Suddenly there’s a hubbub of girlish voices to one side of the crowd. “Go on, Jeremy, get up there.” “Yeah, Jeremy, your theory’s no crazier than theirs.” “Do it, Jeremy.”

Sure enough, the kid’s here with some of his groupies. Don’t know how he does it. He’s a lot younger than the grad students who generally present at these contests, but he’s got guts and he grabs the mic.

“OK, here’s my Crazy Theory. The Solar System has eight planets going around the Sun, and an oxygen atom has eight electrons going around the nucleus. Maybe we’re living in an oxygen atom in some humongous Universe, and maybe there are people living on the electrons in our oxygen atoms or whatever. Maybe the Galaxy is like some huge molecule. Think about living on an electron in a uranium atom with 91 other planets in the same solar system and what happens when the nucleus fissions. Would that be like a nova?”

There’s a hush because no-one knows where to start, then Cathleen’s voice comes from the back of the room. Of course she’s here — some of the Crazy Theory contest ring-leaders are her Astronomy students. “Congratulations, Jeremy, you’ve joined the Honorable Legion of Planetary Atom Theorists. Is there anyone in the room who hasn’t played with the idea at some time?”

No-one raises a hand except a couple of Jeremy’s groupies.

“See, Jeremy, you’re in good company. But there are a few problems with the idea. I’ll start off with some astronomical issues and then the physicists can throw in some more. First, stars going nova collapse, they don’t fission. Second, compared to the outermost planet in the Solar System, how far is it from the Sun to the nearest star?”

A different groupie raises her hand and a calculator. “Neptune’s about 4 light-hours from the Sun and Alpha Centauri’s a little over 4 light-years, so that would be … the 4’s cancel, 24 hours times 365 … about 8760 times further away than Neptune.”

“Nicely done. That’s a typical star-to-star distance within the disk and away from the central bulge. Now, how far apart are the atoms in a molecule?”

“Aren’t they pretty much touching? That’s a lot closer than 8760 times the distance.”

“Yes, indeed, Jeremy. Anyone else with an objection? Ah, Maria. Go ahead.”

“Yes, ma’am. All electrons have exactly the same properties, ¿yes? but different planets, they have different properties. Jupiter is much, much heavier than Earth or Mercury.”

Astrophysicist-in-training Jim speaks up. “Different force laws. Solar systems are held together by gravity but at this level atoms are held together by electromagnetic forces.”

“Carry that a step further, Jim. What does that say about the geometry?”

“Gravity’s always attractive. The planets are attracted to the Sun but they’re also attracted to each other. That’ll tend to pull them all into the same plane and you’ll get a flat disk, mostly. In an atom, though, the electrons or at least the charge centers repel each other — four starting at the corners of a square would push two out of the plane to form a tetrahedron, and so forth. That’s leaving aside electron spin. Anyhow, the electronic charge will be three-dimensional around the nucleus, not planar. Do you want me to go into what a magnetic field would do?”

“No, I think the point’s been made. Would someone from the Physics side care to chime in?”

“Synchrotron radiation.”

“Good one. And you are …?”

“Newt Barnes. I’m one of Dr Hanneken’s students.”

“Care to explain?”

“Sure. Assume a hydrogen atom is a little solar system with one electron in orbit around the nucleus. Any time a charge moves it radiates waves into the electromagnetic field. The waves carry forces that can compel other charged objects to move. The distance an object moves, times the force exerted, equals the amount of energy expended by the wave. Therefore the wave must carry energy and that energy must have come from the electron’s motion. After a while the electron runs out of kinetic energy and falls into the nucleus. That doesn’t actually happen, so the atom’s not a solar system.”

Jeremy gets general applause when he waves submission, then the crowd’s chant resumes…

.——<“Amanda! Amanda! Amanda!”>

~~ Rich Olcott

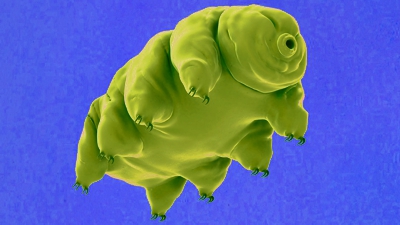

“If they’re so small, why are they called bears?”

