<Author’s note — Side projects completed. Back to the fun stuff…>

“A cup of mud and a strawberry scone, please.”

“Sy! You’re back! Spent the winter months down in Bermuda with the onions and the eels, eh?”

“Not quite, Cal. A contract needed me on-site to monitor how well the company executed my recommendations. They did a pretty good job. They’re happy; I’m happy, paid and back home again. The weather here’s more to my liking.”

A hefty hand grabs my shoulder. “Hey, Sy, you’re back. Where ya been and how was it?”

“Sorry, Vinnie, my lips are sealed. You know how that works.”

“Yeah, I been there. Well, not there there, but. Anyways, I got a question I been saving up for you.”

“Always good to have a conversation-starter. Out with it.”

“Came from a Calvin And Hobbes comic strip some years ago but I saw it again on the internet. Calvin, that’s the kid who has a stuffed tiger named Hobbes but it talks, he’s sitting on the floor listening to something on his record player which tells you how old the strip is. His Dad comes over, points one finger at the disk’s edge and another at the label near the center. Got the picture?”

“Clear so far.”

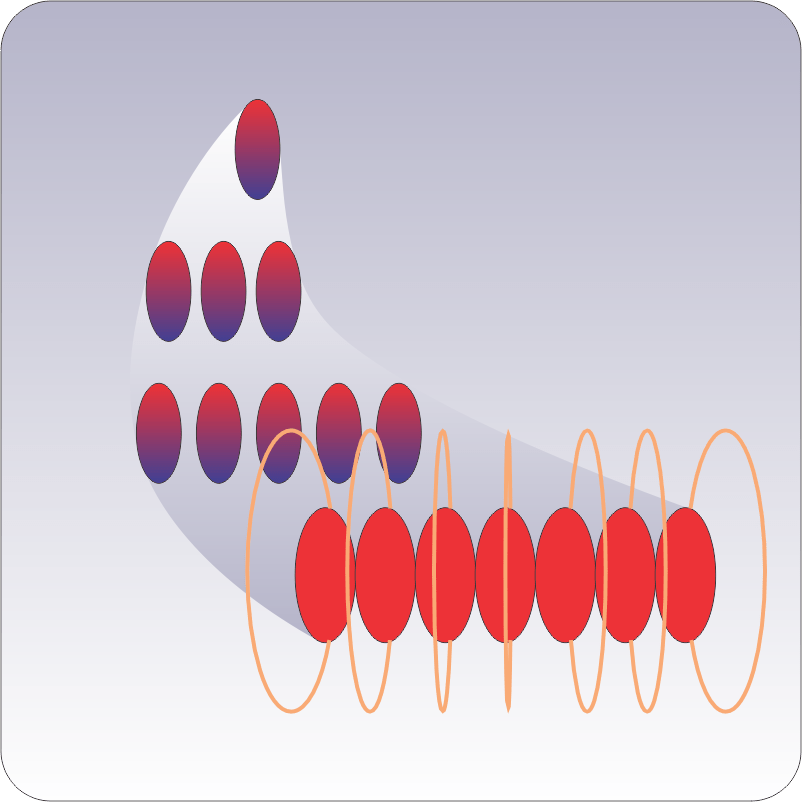

“Dad leads off, ‘Both points make a complete circle in the same amount of time, right?‘ And the kid says, yeah, and Dad’s like, ‘But this point on the edge has to make a bigger circle than this point near the center so it has to move faster. Two points on the same disk move at different speeds but they both do the same revolutions per minute‘, and the kids goes to bed all frazzled.”

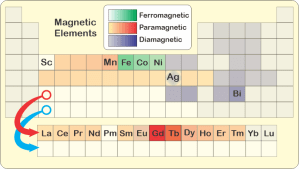

“Ah, the difference between angular speed and linear speed. The whole Earth turns once every 24 hours so Quito on the Equator does 1040 miles an hour but Helsinki up 60 degrees north goes half that.”

“Yeah, I know all about that stuff, I fly airplanes for a living, remember? That’s not my question.”

“Okay, what’s your question?”

“Suppose Calvin’s record speeds up until the label point’s going near the speed of light? What happens to the edge point?”

“Things get interesting, like Einstein-level interesting. On his way to General Relativity he did an important thought experiment about a disk like this. Sort-of like this.”

“Sort of?”

“Calvin’s disk represents a real material object, Einstein’s doesn’t. Objects made of matter have a limit to how fast you can spin them and it’s way short of lightspeed. Remember that time you were in here playing with that kid-toy top?”

“Gimme a sec… that was about centrifugal force, right, the kind that tries to shoot stuff straight out away from a spin center?”

“Sharp as ever, Vinnie. The centrifugal force per unit mass rises with the square of the rotation speed. Spin twice as fast, the force quadruples. Spin it faster and faster, eventually the outward force exceeds any material’s tensile strength. Chunks near the rim tear loose from the rest of the disk and it’s not a disk any more. Einstein imagined an infinitely strong disk that wouldn’t have that problem. In the kind of argument that good scientists love, Ehrenfest thought up a Special Relativity paradox that led Einstein to his big breakthrough.”

