The Klein bottle is one of the most misunderstood objects in popular math. Let’s start with the name. When he initially described the object Herr Doktor Professor Felix Klein said it was a surface. Being German and writing in German, he used the word Fläche (note the two little dots over the a). When his paper was translated to English, the translator noticed the shape of the thing but didn’t notice those two little dots. He misread the word as Flasche, meaning flask or bottle, and the latter word stuck.

So who was Herr Klein and what was it that he wrote about? One of the world’s foremost mathematicians in the last quarter of the 19 Century, he specialized in geometry, complex analysis and mathematical physics. Among his other accomplishments was that as director of a research center at Georg-August-Universität Göttingen in 1895 he supervised Germany’s first Ph.D. thesis written by a woman (Grace Chisholm Young).

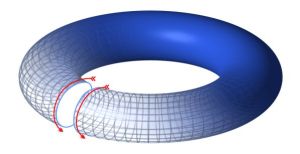

As a small part of one of his many papers he noted that a cylinder could be deformed in two different ways to connect its two ends. The first way is to simply bend it around in a circle to form a torus (or bicycle tire or doughnut, depending on how hungry you are.)

The other way is more of a challenge — bringing one end to meet the other from inside the cylinder. The problem is that in the context of Klein’s work, he wasn’t “allowed” to pierce the cylinder’s surface to get it there. Klein’s solution was simple — swing it in through the fourth dimension. Sounds like a cheat, doesn’t it?

The other way is more of a challenge — bringing one end to meet the other from inside the cylinder. The problem is that in the context of Klein’s work, he wasn’t “allowed” to pierce the cylinder’s surface to get it there. Klein’s solution was simple — swing it in through the fourth dimension. Sounds like a cheat, doesn’t it?

Actually, the cheat is in the way  that the Klein bottle is usually represented. When the glass artisan created this example, he probably brought one tube up from the bottom, sealed it to the side wall, blew a hole in the side wall at that location, and then brought the outside tube around to join there. That hole would not have satisfied Herr Klein.

that the Klein bottle is usually represented. When the glass artisan created this example, he probably brought one tube up from the bottom, sealed it to the side wall, blew a hole in the side wall at that location, and then brought the outside tube around to join there. That hole would not have satisfied Herr Klein.

If you’ve looked at my previous post in this series you probably have a pretty good idea of how he would have preferred his Fläche to be depicted — as an animation which exploits time as the fourth dimension. So here you have it.

Suppose the figure’s wall sprouts from a bud somewhere near the intersection point. After the figure has grown for a while, the earliest section of the wall begins to recede, disappearing like the Cheshire Cat but leaving its ever-expanding smile behind. By the time the growth front gets to where the bud was, there’s nothing there to intersect.

If you opt to build the “bottle” in 4-space, there’s no problem getting those two ends of the cylinder to join up. A shape that’s impossible to build in three dimensions is easy-peasy (with a little planning) in four.

If you opt to build the “bottle” in 4-space, there’s no problem getting those two ends of the cylinder to join up. A shape that’s impossible to build in three dimensions is easy-peasy (with a little planning) in four.

Yeah, yeah, the Klein bottle has lots of interesting properties, like not having an inside, but we’ll defer talking about them for a while.

Next week, getting past that pesky four-dimension limitation.

~~ Rich Olcott