Kareem puts in another couple of chips. “Hold your horses, Cal. The conversation‘s just getting interesting.”

Vinnie raises him a few chips. “Hey, Mr Geology. Just how rare are these lanthanide rare earths? And if they’re metals, how come they’re called earths?”

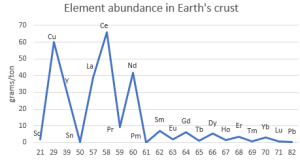

“Not that rare.” <pulls up an image on his phone> “Here’s a quick abundance chart for the lanthanides and a few other elements averaged over all of Earth’s continental crust. Cerium’s more abundant than copper and 350 times more common than lead. Of course, that’s an average. Lanthanide concentrations in economically viable ores are much higher, just like with copper, lead, tin and other important non‑ferrous metals.”

“Funny zig-zag pattern there.”

“Good catch, Cal. Even‑number elements are generally more abundant than their odd‑numbered neighbors. That’s the Oddo-Harkins Rule in action—”

“ODDo-Harkins, haw!”

“You’re—” <Susan’s catches Vinnie’s frown and quickly drops few chips onto the pile> “Sorry, Vinnie. You’re not the first person to flag that pun. Two meteorite chemists named Giuseppe Oddo and William Harkins developed the rule a century ago. We’re pretty sure the pattern has to do with how stars fuse even‑numbered alpha particles to build up the elements heavier than hydrogen and helium. As to why the rare earths are called earths, back when Chemistry was just splitting away from alchemy, an ‘earth‘ was any crumbly mineral. Anybody heard of diatomaceous earth?”

Cal perks up. “Yeah, I got a bag of that dust in my garden shed to kill off slugs.”

“Mm‑hm. Powdery, mostly silica with some clay and iron oxide. The original ‘earth’ definition eventually morphed to denote minerals that dissolve in acid” <grin> “which diatomaceous earth doesn’t do. A few favorable Scandinavian mines gave the Swedish chemists lanthanide‑enriched ores to work on. Strictly speaking, in metallic form the lanthanides are rare earth metals, not rare earths, but people get sloppy.”

Eddie pitches in some chips. “So they’re <snort> chemical odd‑ities. Why would anyone but a chemist care about them?”

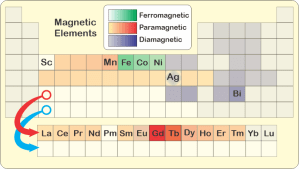

<sigh> “Magnetism.” <shows her laptop’s screen> “Here’s a chart that highlights the elements that are most magnetically active. The lanthanides are that colored strip below the main table. Chemically they’d all fit into that box with the red circle. They’re—”

“Wait, there’s more than one kind of magnetism?”

“Oh, yes. The distinction’s about how an element or material interacts with an external magnetic field. Most elements are at least weakly paramagnetic, which means they’re pulled into the field; diamagnets push away from it. Diamagnetic reaction is generally far weaker. Manganese is the strongest paramagnet, about 70 times stronger per atom than the strongest diamagnet, bismuth. Then there’s iron, cobalt and nickel — they do ferromagnetism, which means their atoms interact so strongly with the field that they get their neighbors to join in and make a permanent magnet.”

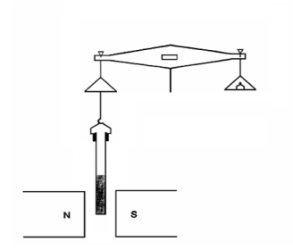

“How does anyone find out whether the field’s pulling or pushing?”

“Good question, Cal (you owe the pot, by the way). Basically, the idea is to somehow weigh a sample both with and without a surrounding field. Tammy’s lab down the hall from me has a nice Gouy Balance setup which is one way to make that measurement. The balance stands on a counter over a hole that leads down to a hollow glass tube that guards against air currents. There’s also a big powerful permanent magnet down there, mounted on a hinged arrangement. Your sample hangs on a piece of fishline hooked to the balance pan. Take a weight reading, swing the magnet into position just below the sample, read the weight again, do some arithmetic and you’re done. A higher weight reading when the field’s in place means your sample’s paramagnetic, less weight means it’s diamagnetic.”

“Why does that Ag box look weird in your table, sort of half‑brown and half‑gray?”

“That’s silver, Eddie. It’s an edge case. The pure metal’s diamagnetic but alloy a sample with even a small fraction of some ferromagnetic atoms and you’ve made it paramagnetic. Magnetism’s one test that people in the silver trade use to check if a coin or bar is pure. How that works isn’t my field. Sy, it’s your turn to bet and explain.”

~ Rich Olcott