Vinnie’s still wincing. “That neutron star pulling all the guy’s joints apart — yuckhh! So that’s spaghettification? I thought that was a black hole thing.”

“Yes and no, in that order. Spaghettification’s a tidal phenomenon associated with lopsided gravity fields, black holes or otherwise. You know what causes the tides, of course.”

“Sure, Sy. The Sun pulls up on the water underneath it.”

“That’s not quite it. The Sun’s direct‑line pull on a water molecule is less than a part per million of the Earth’s. What really happens is that the Sun broadly attracts water molecules north‑south east‑west all across the Sun‑side hemisphere. There’s a general movement towards the center of attraction where molecules pile up. The pile‑up’s what we call the tide.”

“What explains the high tide on the other side of the Earth? You can’t claim the Sun pushes it over there.”

“Of course not. It goes back to our lopsided taste of the Sun’s gravitational field. If it weren’t for the Sun’s pull, sea level would be a nice round circle where centrifugal force balances Earth’s gravity. The Sun’s gravity puts its thumb on the scale for the near side, like I said. It’s weaker on the other side, though — balance over there tilts toward the centrifugal force, makes for a far‑side bulge and midnight tides. We get lopsided forces from the moon’s gravity, too. That generates lunar tides. The solar and lunar cycles combine to produce the pattern of tides we experience. But tides can get much stronger. Ever hear of the Roche effect?”

“Can’t say as I have.”

“Imagine the Earth getting closer to the Sun but ignore the heat. What happens?”

Credit: NASA, CXC, Melissa Weiss (CXC)

“Sun‑side tides get higher and higher until … the Sun pulls the water away altogether!”

“That’s the idea. In the mid‑1800s Édouard Roche noticed the infinity buried in Newton’s F=GMm/r² equation. He realized that the forces get immense when the center‑to‑center distance, r, gets tiny. ‘Something’s got to give!’ he thought so he worked out the limits. The center‑to‑center force isn’t the critical one. The culprit is the tidal force which arises from the difference in the gravitational strength on either side of an object. When the force difference exceeds the forces holding the object together, it breaks up.”

“Only thing holding the ocean to Earth is gravity.”

“Exactly. Roche’s math applies strictly to objects where gravity’s the major force in play. Things like rubble‑pile asteroids like Bennu and Dimorphos or a black hole sipping the atmosphere off a neighboring blue supergiant star. We relate spaghettification to rubble piles but it can also compete with interatomic electronic forces which are a lot stronger.”

“You’re gonna get quantitative, right?”

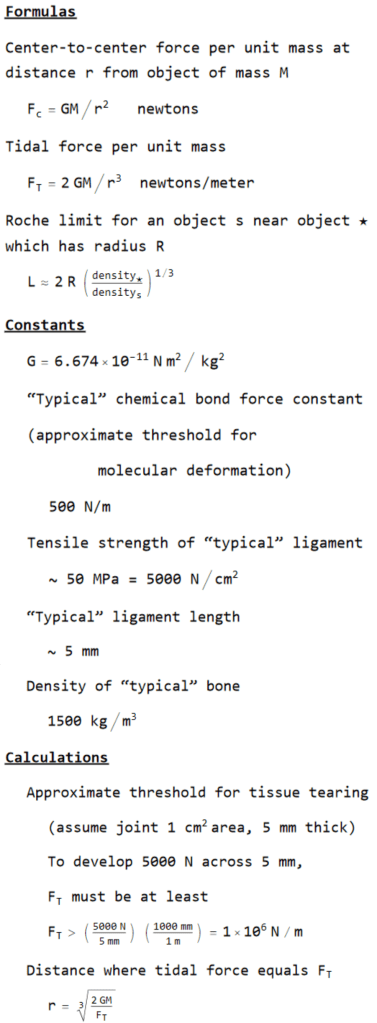

“Of course, that’s how I operate.” <tapping on Old Reliable’s screen> “Okay, suppose Niven’s guy Shaffer is approaching some object from far away. I’ve set up tidal force calculations for some interesting cases. Turns out if you know or can estimate an object’s mass and size, you can calculate its density which is key to Roche’s distance where a rubble pile flies apart. You don’t need density for the other thresholds. Spagettification sets in when tidal force is enough to bend a molecule. That’s about 500 newtons per meter, give or take a factor of ten. I estimated the rip‑apart tidal force to be near the tensile strength of the ligaments that hold your bones together. Sound fair?”

“Fair but yucky.”

“Mm‑hm. So here’s the results.”

“What’s with the red numbers?”

“I knew you’d ask that first. Those locations are inside the central object so they make no sense physically. Funny how Niven picked the only object class where stretch and tear effects actually show up.”

“How come there’s blanks under whatever ‘Sgr A*’ is?”

“Astronomer‑ese for ‘Sagittarius A-star,’ the Milky Way’s super‑massive black hole. Can’t properly calculate its density because the volume’s ill‑defined even though we know the Event Horizon’s diameter. Anyhow, look at the huge difference between the Roche radii and the two thresholds that affect chemical bonds.”

“Hey, Niven’s story had Shaffer going down to like 13 miles, about 20 kilometers. He’d’ve been torn apart before he got there.”

“Roughly.”

~~ Rich Olcott