“If they’re so small, why are they called bears?” “Yup, and that’s one way astronomers can classify planets. Earth’s in the Goldilocks Zone for liquid water, essential for life as we know it. Saturn’s moon Titan might support some other kind of life in its

“Yup, and that’s one way astronomers can classify planets. Earth’s in the Goldilocks Zone for liquid water, essential for life as we know it. Saturn’s moon Titan might support some other kind of life in its

“That’s what the LaForge Drive does, Mr Moire. The counter-rotating blades are an osmium-

“That’s what the LaForge Drive does, Mr Moire. The counter-rotating blades are an osmium-

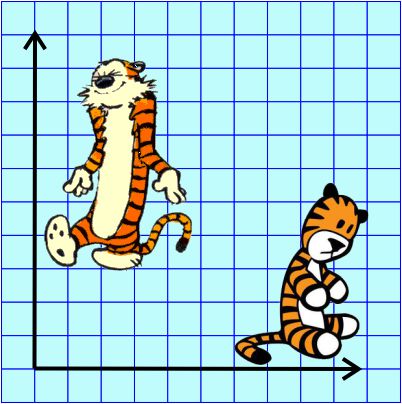

I so miss Calvin and Hobbes, the wondrous, joyful comic strip that cartoonist Bill Watterson gave us between 1985 and 1995. Hobbes was a stuffed toy tiger — except that 6-year-old Calvin saw him as a walking, talking man-sized tiger with a sarcastic sense of humor.

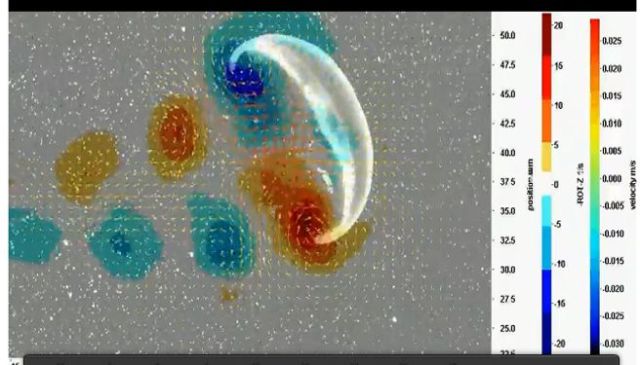

I so miss Calvin and Hobbes, the wondrous, joyful comic strip that cartoonist Bill Watterson gave us between 1985 and 1995. Hobbes was a stuffed toy tiger — except that 6-year-old Calvin saw him as a walking, talking man-sized tiger with a sarcastic sense of humor. In this video, orange, green and blue electromagnetic fields shine in from one side of the box onto its floor. Each color’s field is polar because it “lives” in only one plane. However, the beam as a whole is unpolarized because different components of the total field direct recipient electrons into different planes giving zero net polarization. The Sun and most other familiar light sources emit unpolarized light.

In this video, orange, green and blue electromagnetic fields shine in from one side of the box onto its floor. Each color’s field is polar because it “lives” in only one plane. However, the beam as a whole is unpolarized because different components of the total field direct recipient electrons into different planes giving zero net polarization. The Sun and most other familiar light sources emit unpolarized light.

Suppose you had a graph with one axis for counting animal things and another for counting vegetable things. Animals added to animals makes more animals; vegetables added to vegetables makes more vegetables. If you’ve got a chicken, two potatoes and an onion, and you share with your buddy who has a couple of carrots, some green beans and another onion, you’re on your way to a nice chicken stew.

Suppose you had a graph with one axis for counting animal things and another for counting vegetable things. Animals added to animals makes more animals; vegetables added to vegetables makes more vegetables. If you’ve got a chicken, two potatoes and an onion, and you share with your buddy who has a couple of carrots, some green beans and another onion, you’re on your way to a nice chicken stew.

I was only 10 years old but already had Space Fever thanks to Chesley Bonestell’s artwork in Collier’s and Life magazines. I eagerly joined the the movie theater ticket line to see George Pal’s Destination Moon. I loved the Woody Woodpecker cartoon (it’s 12 minutes into the

I was only 10 years old but already had Space Fever thanks to Chesley Bonestell’s artwork in Collier’s and Life magazines. I eagerly joined the the movie theater ticket line to see George Pal’s Destination Moon. I loved the Woody Woodpecker cartoon (it’s 12 minutes into the

Grammie always grimaced when Grampie lit up one of his cigars inside the house. We kids grinned though because he’d soon be blowing smoke rings for us. Great fun to try poking a finger into the center, but we quickly learned that the ring itself vanished if we touched it.

Grammie always grimaced when Grampie lit up one of his cigars inside the house. We kids grinned though because he’d soon be blowing smoke rings for us. Great fun to try poking a finger into the center, but we quickly learned that the ring itself vanished if we touched it.

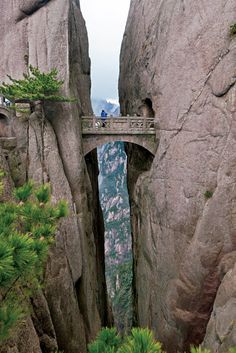

See that little guy on the bridge, suspended halfway between all the way down and all the way up? That’s us on the cosmic size scale.

See that little guy on the bridge, suspended halfway between all the way down and all the way up? That’s us on the cosmic size scale. So that’s the size range of the Universe, from 1.6×10-35 up to 2.6×1026 meters. What’s a reasonable way to fix a half-way mark between them?

So that’s the size range of the Universe, from 1.6×10-35 up to 2.6×1026 meters. What’s a reasonable way to fix a half-way mark between them?