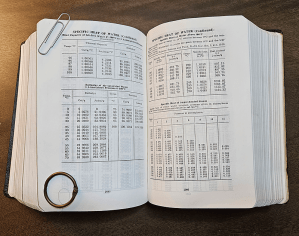

“Okay, Mr Moire, my grandfather’s engineering handbook has Specific Heat tables because Specific Heat measures molecular wabbling. If he’s got them, though, why’s Enthalpy in the handbook, too?”

“Enthalpy’s not my favorite technical term, Jeremy. It’s wound up in a centuries‑old muddle. Nobody back then had a good, crisp notion of energy. Descartes, Leibniz, Newton and a host of German engineers and aristocratic French hobby physicists all recognized that something made motion happen but everyone had their own take on what that was and how to calculate its effects. They used a slew of terms like vis viva, ‘quantity of motion,’ ‘driving force,’ ‘quantity of work,’ a couple of different definitions of ‘momentum‘ — it was a mess. It didn’t help that a lot of the argument went on before Euler’s algebraic notations were widely adopted; technical arguments without math are cumbersome and can get vague and ambiguous. Lots of lovely theories but none of them worked all that well in the real world.”

“Isn’t that usually what happens? I always have problems in the labs.”

“You’re not alone. Centuries ago, Newton’s Laws of Motion and Gravity made good predictions for planets, not so good for artillery trajectories. Gunners always had to throw in correction factors because their missiles fell short. Massachusetts‑born Benjamin Thompson, himself an artilleryman, found part of the reason.”

“Should I know that name?”

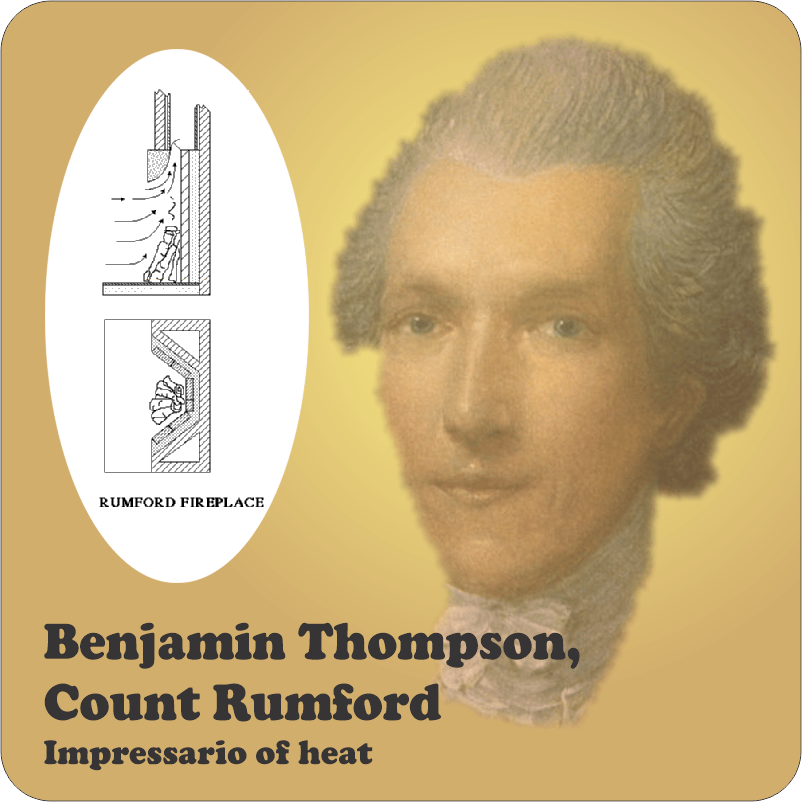

“In later years he became Count Rumford. One of those people who get itchy if they’re not creating something. He was particularly interested in heat — how to trap it and how to make it go where you want.”

“Wait, he was an American but he was a Count? I thought that was illegal.”

“Oh, he left the States before they were the States. During the Revolution he organized a Royalist militia in New York and then lit out for Europe. The Bavarians made him a Count after he spent half‑a‑dozen years doing creative things like reorganizing their army, building public works and introducing potato farming. He concocted a nourishing soup for the poor and invented the soup line for serving it up. But all this time his mind was on a then‑central topic of Physics — what is heat?”

“That was the late 1700s? When everyone said heat was some sort of fluid they called ‘caloric‘?”

“Not everyone, and in fact there were competing theories about caloric — an early version of the particle‑versus‑wave controversy. For a while Rumford even supported the notion that ‘frigorific’ radiation transmitted cold the same way that caloric rays transmitted heat. Whatever, his important contributions were more practical and experimental than theoretical. His redesign of the common fireplace was such an improvement that it took first England and then Europe by storm. Long‑term, though, we remember him for a side observation that he didn’t think important enough to measure properly.”

“Something to do with heat, I’ll bet.”

“Of course. As a wave theory guy, Rumford stood firmly against the ‘caloric is a fluid‘ camp. ‘If heat is material,‘ he reasoned, ‘then a heat‑generating process must eventually run out of caloric.’ He challenged that notion by drilling out a cannon barrel while it was immersed in cold water. A couple of hours of steady grinding brought the water up to boiling. The heating was steady, too, and apparently ‘inexhaustible.’ Better yet, the initial barrel, the cleaned‑out barrel and the drilled‑out shavings all had the same specific heat so no heat had been extracted from anything. He concluded that heat is an aspect of motion, totally contradicting the leading caloric theories and what was left of phlogiston.”

<chuckle> “He was a revolutionary, after all. But what about ‘Enthalpy‘?”

“Here’s an example. Suppose you’ve got a puddle of gasoline, but its temperature is zero kelvins and somehow it’s compressed to zero volume. Add energy to those waggling molecules until the puddle’s at room temperature. Next, push enough atmosphere out of the way to let the puddle expand to its normal size. Pushing the atmosphere takes energy, too — the physicists call that ‘PV work‘ because it’s calculated as the pressure times the volume. The puddle’s enthalpy is its total energy content — thermal plus PV plus the chemical energy you get when it burns.”

~~ Rich Olcott