Sometimes the media get sloppy. OK, a lot of times, especially when the reporters don’t know what they’re writing about. Despite many headlines that “LIGO detected gravity waves,” that’s just not so. In fact, the LIGO team went to a great deal of trouble to ensure that gravity waves didn’t muck up their search for gravitational waves.

A wave happens in a system when a driving force and a restoring force take turns overshooting an equilibrium point AND the away-from-equilibrium-ness gets communicated around the system. The system could be a bunch of springs tied together in a squeaky old bedframe, or labor and capital in an economic system, or the network of water molecules forming the ocean surface, or the fibers in the fabric of space (whatever those turn out to be).

A wave happens in a system when a driving force and a restoring force take turns overshooting an equilibrium point AND the away-from-equilibrium-ness gets communicated around the system. The system could be a bunch of springs tied together in a squeaky old bedframe, or labor and capital in an economic system, or the network of water molecules forming the ocean surface, or the fibers in the fabric of space (whatever those turn out to be).

If you were to build a mathematical model of some wavery system you’d have to include those two forces plus quantitative descriptions of the thingies that do the moving and communicating. If you don’t add anything else, the model will predict motion that cycles forever. In reality, of course, there’s always something else that lets the system relax into equilibrium.

The something else could be a third force, maybe someone sitting on the bed, or government regulation in an economy, or reactant depletion for a chemical process. But usually it’s friction of one sort or another — friction drains away energy of motion and converts it to heat. Inside a spring, for instance, adjacent crystallites of metal rub against each other. There appears to be very little friction in space — we can see starlight waves that have traveled for billions of years.

Physicists pay attention to waves because there are some general properties that apply to all of them. For instance, in 1743 Jean-Baptiste le Rond d’Alembert proved there’s a strict relationship between a wave’s peakiness and its time behavior. Furthermore, Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier (pre-Revolutionary France must have been hip-deep in physicist-mathematicians) showed that a wide variety of more-or-less periodic phenomena could be modeled as the sum of waves of differing frequency and amplitude.

Monsieur Fourier’s insight has had an immeasurable impact on our daily lives. You can thank him any time you hear the word “frequency.” From broadcast radio and digitally recorded music to time-series-based business forecasting to the mode-locked lasers in a LIGO device — none would exist without Fourier’s reasoning.

Gravity waves happen when a fluid is disturbed and the restoring force is gravity. We’re talking physicist fluid here, which could be sea water or the atmosphere or solar plasma, anything where the constituent particles aren’t locked in place. Winds or mountain slopes or nuclear explosions push the fluid upwards, gravity pulls it back, and things wobble until friction dissipates that energy.

Gravitational waves are wobbles in gravity itself, or rather, wobbles in the shape of space. According to General Relativity, mass exerts a tension-like force that squeezes together the spacetime immediately around it. The more mass, the greater the tension.

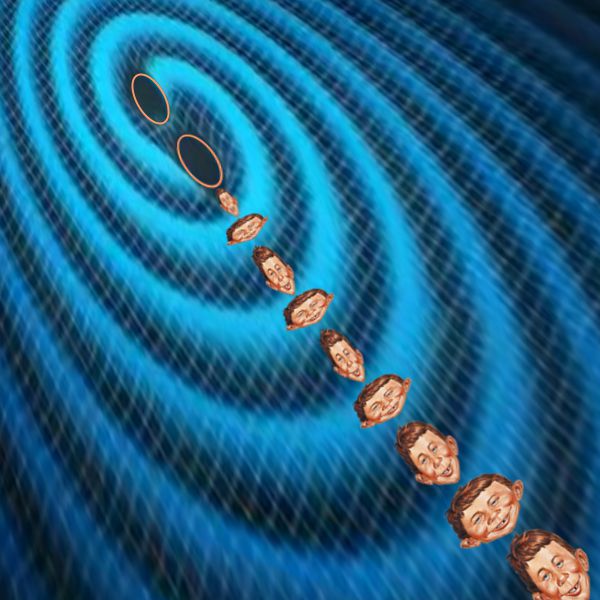

An isolated black hole is surrounded by an intense gravitational field and a corresponding compression of spacetime. A pair of black holes orbiting each other sends out an alternating series of tensions, first high, then extremely high, then high…

An isolated black hole is surrounded by an intense gravitational field and a corresponding compression of spacetime. A pair of black holes orbiting each other sends out an alternating series of tensions, first high, then extremely high, then high…

Along any given direction from the pair you’d feel a pulsing gravitational field that varied above and below the average force attracting you to the pair. From a distance and looking down at the orbital plane, if you could see the shape of space you’d see it was distorted by four interlocking spirals of high and low compression, all steadily expanding at the speed of light.

The LIGO team was very aware that the signal of a gravitational wave could be covered up by interfering signals from gravity waves — ocean tides, Earth tides, atmospheric disturbances, janitorial footsteps, you name it. The design team arrayed each LIGO site with hundreds of “seismometers, accelerometers, microphones, magnetometers, radio receivers, power monitors and a cosmic ray detector.” As the team processed the LIGO trace they accounted for artifacts that could have come from those sources.

So no, the LIGO team didn’t discover gravity waves, we’ve known about them for a century. But they did detect the really interesting other kind.

~~ Rich Olcott

Almost a century later, James Clerk Maxwell (the bearded fellow at left) wrote down his electromagnetism equations that explain how light works. Half a century later, Einstein did the same for gravity.

Almost a century later, James Clerk Maxwell (the bearded fellow at left) wrote down his electromagnetism equations that explain how light works. Half a century later, Einstein did the same for gravity.

Gravitodynamics is completely unlike electrodynamics. Gravity’s transverse “force” doesn’t act to move a whole mass up and down like Maxwell’s picture at left. Instead, as shown by Einstein’s picture, gravitational waves stretch and compress while leaving the center of mass in place. I put “force” in quotes because what’s being stretched and compressed is space itself. See

Gravitodynamics is completely unlike electrodynamics. Gravity’s transverse “force” doesn’t act to move a whole mass up and down like Maxwell’s picture at left. Instead, as shown by Einstein’s picture, gravitational waves stretch and compress while leaving the center of mass in place. I put “force” in quotes because what’s being stretched and compressed is space itself. See

The experiment consists of shooting laser beams out along both arms, then comparing the returned beams.

The experiment consists of shooting laser beams out along both arms, then comparing the returned beams.