Vinnie clomps into my office. “Morning, Sy. I knew you weren’t busy ’cause there’s music playing.”

“Well, you’re right, I am between assignments. Yesterday another client called to say they’re cancelling my contract because their Federal grant was cut off. They had to let three grad students go, too. That was a project with good prospects for generating a couple of successful businesses. These zealots are eating our seed corn, Vinnie, and they’re burning down the silo.”

“I know the feeling, Sy. There’s a lot less charter flying to do these days. Nobody wants to do meetings when they don’t know what the rules will be next week.”

<deep sigh>

<deep sigh>

“Oh, yeah, Sy. Why I came up here — what’s with white holes? Cal asked me about ’em ’cause a little squib in one of his astronomy magazines didn’t tell us much so now I’m curious.”

“Okay, tell me something you know about black holes.”

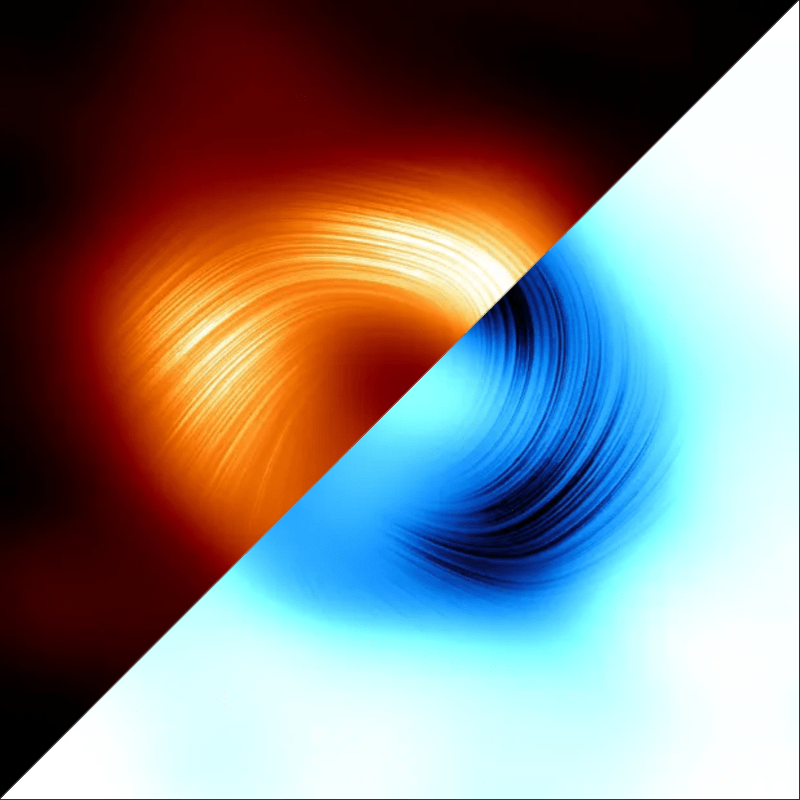

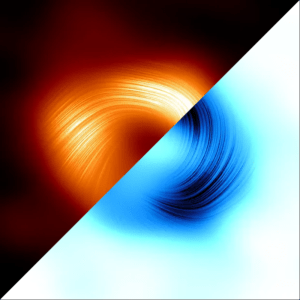

“We can’t see one, but we can see light from its accretion disc.”

“Fair enough. Something else.”

“A black hole’s what you get when a right‑size star collapses.”

“I like that ‘right‑size’ qualification. Too small or too big doesn’t work. White holes almost certainly can’t happen from a star collapse. What else?”

“I heard that ‘almost.’ Uhh… once you pass inside the Event Horizon, you can’t get out.”

“You can’t get inside a white hole’s Event Horizon.”

“Okay, that’s weird. Like it’s got a hard crust like black holes don’t?”

