“Geez, Sy. You know I hate equations. I was fine with the Phase Rule as an arithmetic thing but you’ve thrown so much algebra at me I’m flummoxed. How about something I can visualize?”

“Sorry, Vinnie, the algebra was just to show where the Rule came from. Application’s not in my bailiwick. Susan, it’s your turn.”

“Sure, Sy, this is Chemistry. Okay, Vinnie, what’s the Rule about?”

“Degrees of freedom, but I’m still not sure what that means. ‘Independent intensive variables’ doesn’t say much to me.”

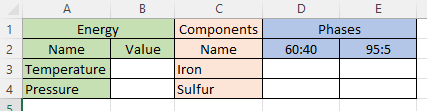

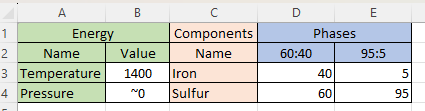

“Understandable, seeing as you don’t like equations. Visualize a spreadsheet. There’s an ‘Energy’ header over columns A and B. The second row reads ‘Name’ and ‘Value’ in those two columns. Then one row each for Temperature and Pressure.”

“This is more like it. Any numbers in the value column?”

“Not yet. They’ll be degrees of freedom, maybe. Next, ‘Components‘ in cell C1, ‘Name’ in C2 and then C rows, one for each component.”

“Do we care how much of each component?”

“Not yet.* Next visualize a multi‑column ‘Phases‘ header over one column for each phase. The second row names the phase. Below that there’s a row for each component. The whole array is for figuring how each component spreads across the phases assuming there’s enough of everything to reach equilibrium. With me?”

