The deal’s gone round to Susan. “Another thing, Kareem — your assumption ignores Chemistry.”

“Didn’t Cathleen take care of that with her nuclear reactions in the star’s core?”

“Not even close. Nuclear reactions in general are literally a million or more times more energetic than chemical ones. Your classic AA alkaline battery is 1½ volts, right, but the initial step in Cathleen’s proton‑to‑helium process would net 1½ megavolts if we could set it up in a battery. Regular chemistry just re‑arranges atoms, doesn’t have a chance when nuclear’s going on.”

“Like trying to carve a cameo with dynamite, huh?”

“Not quite. If nuclear is dynamite, then bench chemistry is a bandsaw. I’d say the analog for carving a cameo would be cell biology. That operates at the millivolt level.”

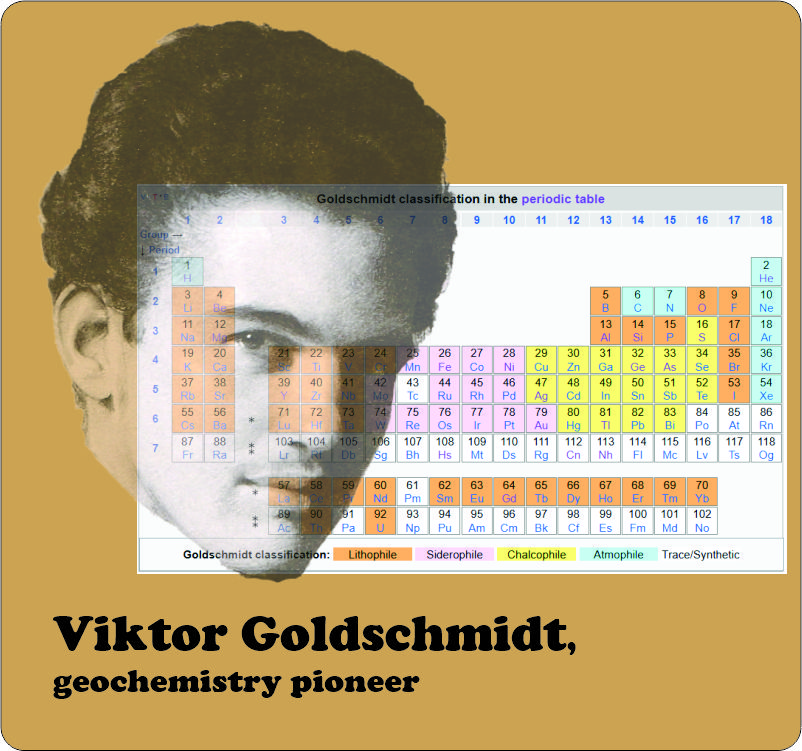

Cathleen holds up her tablet again. “Speaking of abundance graphs, here’s another one I built for my Astronomy class. I divided each element’s atom count in Earth’s crust by its atom count in the Universe. I color-coded the points according to Goldschmidt’s classification scheme. The lines mark the average ratio for each class. Compared to the Universe, oxide‑formers are ten times more concentrated in the crust than sulfide‑formers are, 150 times more concentrated than iron‑mixers, 900 times more than gases. I see the numbers but I don’t feel comfortable with them. Kareem, what do I tell my students?”

“Happy to explain the what, but Susan will have to explain the why. Goldschmidt started as a mineralogist, invented Geochemistry while bouncing around between Sweden, Norway and Germany until he barely escaped from the Nazis and was smuggled into England. He pioneered using crystallographic and thermodynamic analysis in geology. His scheme slotted each chemical element into one of those five classes. For example, he lumped the five lightest inert gases together with hydrogen, nitrogen and carbon into what he called the Atmophile class because they mostly stay in the atmosphere.”

“Carbon?”

“Yeah, that one’s iffy because coal and limestone. His reasoning involved carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and methane which don’t show up in rocks. There are other edge cases, like radon which ought to count as a gas but shows up in rocks and basements because it’s locked where it was generated as part of uranium’s decay sequence. We mostly find uranium in oxide minerals so Goldschmidt put it and radon into his Lithophile class of metals that occur in oxides. That’s opposed to mercury, silver and a dozen or so other elements that generally show up in sulfide minerals — that’s his Chalcophile class. There’s another dozen or so that dissolve into molten iron so they’re Siderophiles. We don’t see much of those in Earth’s crust because they were swept down to the core as the molten planet differentiated. Finally, there’s a whole batch of radioactives that huddle together as Other. But why those elements do those things, I dunno. Susan, your turn.”

“It’s a lovely application of Pearson’s Hard‑Soft Acid‑Base theory. Hard chemical thingies have a high charge‑to‑volume ratio. Also, their charge is tightly bound so it doesn’t polarize. Oxide, carbonate and fluoride ions are Hard, and so are alkali and alkali metal ions like sodium and calcium. Uranium’s Hard when it’s at high oxidation state like in a uranyl ion UO22+. (Eddie, stop snickering, that’s its proper name.) Soft thingies are just the reverse — big thingies with mushy electron clouds. Iodide is Soft and so are mercury, silver and gold ions. Bulk metals are extremely Soft, chemically speaking, because their electron clouds are so diffuse. The point is, Hard thingies combine best with Hard thingies, Soft thingies with Soft.”

“So the Lithophiles are Hard metals that make Hard‑Hard stony oxides. I suppose that extends to fluorides and carbonates?”

“Sure.”

“Then the sulfide ores, Goldschmidt’s Chalcogens, are Soft‑Soft compounds. The Siderophile metals combine with each other better than anyone else, and the Atmophiles don’t combine with anything. Cool.”

“Ah‑HAH! Then on my graph the Hard oxides are most common in the crust because they’re light and so float above the heavier Soft sulfides and the ultra‑Soft metals that sink to the core. Our planet is layered by Hardness.”

“Does the same logic apply to asteroids?”

“Sort of.”

~~ Rich Olcott