“Okay, so the yellow part of your graph is molten iron and sulfur, Kareem. What’s with all the complicated stuff going on in the bottom half?”

“It’s not a graph, Cal, it’s a phase diagram. Mmm… what do you think a phase is?”

“What we learned in school — solid, liquid, gas.”

“Sorry, no. Those are states of matter. Water can be in the solid state, that’s ice, or in the liquid state like in my coffee cup here, or in the gaseous state, that’d be water vapor. Phase is a tighter notion. By definition, it’s an instance of matter in a particular state where the same chemical and physical properties hold at every point. Diamond and graphite, for example, are two different phases of solid carbon.”

“Like when Superman squeezes a lump of coal into a diamond?”

“Mm-hm. Come to think of it, Cal, have you ever wondered why the diamonds come out as faceted gems instead of a mold of the inside of his fist? But you’ve got the idea — same material, both in the solid state but in different phases. Anyway, in this diagram each bordered region represents a phase.”

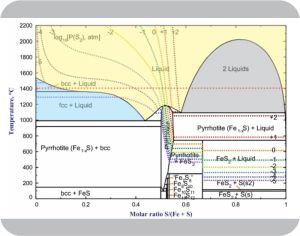

Adapted from Walder and Pelton

“It’s more complicated that that, Kareem. If you look close, each region is actually a mixture of phases. The blue region, for instance, has parts labeled ‘bcc+Liquid’ and ‘fcc+Liquid’. Both ‘bcc’ and ‘fcc’ are crystalline forms of pure iron. Each blue region is really a slush of iron crystals floating in a melt with just enough sulfur to make up the indicated sulfur:iron composition. That line at 1380°C separates conditions where you have one 2‑phase mix or the other.”

“Point taken, Susan. Face it, if region’s not just a straight vertical line then it must enclose a range of compositions. If it’s not strictly molten it must be some mix of at least two separate more‑or‑less pure components. That cool‑temperature mess around 50:50 composition is a jumble when you look at micro sections of a sample that didn’t cool perfectly and they never can. The diagram’s a high‑level look at equilibrium behaviors.”

“Equilibrium?”

“‘Equi–librium’ came from the Latin ‘equal weight’ for a two-pan balance when the beam was perfectly level. The chemists abstracted the idea to refer to a reaction going both ways at the same rate.”

“Can it do that, Susan?”

“Many can, Cal. Say you’ve got a beaker holding some dilute acetic acid and you bubble in some ammonia gas. The two react to produce ammonium ions and acetate ions. But the reaction doesn’t go all the way. Sometimes an ammonium ion and an acetate ion react to produce ammonia and acetic acid. We write the equation with a double arrow to show both directions. Sooner or later you get equally many molecules reacting in each direction and that’s a chemical equilibrium. It looks like nothing’s changing in there but actually a lot’s going on at the molecular level. Given the reactant and product enthalpies Sy’s been banging on about, we can predict how much of each substance will be in the reaction vessel when things settle down.”

“Banging on, indeed. You’re disrespecting a major triumph of 19th‑Century science. Before Gibbs and Helmholtz, industrial chemists had to depend on rules of thumb to figure reaction yields. Now they just look up the enthalpies and they’ can make good estimates. Gibbs even came up with his famous phase rule.”

“You’re gonna tell us, right?”

“Try to stop him.”

“The Gibbs Rule applies to systems in equilibrium where there’s nothing going on that’s biological or involves electromagnetic or gravitational work. Under those restrictions, there’s a limit to how things can vary. According to the rule, a system’s degrees of freedom equals the number of chemical components, minus the number of phases, plus 2. In each blue range, for instance, iron and sulfur make 2 components, minus 2 phases, plus 2, that’s 2 degrees of freedom.”

“So?”

“Composition, temperature and pressure are three intensive variables that you might vary in an experiment. Pick any two, the third is locked in by thermodynamics. Set temperature and pressure, thermodynamics sets the composition.”

~ Rich Olcott