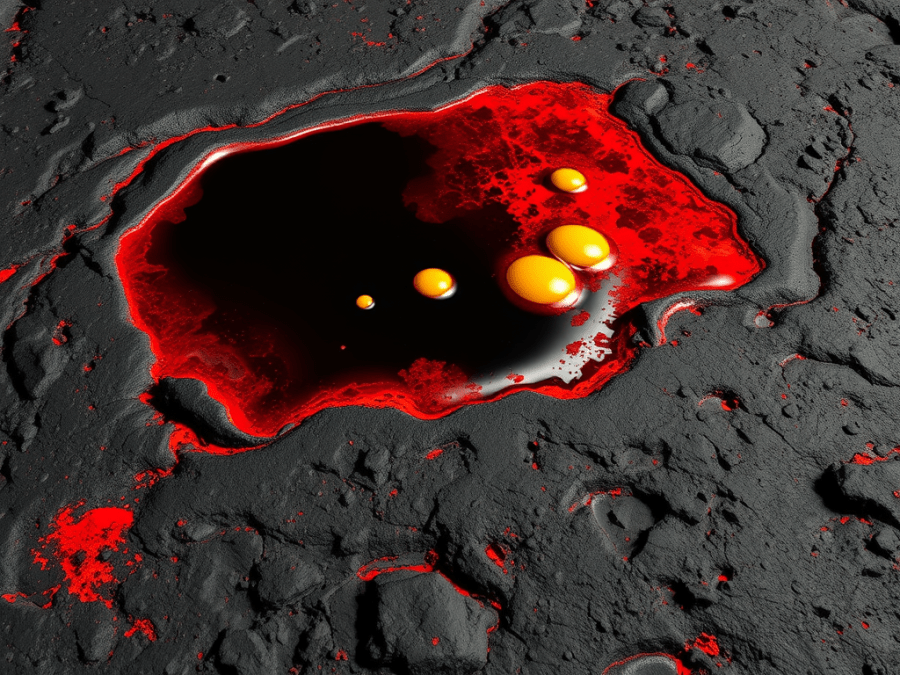

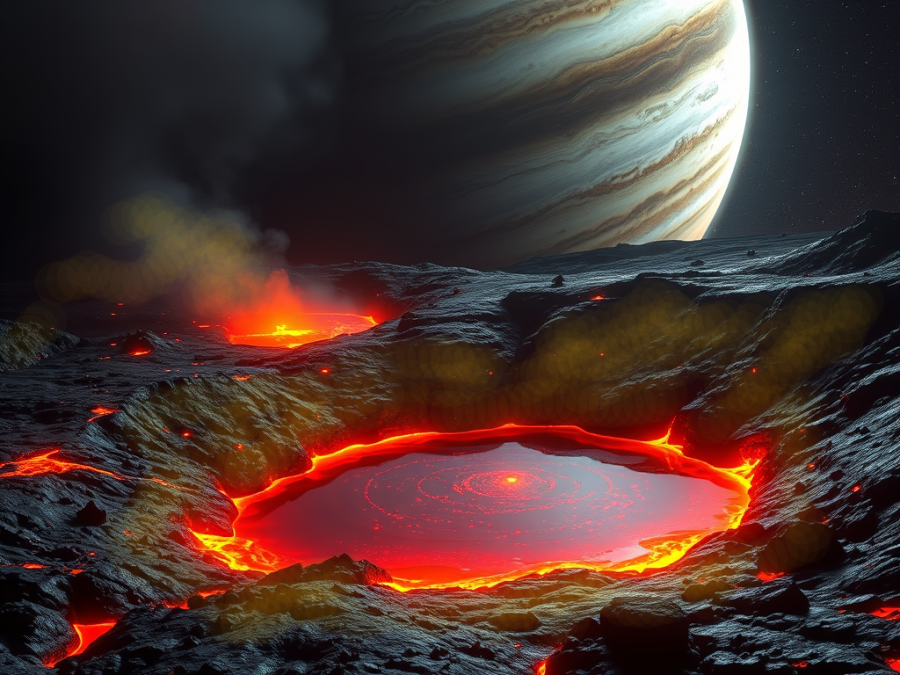

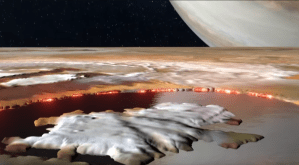

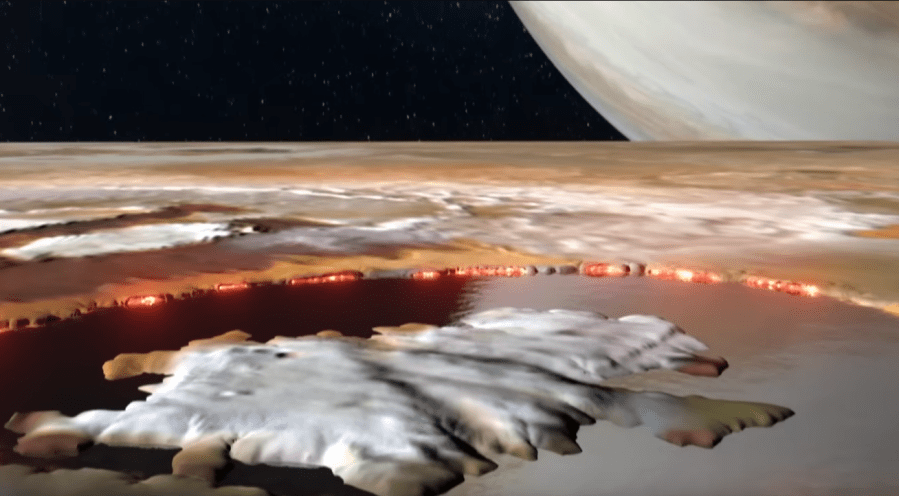

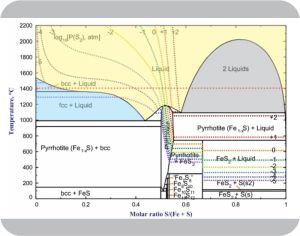

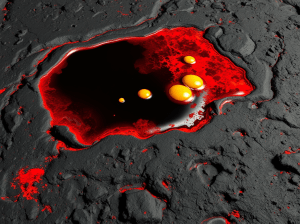

“A little ahead, I think. Take one of Kareem’s lava pools on Io, for instance. It’s got two components, iron and sulfur, and two molten phases, iron‑light 5:95 floating on top of iron‑heavy 60:40. Phase Rule says the freedom degrees is C–P+2=2–2+2, comes to 2 but that disagrees with the 6 open boxes I see.”

“But the boxes aren’t independent. Think of the interface between the two phases. One by one, atoms in each phase wander across to the other side. At equilibrium the wandering happens about as often in both directions.”

