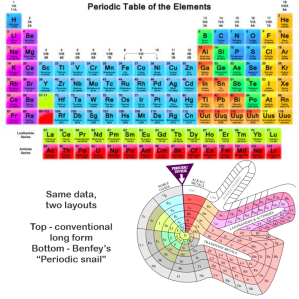

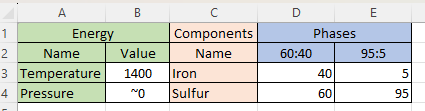

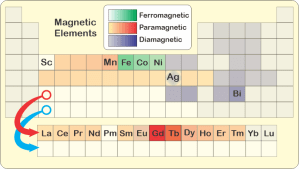

“Why’s the Ag box look weird in your chart, Susan?”

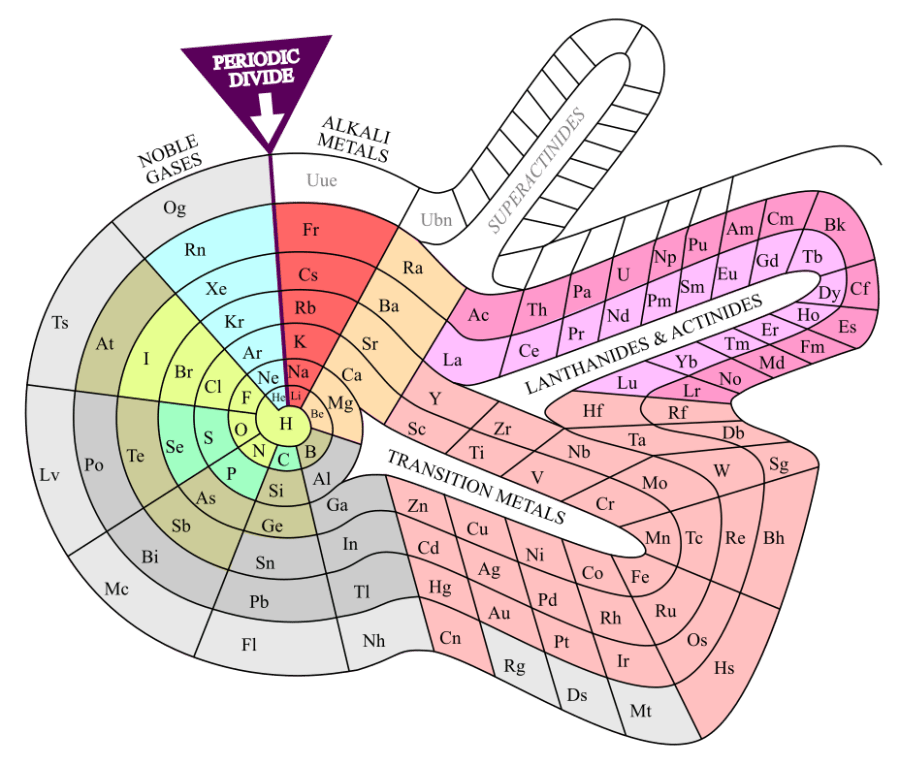

“That’s silver, Eddie. It’s an edge case. The pure metal’s diamagnetic. If you alloy silver with even a small amount of iron, the mixture is paramagnetic. How that works isn’t my field. Sy, it’s your turn to bet and explain.”

I match Eddie’s bet (the hand’s not over). “It’s magnetism and angular momentum and how atoms work, and there are parts I can’t explain. Even Feynman couldn’t explain some of it. Vinnie, what do you remember about electromagnetic waves?”

“Electric part pushes electrons up and down, magnetic part twists ’em sideways.”

“Good enough, but as Newton said, action begets reaction. Two centuries ago, Ørsted discovered that electrons moving along a wire create a magnetic field. Moving charges always do that. The effect doesn’t even depend on wires — auroras, fusion reactor and solar plasmas display all sorts of magnetic phenomena.”

“You said it’s about how atoms work.”

“Yes, I did. Atoms don’t follow Newton’s rules because electrons aren’t bouncing balls like those school‑book pictures show. An electron’s only a particle when it hits something and stops; otherwise it’s a wave. The moving wave carries charge so it generates a magnetic field proportional to the wave’s momentum. With me?”

“Keep going.”