“A pair o’ docs, HAW!”

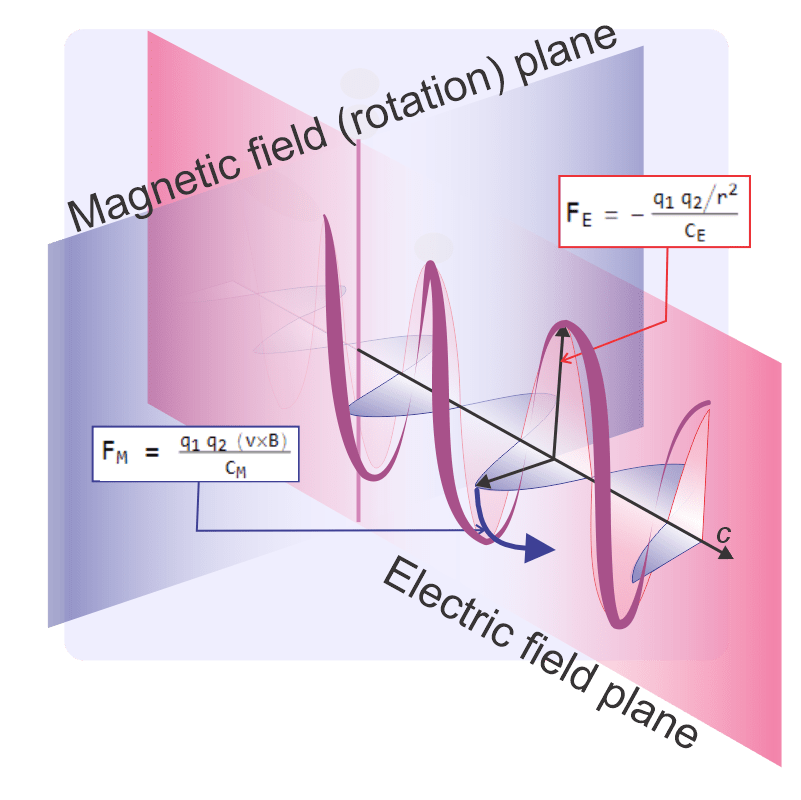

“Ha. Ha. We’ve talked about how Special Relativity says—”

“It’s gonna be frames again, ain’t it?”

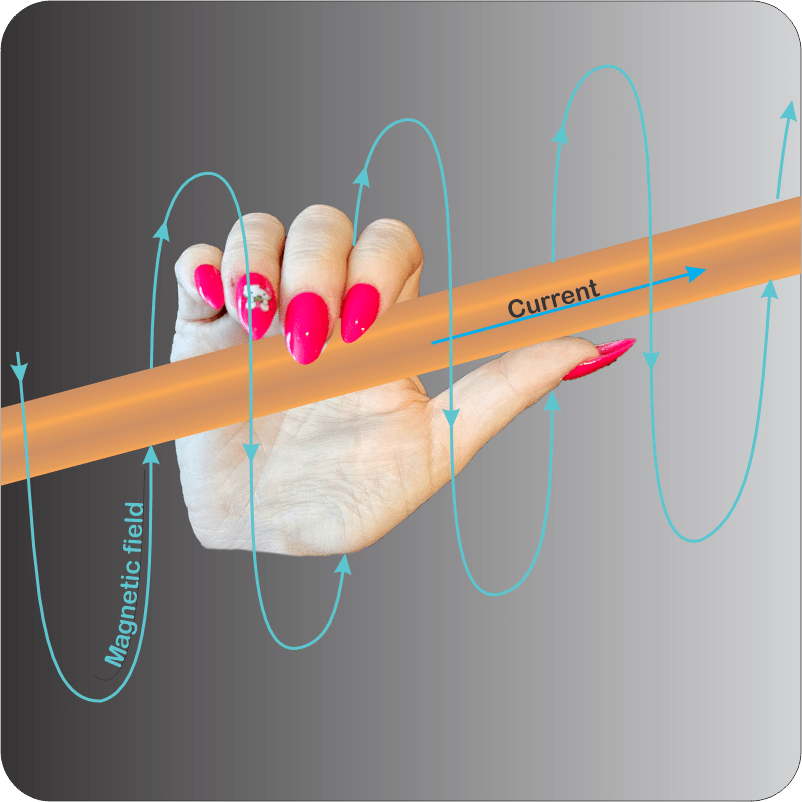

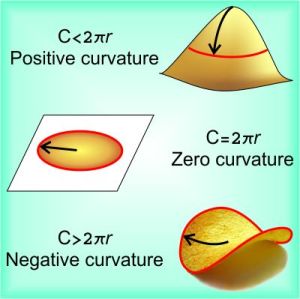

“Relativity’s always about frames, Vinnie. Ehrenfest wrote that according to Special Relativity, the radius r of a disk doesn’t change when the disk rotates, but its circumference should be compressed to something smaller than 2πr which is non‑physical. Einstein replied that Ehrenfest had it backwards. In the disk’s rotating frame, you’d measure the circumference by seeing how many yardsticks you can pack around it.”

