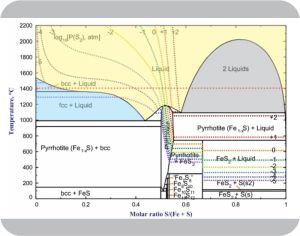

Vinnie pulls a chair over to our table, grabs some paper napkins for scribbling. “You guys know I hate equations, but this Phase Rule one is simple enough even I can play. It says ‘degrees of freedom’ equals ‘components’ minus ‘phases’ plus 2, right? Kareem’s phase diagram has a blue piece with a slush of iron crystals floating in an iron‑sulfur melt. There’s two components, iron and sulfur, two phases, crystals and melt, so the degrees come to 2–2+2=2 and that means we get to choose any two, you said intensive properties, to change. Do I got all that straight, tell me more about degrees and what’s intensive?”

Adapted from Walder and Pelton

Click image to expand

“Good job, Vinnie, and good questions. Extensive properties are about how much. In Kareem’s experiment, he’s free to add iron or sulfur in whatever quantities he wants. By contrast, intensive properties don’t care about how much is there. The equilibrium melt’s iron:sulfur ratio stays between zero and one whatever the size of Kareem’s experiment. The ratio’s an intensive property. So are temperature and pressure. If he kept his experimental pressure constant but raised the temperature, I expect some of the crystals would dissolve. That’d lift the iron:sulfur ratio.”

“How about raising the pressure, Kareem?”

“I suspect that’d squeeze iron back into the crystalline mass, but I’ve not tried that so I don’t know. Different materials behave different ways. Raising the pressure on normal water ice melts it, which is why ice skates work.”

Susan suddenly pulls her tablet from her purse and starts fiddling with it.

“Fair enough. Okay, in your diagram’s top yellow piece where it’s all molten, there’s still 2 components but one phase so the Rule goes 2–1+2=3. You’re saying 3 degrees means you can choose whatever temperature, pressure and mix ratio you want and it’d still be molten.”

“You’ve got the idea, Vinnie. What I’m really interested in, though, is what happens when I add more components. To model Io’s lava pools I need to roll in oxygen and silicon from the surrounding rocks. I’m looking at a 4‑component situation which could have multiple phases and things are complicated”

Vinnie’s got that ‘gotcha’ glint in his eye. “Understood. But how about going in the other direction? If you’ve got only one component then you could have either 1–2+2=1 or 1–3+2=0. How do either of those make sense?”

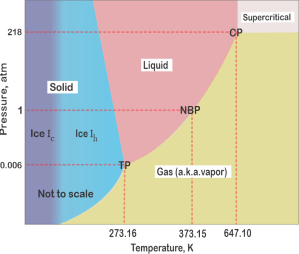

Susan shows a display on her tablet. “As soon as Kareem mentioned ice I figured this phase diagram would come in handy. It’s for water — single component so there’s no variation along a component axis, just pressure and temperature.”

“Kareem had to read his chart to us. Now it’s your turn.”

“Of course. By convention, pressure’s on the y‑axis, temperature’s along the x‑axis. The pressure range is so wide that this chart uses a logarithmic scale which is why the distances look weird. Over there on the cold side, there’s two kinds of ice. Ice Ic has a cubic crystal structure. Warm it up past 240K and it converts to a hexagonal form, Ice Ih. That’s the usual variety that makes snowflakes.”

“TP!” <snirk, snirk>

“Cal, please. That’s water’s Triple Point, Vinnie’s 1–3+2=0 situation where all three phases are in equilibrium with each other so there’s no degrees of freedom. The solid‑liquid and liquid‑vapor boundaries are examples of Vinnie’s 1–2+2=1 condition — only one degree of freedom, which means that equilibrium temperature and pressure are tightly linked together. Squeeze on ice, its melting point drops, so we ice skate on a thin film of liquid water. Normal Boiling Point holds at standard atmospheric pressure but if you heat water while up on a balloon ride it may not get hot enough to hard‑boil those eggs you brought for the picnic.”

“What’s going on in the gray northeast corner?”

“CP‘s the Critical Point at the end of the 1–2+2=1 line. The liquid-vapor surface disappears. No gas or liquid in the container, just opalescent supercritical fog. There’s only one phase; temperature and pressure are independent. Beyond CP you’re in 1–1+2=2 territory.”

~ Rich Olcott