Late Summer is quiet time on campus and in my office. Too quiet. I head over to Cal’s coffee shop in search of company. “Morning, Cal.”

“Morning, Sy. Sure am glad to see you. There’s no‑one else around.”

“So I see. No scones in the rack?”

“Not enough traffic yet to justify firing up the oven on such a hot day. How about a biscotti instead?”

“If it’s only the one it’s a biscotto. Pizza Eddie’s very firm on that. Yeah, I’ll have one.”

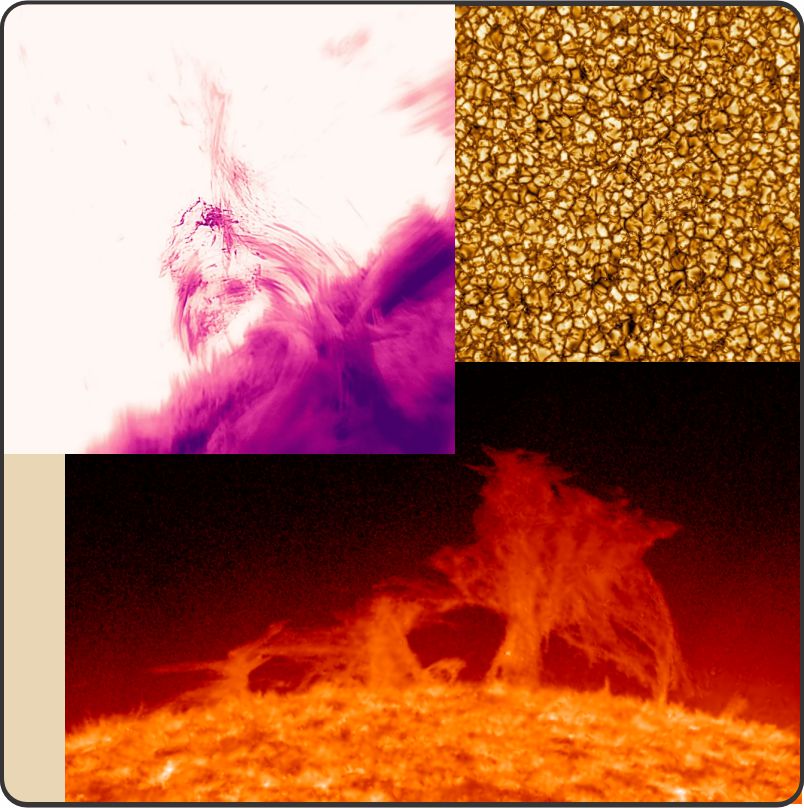

“Always learning. By the way, a photo spread in one of my astronomy magazines got me thinking. How come there’s so much flat out there?”

“Huh? I know you’re not one of those flat‑Earthers.”

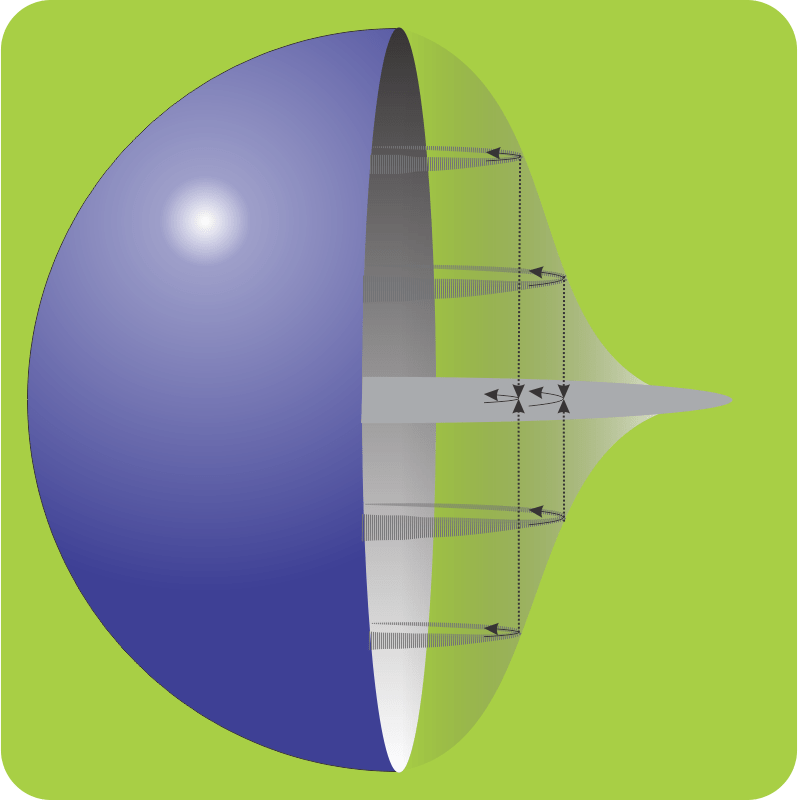

“Not the planets, I mean the way their orbits go all in the same plane. Same for most of the asteroids and the Kuiper belt, even. Our Milky Way galaxy’s basically flat, too, and so are a lot of the others. Black hole accretion disks are flat. You’d think if some baby star or galaxy was attracting stuff from everywhere to grow itself, the incoming would make a big globe. But it’s not, we get flatness. How come?”

“Bad aim and angular momentum.”

“What’s aim got to do with it?”

