<chirp, chirp> “Excuse me, folks, it’s my niece. Hello, Teena.”

“Hi, Uncle Sy. What’s a kme?”

“Sorry, I don’t know that word. Spell it.”

“I’ve never seen it written down. Brian says the Sun’s specially active and gonna spit out a kme that’ll bang into Earth and knock us out of our orbit.”

“Ah, that’s a C‑M‑E, three separate letters. It stands for Coronal Mass Ejection. As usual, Brian’s got some of it right and much of it wrong. The right part is that the Sun’s at the peak of its 11‑year activity cycle so there’s lots of sunspots and flares—”

“He said flares, too. They’re super bright and could cook an Astronaut and it’d happen so fast we won’t have any warning.”

“Once again, partially right but mostly wrong. Here, let me give you to Cathleen who can set you straight. Cathleen, did you catch the conversation’s drift?”

<phone‑pass pause> “Hello, Teena. I gather you’re upset about solar activity?”

“Hi, Dr O’Meara. Yes, my sorta‑friend Brian likes to scare me with what he brings back from going down YouTube rabbit holes. I don’t really believe him but. You know?”

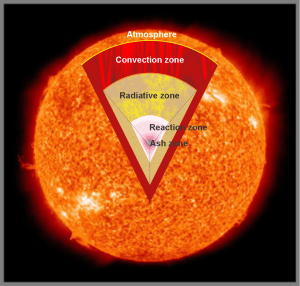

“I understand. Rabbit holes do tend to collect rubbish. Here, let me send you a diagram I use in my classes.” <another pause> “Did you get that?”

“Mm‑hm. Brian showed me a picture like that without the cut‑out part because he was all about the bright flashes.”

“Of course he was. I’ll skip the details, but the idea is that the Sun generates its heat and light energy deep in the reaction zone. Various processes carry that energy up through other zones until it hits the Sun’s atmosphere. You’ve watched water boil on the stove, surely.”

“Oh, yes. Mom put me in charge of doing the pasta last year. I don’t care what they say, a watched pot does eventually boil if there’s enough heat underneath it. I experimented.”

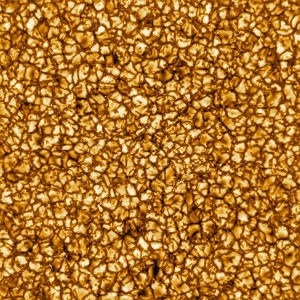

“Wonderful. That process, heat rising into a fluid layer, works the same way on the Sun as it does in your pasta pot. Heat ascends through the fluid but it doesn’t do that uniformly. No, the continuous fluid separates into distinct cells, they’re called Bénard cells, where hot fluid comes up the center, spreads out and cools across the top and then flows down the cell’s outer boundary.”

“That’s what I see happen in the pot with low water and low heat just before the bubbling starts.”

Credit: NSO/AURA/NSF, under CC A4.0 Intl license.

“Right, bubbling will disturb what had been a stable pattern. The cells in the Sun’s surface, they’re called granules, continually rise up to the surface and crowd out neighbors that have cooled off enough to sink or disappear.”

“Funny to say something on the Sun is cool.”

“Relatively cool, only 4000K compared to 6000K. But the Sun has bubbles, too. The granules run about 1500 kilometers wide and last only a quarter‑hour. There’s evidence they’re in top of a supporting layer of supergranules 20 times wider. Or maybe the plasma’s magnetic field is patchy. Anyhow, the surface motion is chaotic. Occasionally, especially concentrated heat or magnetic structure punches out between the granules. There’s a sudden huge release of superhot plasma, a blast of electromagnetic energy radiating out at all frequencies — that’s one of Brian’s flares. Lasts about as long as the granules.”

“That’s what could cook an astronaut?”

“Not really, The radiation’s pretty spread out by the time it’s travelled 150 million kilometers to us. The real danger is from high‑energy particle storms that travel along the Sun’s magnetic field lines. Space crews need to take shelter from them but particle masses travel slower than light so there’s several hours notice.”

“So what about the CMEs?”

“They’re big bubbles of plasma mass that the Sun throws off a few times a year on average. Maybe they come from ultra‑flares but we just don’t know. Their charged particles and magnetic fields can mess up our electronic stuff, but don’t worry about their mass. If a CME’s entire mass hit us straight on, it’d be only a millionth of a millionth of Earth’s mass. We’d roll on just fine.”

~ Rich Olcott