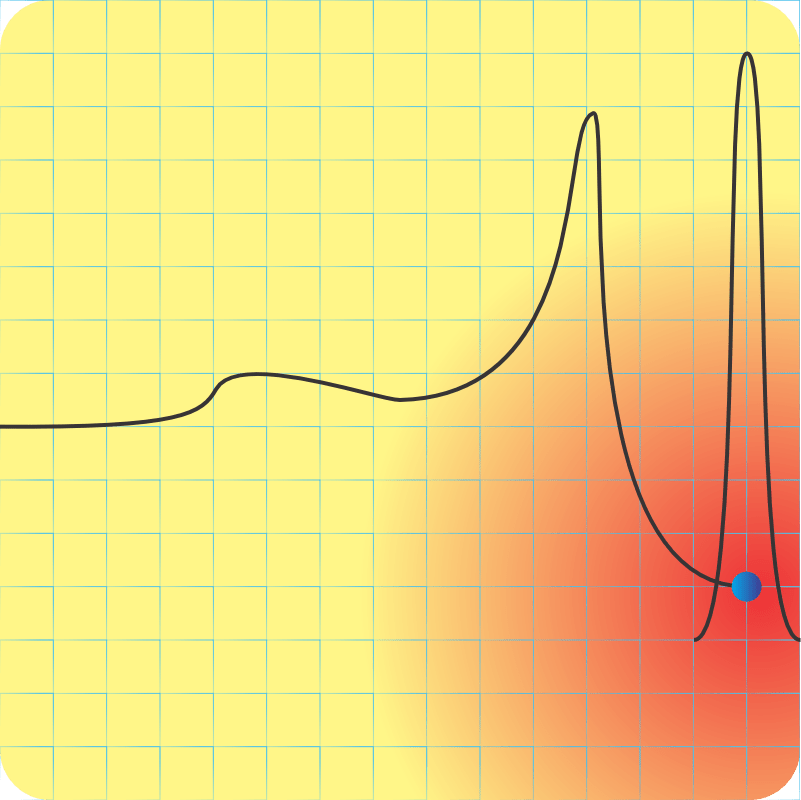

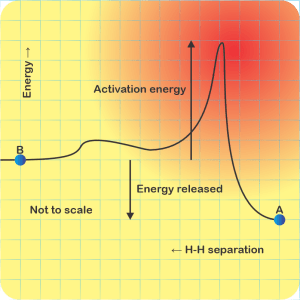

Click image to expand

“That’s your reversibility equilibrium.”

“Right, thermodynamics’ classic competition between energy and entropy — electronic energy holding things together against entropy flinging atoms everywhere. Pure iron’s a metallic electron soup that can accept a lot of sulfur without much disturbance to its energy configuration. That means sulfur’s enthalpy doesn’t differ much between the two environments and that allows easy sulfur traffic between the two phases. On the other hand, pure sulfur will accept only a little iron because iron disrupts sulfur‑sulfur moleular bonding. Steep energy barrier against iron atoms drifting into the 95:5 phase; low barrier to spitting them out. Kareem’s phase diagram for atmospheric pressure shows how things settle out for each temperature. There’s a neat equation for calculating the concentration ratios from the enthalpy differences, but you don’t like equations.”

“You’re right about that, Susan, but I smell weaseling in your temperature‑pressure dodge.”

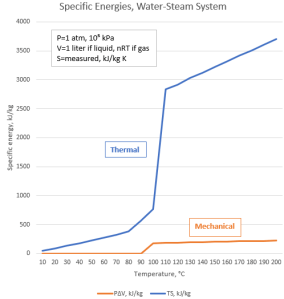

“Not really. You’ve read Sy’s posts about enthalpy’s internal energy, thermal and PV‑work components. Heat boosts entropy’s dominance and tinkers with the enthalpies.”

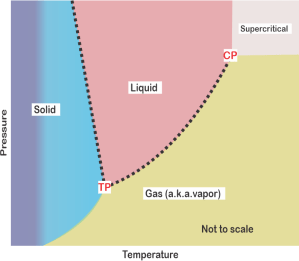

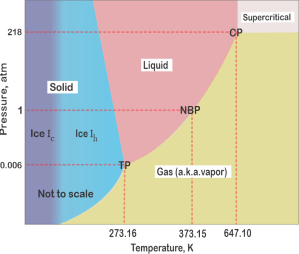

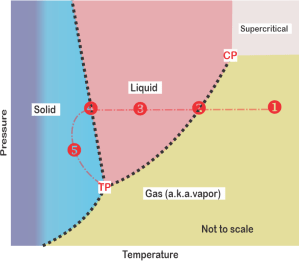

Meanwhile, I’ve been tapping Old Reliable’s screen. “I’m playing water games over here. Maybe this will help clarify the freedom. Water can be ice, liquid or vapor. At high temperature and pressure, the liquid and gas phases become a single phase we call supercritical. Here’s a sketch of water’s phase diagram. Only one component so C=1 … and a spreadsheet summarizing seven conditions.

“The first four are all at atmospheric pressure, starting at position 1 — just water vapor in a single phase so P=1, DF=2. We can change temperature and pressure independently within the phase boundaries. If we chill to point 2 liquid water condenses. If we stop there, on the boundary, we’re at equilibrium. We could change temperature and still be at equilibrium, but only if we change pressure just right so we stay on that dotted line. The temperature‑pressure linkage constraint leaves us only one degree of freedom — along the line.”

“Ah, 3 and 5 work the same way as 1 but for liquid and solid, and 4‘s like 2. The Fixed ones—?”

“One unique temperature‑pressure combination for each equilibrium. No freedoms left.”

- * Given specific quantities of iron and sulfur, chemists can calculate equilibrium quantities for each phase. Susan assigned that as a homework problem once.

~ Rich Olcott