“But Uncle Sy, you never did answer my real question!”

“What question was that, Teena?”

“About the helium planet. With oxygen. Oh, I guess I never did get around to asking that part of it. You side‑tracked us into how a helium‑oxygen atmosphere would be unstable unless it was really cold or the planet had more gravity than Earth so the helium wouldn’t fly away. But what I wanted to know was, what would it be like before the helium left? Like, could we fly a plane there?”

“Mmm, let’s get a leetle more specific. You asked about swapping all of Earth’s atmospheric nitrogen with helium. Was that one helium atom for each nitrogen molecule or each nitrogen atom?”

“What difference would that make?”

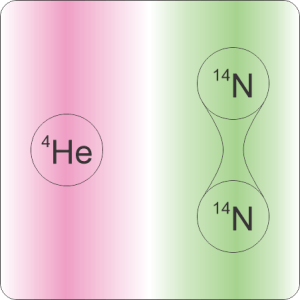

“Mass, to begin with. A helium atom weighs about 1/3 of a nitrogen atom, 1/7 of a nitrogen molecule. The atmospheric pressure we feel is the weight of all the air molecules above us. Swap out 80% of those molecules for something lighter, pressure goes down whether we swap helium for molecules or helium for atoms. We could calculate either one. But the change would be much harder to calculate for the atom‑for‑atom swap.”

“Why?”

“Mmm, have you gotten into equations yet in school?”

“You mean algebra, like 3x+7=8x+2? Yeah, they’re super‑easy.”

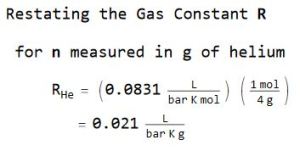

“This won’t even be as complicated as that. Here’s a famous Physics equation called The Ideal Gas Law — PV=nRT. Each letter stands for one quantity. Two adjacent quantities are multiplied together, okay? The pressure in a container is P, the container’s volume is V, T is the absolute temperature, and n is a measure of how much gas is in there.”

“You skipped R.”

“Yes, I did. It’s a constant number. Its job is to make all the units come out right. For instance, if the pressure’s in atmospheres, the volume’s in liters, n is in grams of helium and the temperature is in kelvins, then R is 0.021. Suppose you’re holding a balloon filled with helium and it’s at room temperature. What can you say about the gas?”

“Umm, all the nRT stuff doesn’t change so P times V, whatever it is, doesn’t change either.”

“If we let it fly upward until the pressure was only half what it is here…?”

“Then V would double. The balloon would get twice as big. Unless it burst, right?”

“You got the idea. Okay, now let’s fiddle with the right-hand side. Suppose we double the amount of helium.”

“P times V must get bigger but we don’t know which one.”

“Why not both?”

“Wooo… Each one could get some bigger… Oh, wait, I’m holding the balloon so the pressure’s not going to change so the balloon gets twice bigger.”

“Good thinking. One more thing and we can get back to your difference question. The Ideal Gas Law doesn’t care what kind of gas you’re working with. All the n quantity really cares about is how many particles are in the gas. A particle can be anything that moves about independently of anything else — helium atom or nitrogen molecule, doesn’t matter. If you change the definition of what n is measuring, all that happens is you have to adjust R so the units come out right. Then the equation works fine. Next step—”

“Wait, Uncle Sy, I want to think this atom‑or‑molecule thing through for myself. I’m gonna ignore R times T because both of them stay the same. So if we swap one atom of helium for one molecule of nitrogen, the number of particles doesn’t change and PV doesn’t change. But if we swap one atom of helium for each atom of nitrogen then n doubles and so does PV. But if we do that for the whole atmosphere then we can’t say that the pressure won’t change because the atmosphere could just expand and that’s the V but the pressures are all different as you go higher up anyway. Oh, wait, T changes, too, because it’s cold up there. It’s complicated, isn’t it?”

“It certainly is. Can we stick to just the simple atom‑for‑molecule swap?”

“Uh‑huh.”

~~ Rich Olcott

- Thanks again, Xander, and happy birthday. Your question was deeper than I thought.