“Short yardsticks.”

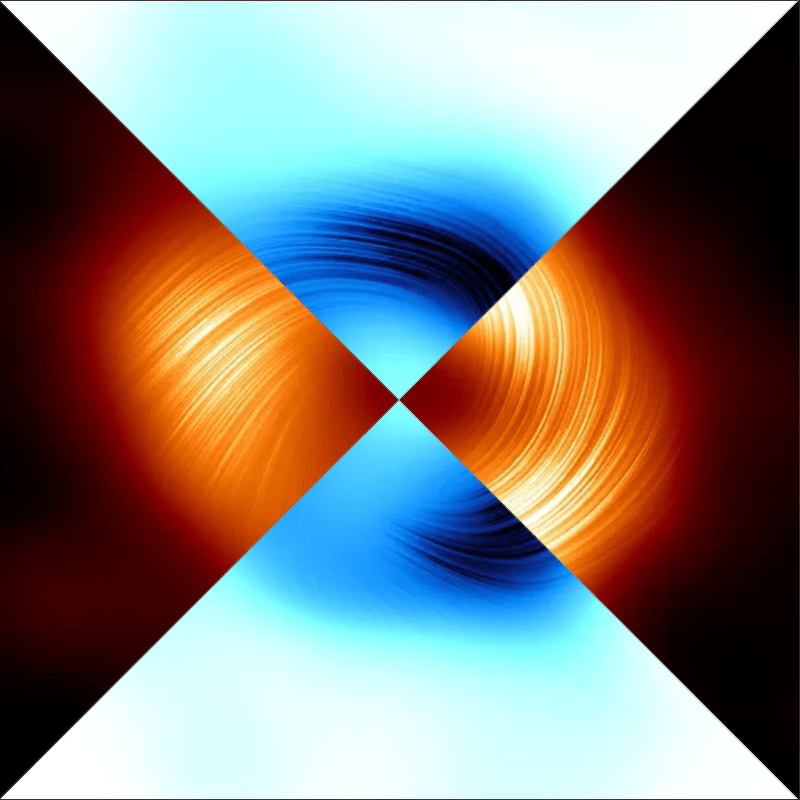

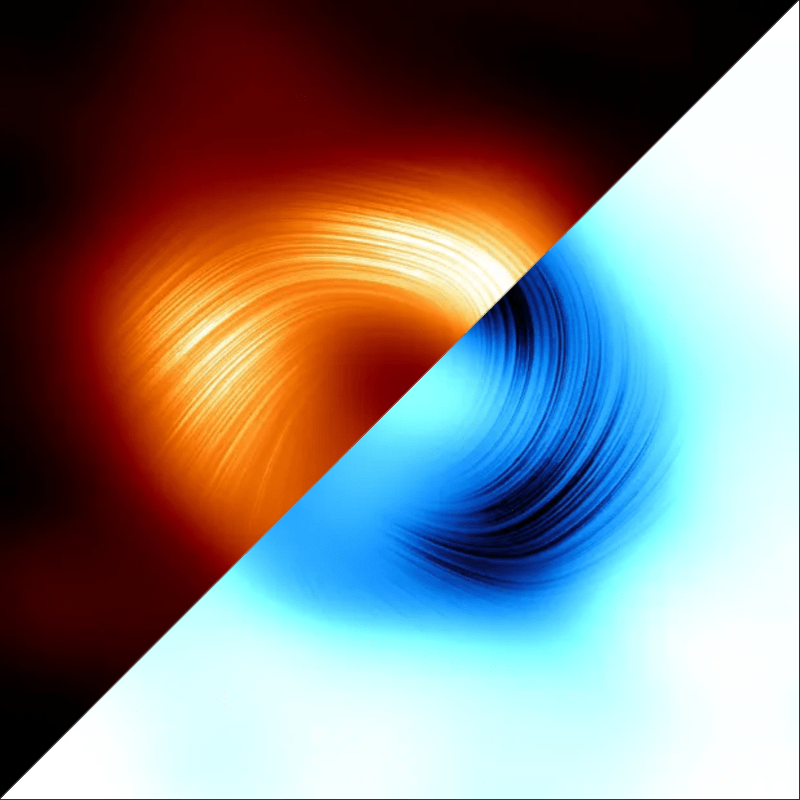

“Millimeter-sticks, whatever. Einstein pointed out that when the disk spins, each yardstick gets shorter so you can pack in more yardsticks. Rotation doesn’t shrink the circumference, it expands it by warping space from a flat plane to a curved surface like a potato chip. Chasing that idea got him to curved space and General Relativity.”

~ Rich Olcott

- Thanks to Alex, who asked the question.