Cal brings out a fresh batch of scones. He’s tonging them onto the racks when I suddenly get a whiff of mocha latte. I glance back and there’s Susan Kim, grinning at me. “Hi, Sy. Grab your scone and a table. I have a bone to pick with you.”

A few moments later we’re seated. Cal’s coffee’s especially smooth today. “Okay, what’s the bone?”

“You’re playing fast and loose with your enthalpy definition. Yes, there’s change in temperature times entropy, enthalpy’s thermal component, and an expansion‑contraction component you called pressure‑volume. But it’s just sloppy to call what’s left ‘the chemical portion.’ What it is, really, is the combination of every other kind of energy something has that some process could extract. Chemical reactions are just one piece.”

“Strong words, coming from a chemist. What else should be packed in there?”

“Radioactivity, for one. It’s a heat source that doesn’t depend on chemical reactions. Atom for atom, a nuclear disintegration can yield millions of times more energy than a chemical reaction does. Trouble is, radioactive atoms only break down when they feel like it so the energy’s all random heat. I’m sure there’s a bunch of other non‑chemical ways to increase something’s apparent enthalpy.”

“Hmm. Challenge accepted. … It’s all about which process will extract some kind of energy from your something. How about the something’s a tightly‑wound spring? No, wait, that’s chemical, because the energy’s stored in stretched metal‑metal bonds.”

“No, I’ll accept spring tension because there’s no change in chemical composition during the unwind process. What’s another one?”

“Ah. Easy. Kinetic energy if the something’s flying through the air to hit something else.”

“Now you’re cooking. Gravitational potential energy if it’s falling down. Oh, suppose it’s magnetized and goes through a conductive loop on the way down?”

“Nope, doesn’t count. The object’s kinetic energy would produce a jolt of electrical potential in the loop, but it’s own magnetization wouldn’t change. Nice, that distinction sharpens the point — what you count as enthalpy’s third component depends on which change process you’re talking about. If there’s no chemical change, then the chemical part of the internal component of the enthalpy change is zero. In the early days of thermodynamics, for instance, everyone was working on steam. Water may corrode your equipment over the long term, but otherwise it’s just hot water molecules becoming not‑as‑hot water molecules and there’s no change in internal energy. The only energy terms you have to think about are pressure‑volume and temperature‑entropy. That’s why they defined it that way.”

“Which one wins?”

“Hmm?”

“You’ve pared enthalpy changes down to just two kinds of energy. I’ve got to wonder, which one has the bigger contribution?”

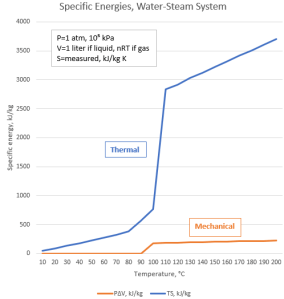

<pulls up a display on Old Reliable> “This is just for the water‑steam system, mind you. Vinnie was surprised. It’s all based on specific heat measurements so visualize one kilogram of liquid water.”

“A liter, right.”

“The line labeled ‘Mechanical’ is the amount of energy you’d get by expanding that kilogram from 0°C up to the temperatures laid out on the x‑axis. No significant expansion up near boiling temperature, then it follows the Ideal Gas Law, PV=nRT. At atmospheric pressure and in this temperature range the expansion relative to 0°C runs about 200 kilojoules per kilogram.”

“And the ‘Thermal’ line?”

“That’s lab‑measured heat capacity values I pulled from the CRC Handbook, each multiplied by the corresponding temperature in kelvins. That’s the amount of energy our kilogram of water molecules holds just by being at the temperature it’s at. The gas makes a nice straight line, at least in the range before heat shatters the molecules.”

“That’s what, fifteen or sixteen times more energy than the mechanical part? Wow! You know, back in Physical Chemistry class they just threw around lots of confusing thermodynamics formulas but never put numbers to them. I had no idea the entropy effect could just swamp whatever else.”

“Numbers do make a difference.”

“This clarifies something I didn’t understand back then. Entropy’s about randomness, right, and a gas molecule can be in more locations in a large volume than in a small one. V=nRT/P says volume rises linearly with temperature and that’s the linear rise in your chart.”

~ Rich Olcott