The thing about Vinnie is, he’s always looking for the edges and loopholes. He’d make a good scientist or lawyer but he’s happy flying airplanes. “Guys, I heard a lot of dodging when you started talking about that Gibbs Rule. You said it only works when things are in equilibrium. That’s what Susan was talking about when she said Loki Lake on Io ain’t an equilibrium ’cause there’s stuff getting pumped in and going away so the equations don’t balance. I got that. But then you threw in some other excepts, like no biology or other kinds of work. What’s all that got to do with the phases and chemistry?”

“They’re different processes that drive a system away from equilibrium. Biology, for example. Every kind of life taps energy sources to maintain unstable structures. Proteins, for instance — chemically they’re totally unstable. Oxidation, random acid‑base reactions, lots of ways to degrade a protein molecule’s structure until its atoms wind up in carbon dioxide and nitrogen gas. Your cells, though, they continually burn your food for energy to protect old protein molecules or build new ones and DNA and bones and everything. I visualize someone riding a bicycle up a hillside of falling bowling balls, desperately fighting entropy just to keep upright.”

“Fearsome image, Susan, but it fits. From a Physics perspective, dumping in or extracting any kind of work disrupts any system that’s at equilibrium. The Phase Rule accounts for pressure-volume energy because that’s already part of enthalpy—”

“Wait, Sy, I don’t see pressure‑volume or even ‘PV‘ in

’degrees of freedom=components–phases+2‘.”

“That’s what the ‘2′ is about, Vinnie. If it weren’t for pressure‑volume energy, that two would be a one.”

“C’mon.”

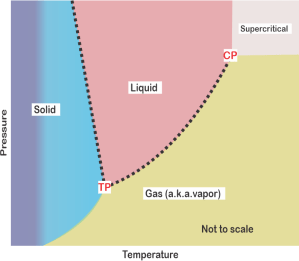

“No, really. ‘Degrees of freedom’ counts the number of intensive properties that are independent of each other. Neither temperature nor pressure care about how much of something you’ve got, so they’re both intensive properties. Temperature’s always there so that’s one degree of freedom. If PV energy’s part of whatever process you’re looking at, then pressure comes into the Rule by way of the enthalpies we use to calculate equilibrium situations. I guess you could write the Rule as

DF=C–P+1T+1PV.“

“That’s not the way we learned that in school, Sy. It was

DF=C–P+1+N,

with ‘N’ counting the number of work modes — PV, gravitational, electrical, whatever fits the problem.”

“How would you do gravitational work on an ice cube, Kareem?”

“Wouldn’t be a cube, Vinnie, it’d be a parcel of Jupiter’s atmosphere caught in a kilometers‑high vertical windstream. Water ice, ammonia ice, ammonium polysulfide solids, all in a hydrogen‑helium medium. A complicated problem; whoever picks it up will have to account for gravity and pressure effects.”

“Come to think of it, the electric option is getting popular and Kareem’s iron‑sulfur system may be a big player. My Chemistry journals have carried a sudden flurry of papers about iron‑sulfur batteries as cheap, safe alternatives to lithium‑based designs for industry‑sized storage where low weight isn’t a consideration. Battery voltage is intensive, doesn’t care about size. Volt’s extensive ‘how much’ buddy is amps. Electrical work is volts times amps so it fits right in with the Rule if I write

DF=C–P+1T+1PV+1VA

A voltage box with sulfur electrodes on one side and iron electrodes on the other would be way out of equilibrium.”

“But why components minus phases? Why not times? What if it comes out negative? What’d that even mean?”

“Fair questions, Vinnie. Degrees of freedom counts independent properties, right? You’d think the phases‑components contribution to DF would be P*C but no. The component percentages in C must total 100%. If you know all but one percentage, the last percentage isn’t independent. Same logic applies to the P phases. That leaves (C–1) and (P–1) independent variables. For the P phases P*C drops to P*(C–1) variables. But you also know that each component is in equilibrium across all phases. Each equilibrium reduces the count by one, for C*(P–1) reductions. Do the subtraction

P*(C–1)–C*(P–1)=C–P

You’re left with only C–P quantities that can change without affecting other things. If the result’s negative it’ll constrain exactly that many other intensive variables, like with water’s triple point.”

~ Rich Olcott