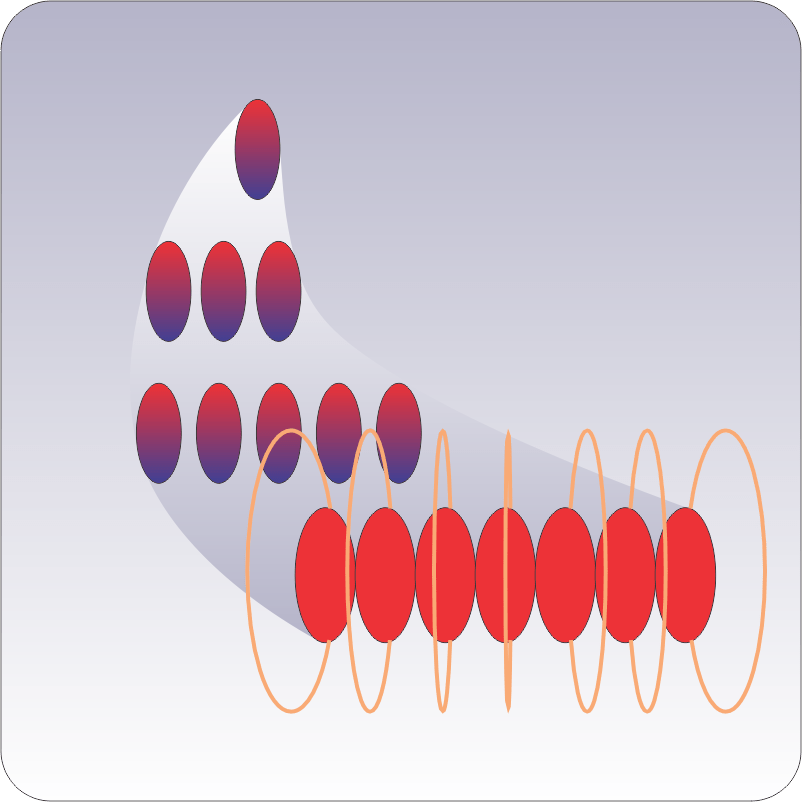

“That picture’s fine for a wave traveling through space, but in an atom all the charge waves circle the nucleus. Linear momentum in open space becomes angular momentum around the core. If every wave in an atom went in the same direction it’d look like an electron donut generating a good strong dipolar magnetic field coming up through the hole.”

“You said ‘if’.”

“Yes, because they don’t do that. I’m way over‑simplifying here but you can think of the waves pairing up, two single‑electron waves going in opposite directions.”

“If they do that, the magnetism cancels.”

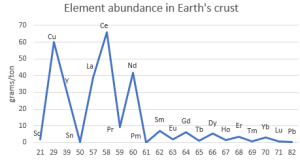

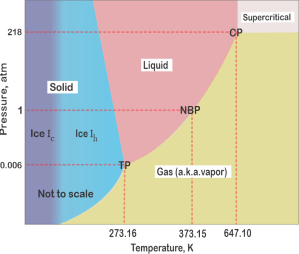

“Mm‑hm. Paired‑up configurations are almost always the energy‑preferred ones. An external magnetic field has trouble penetrating those structures. They push the field away so we classify them as diamagnetic. The gray elements in Susan’s chart are almost exclusively in paired‑up configurations, whether as pure elements or in compounds.”

“Okay, so what about all those paramagnetic elements?”

Credit: Inigo.quilez, under CCA SA 3.0 license

“Here’s where we get into atom structure. An atom’s electron cloud is described by spherical harmonic modes we call orbitals, with different energy levels and different amounts of angular momentum — more complex shapes have more momentum. Any orbital hosting an unpaired charge has uncanceled angular momentum. Two kinds of angular momentum, actually — orbital momentum and spin momentum.”

“Wait, how can a wave spin?”

“Hard to visualize, right? Experiments show that an electron carries a dipolar magnetic field just like a spinning charge nubbin would. That’s the part that Feynman couldn’t explain without math. A charge wave with spin and orbital angular momentum is charge in motion; it generates a magnetic field just like current through a wire does. The math makes good predictions but it’s not something that everyday experience prepares us for. Anyway, the green and yellow‑orange‑ish elements feature unpaired electrons in high‑momentum orbitals buried deep in the atom’s charge cloud.”

“So what?”

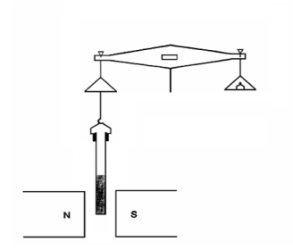

“So when an external magnetic field comes along, the atom’s unpaired electrons join the party. They orient their fields parallel to the external field, in effect allowing it to penetrate. That qualifies the atom as paramagnetic. More unpaired electrons means stronger interaction, which is why iron goes beyond paramagnetic to ferromagnetic.”

“How does iron have so many?”

“Iron’s halfway across its row of ten transition metals—”

“I know where you’re going with this, Sy. It’ll help to say that these elements tend to lose their outer electrons. Scandium over on the left ionizes to Sc3+ and has zero d‑electrons. Then you add one electron in a d orbital for each move to the right.”

“Thanks, Susan. Count ’em off, Vinnie. Five steps over to iron, five added d‑electrons, all unpaired. Gadolinium, down in the lanthanides, beats that with seven half‑filled f‑orbitals. That’s where the strength in rare earth magnets arises.”

“So unpaired electrons from iron flip alloyed silver paramagnetic?”

“Vinnie wins this pot.”

~ Rich Olcott