 at last count.”

“But we know what the timing is, to nanoseconds you said.”

“One word, Vinnie. ‘Frames‘.”

“Aw geez, Sy. Again?”

“Mm-hm. In the pulsar’s frame, it’s majestically rotating at a steady pace, tens or hundreds of times per second relative to its neighbors. Its beam proudly announces its presence on an absolutely regular schedule save for a small but steady slow‑down. In our frame, though, things can happen to a pulse as it heads our way.”

“Like what?”

“It might pass through a molecular cloud. We know those exist. Photons in the right wavelength ranges could interact with cloud components. That’d delay them, stretch the pulse, might even create interference between successive pulses. On the theory side, some cosmologists think the Universe may hold objects like cosmic strings or curvature‑induced domain walls that could delay, deflect or otherwise mess up a pulse. The best possibility, though, is that a gravitational wave could cross the path of a pulse en route to us.”

“Why is that a good thing?”

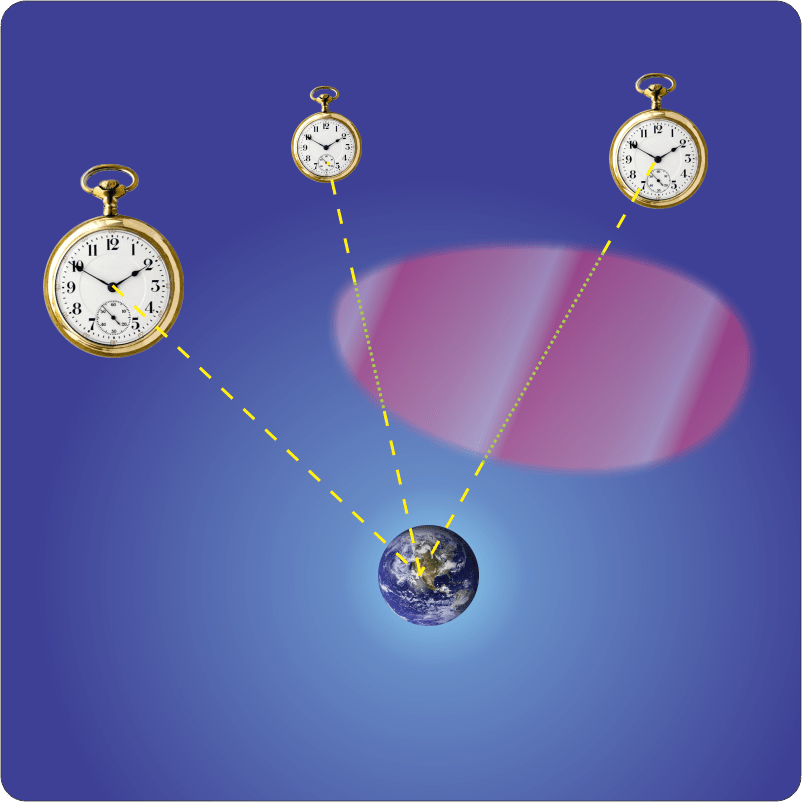

“Because they’d interact to alter that pulse’s timing. Gravitational waves stretch and squeeze time as they squeeze and stretch space. If a wave crosses a traveling pulse, the pulse will get here either early or late depending. Better yet, if we track enough pulsars scattered across the sky we might even see a parade of offset timings as the wave encounters different pulse beams. Hasn’t happened yet, though. The NANOGrav reports so far are about the background variation as waves from everywhere traverse the paths we’re watching.”

“The article says a hum.”

“Hum sounds come in waves per second. The gravitational background happens in waves per decade, such a low frequency even elephants couldn’t hear it.”

“OK, it’s rumble, not a hum. But why either one?”

~~ Rich Olcott