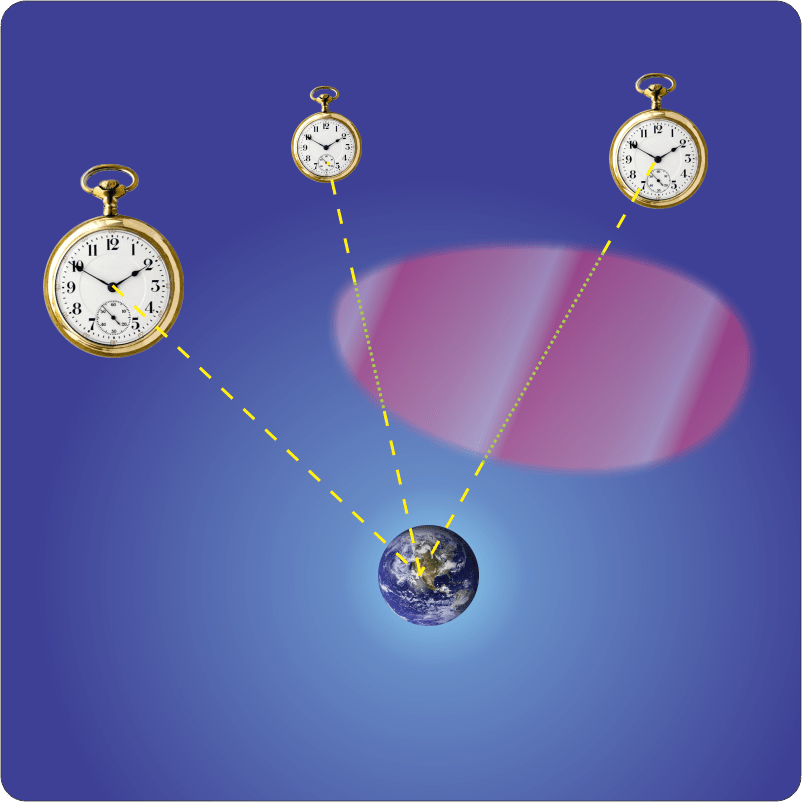

“Nope. A white hole’s Event Horizon’s a mathematical abstraction just like a black hole’s. Not a hard surface, just a boundary where time starts playing games.”

“Wait, we talked about time and the Event Horizon some time ago. If I remember right, we worked out that cause‑and‑effect runs parallel to time. Outside the Event horizon time’s not locked to any specific orientation in space. We can cause things to happen in any direction. Inside the Event Horizon’s sphere, both time and cause‑and‑effect point further in. You can’t make anything happen further out than wherever you are in there which is why light can’t escape, right?”

“Mostly. Anything inside the Horizon is bound to spiral inward toward the singularity. The journey could be slow or fast. There’s some disagreement on how long it would take, though — could be forever, could be forever near enough. Some current models say the Horizon’s geometric center is the infinitely distant future. Other models say, no, for a stellar‑collapse black hole it’s only beyond the age of the Universe.”

“Why not … oh, because the real black hole was born at a definite time so it can’t have an infinite future.”

“That’s about the size of it — both directions either finite or infinite. Physicists love to propose symmetries like that but I’m not willing to bet either way.”

“Black hole/white hole sounds like symmetry.”

“In a way it isn’t, in a way it is. Both varieties are solutions for Einstein’s equation about spacetime under—”

“Hold it, no equations, you know I hate those things. Anyway, how can two different holes solve one equation?”

“Solve x=√9.”

“Gotta be x=3.”

“Or minus‑3. They’re both right answers, right?”

“Mmm, yeah. Okay, that was arithmetic, not an equation, but why’d you give it to me at all?”