“Suppose there’s only two objects in the Universe and they’re closing in on each other. If they’re aimed dead‑center to each other, what happens?”

“CaaaRUNCH!!!”

“Right. Now what if the aim’s off so they don’t quite touch?”

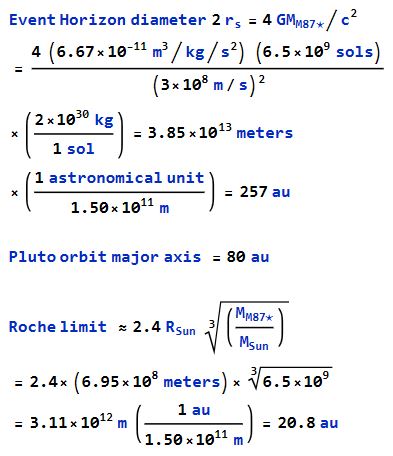

“Oh, I know that one … it’ll come to me … yeah, Roche’s limit, it was in an article a few months ago. Whichever’s less dense will break up and all the pieces go like Saturn’s rings. Which are also flat, by the way.”

“In orbit around the survivor, mm‑hm. The pieces can’t fall straight down because they still have angular momentum.”

“I know about momentum like when you crash a car if you go too fast for your brakes. Heavier car or faster speed, you get a worse crash. How does angle fit into that — bigger angle, more angular momentum?”

“Not quite. In general, momentum is mass multiplied by speed. It’s a measure of the force required to stop something or at least slow it down. You’ve described linear momentum, where ‘speed’ is straight‑line distance per time. If you’re moving along a curve, ‘speed’ is arc‑length per time.”

“Arc‑length?”

“Distance around part of a circle. Arc‑length is angle in radians, multiplied by the circle’s radius. If you zip halfway around a big circle in the same time it took me to go halfway around a small circle, you’ve got more angular momentum than I do and it’d take more force to stop you. Make sense?”

“What if it’s not a circle? The planet orbits are all ellipses.”

“It’s still arc‑length except that you need calculus to figure it. That’s why Newton and Leibniz invented their methods. A falling something that misses a gravity center keeps falling but on an orbit. Whatever momentum it has acts as angular momentum relative to that center. There’s no falling any further in without banging into something else coming the other way and each object canceling the other’s momentum.”

“Or burning fuel if it’s a spaceship.”

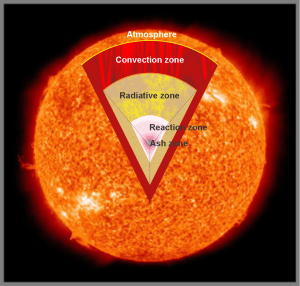

“… Right. … So anyway, suppose you’ve got a star or something initially surrounded by a spherical cloud of space junk whirling around in all different orbits. What’s going to happen?”

“Lots of banging and momentum canceling until everything’s swirling more‑or‑less in the same direction and closer in than at come‑together time. But it’s still a ball.”

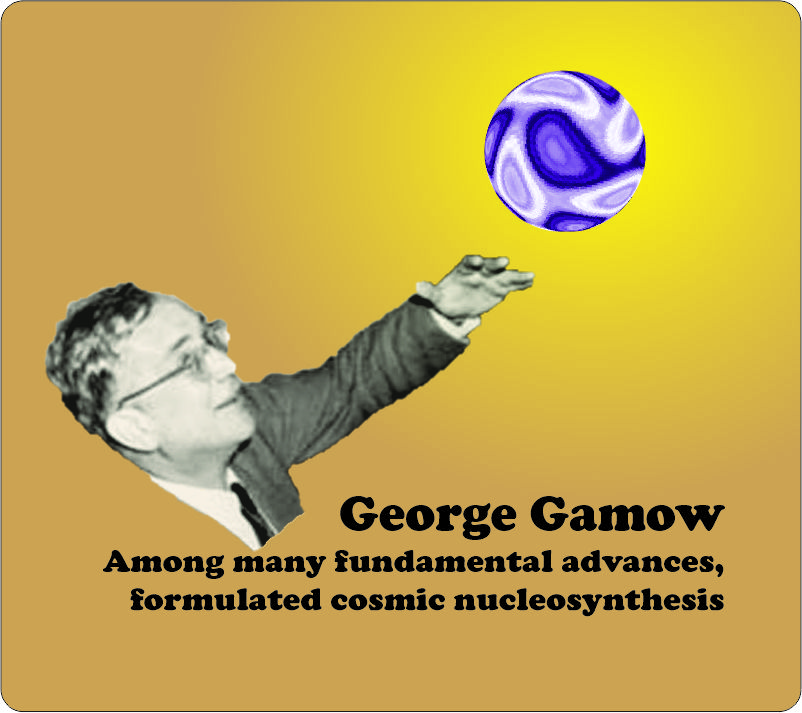

“Gravity’s not done. Think about northern debris. It’s attracted to the center, but it’s also attracted to the southern debris and vice-versa. They’ll meet midway and build a disk. The ball‑to‑disk collapse isn’t even opposed by angular momentum. Material at high latitudes, north and south, can lose gravitational potential energy by dropping straight in toward the equator and still be at the orbitally correct distance from the axis of rotation.”

“That’d work for stuff collecting around a planet, wouldn’t it?”

“It’d even work for stuff collecting around nothing, just a clump in a random density field. That may be how stars are born. Collapsing’s the hard part.”

~ Rich Olcott