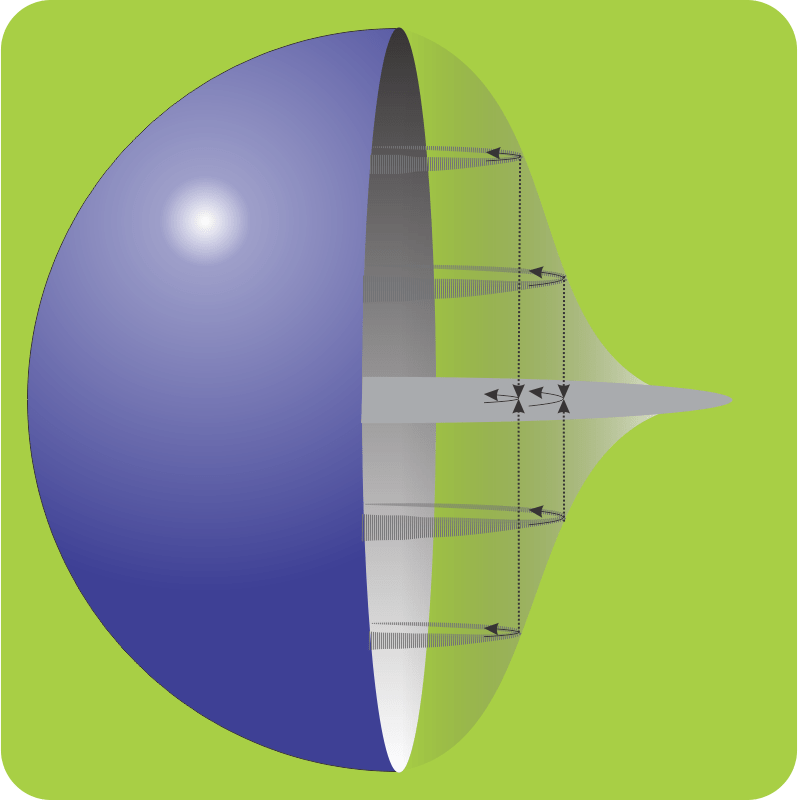

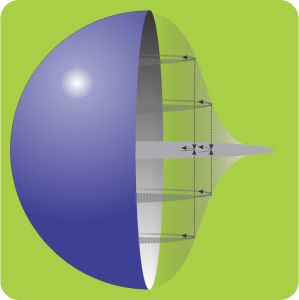

“To demonstrate plus‑or‑minus symmetry. Einstein’s equation tells how mass warps spacetime. The answers relate to square‑roots of summed squares like Pythagoras’ c=√(a²+b²). If you pick positive square roots the warping describes a black hole. The negative square roots give the warping for a white hole which behaves differently. Both kinds depend on intense gravitational fields arising from a singularity but a white hole’s cause‑and‑effect arrow points outward.”

“So that’s why you’re locked out? You can’t cause anything further in than you are?”

“Exactly. But it gets deeper. A black hole’s singularity, the one you can’t avoid if you’re inside its Event Horizon, is in the distant future. A white hole’s singularity, the one you can’t get to anyway, is in the distant past.”

“That’s why you said they can’t come from star collapses — the stars died too recent.”

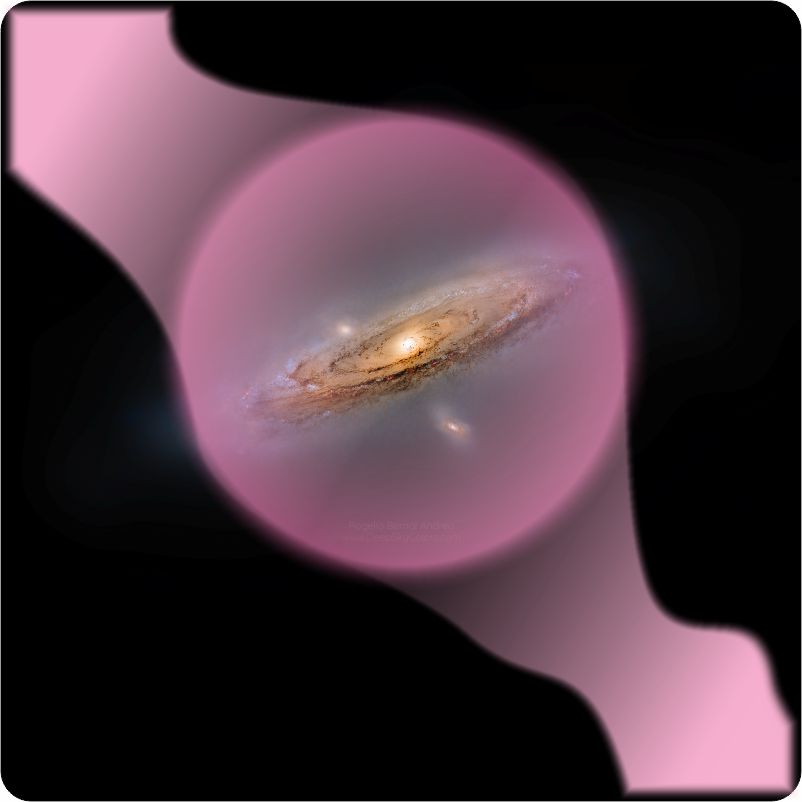

“Mm-hm. If white holes exist at all, they probably were born in the Big Bang.”

~ Rich Olcott