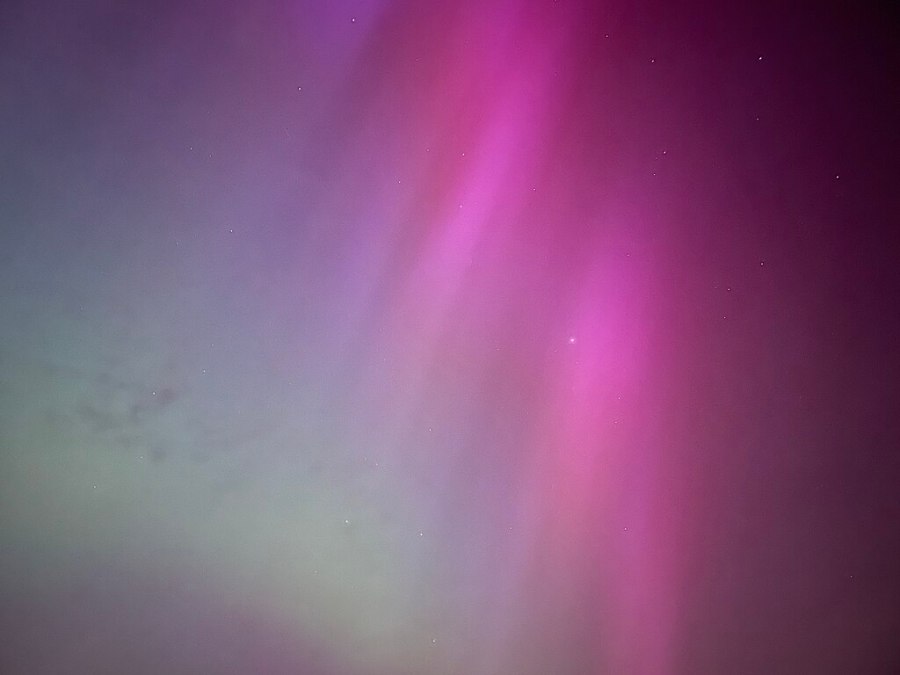

Teena’s whirling around in the night with her head thrown back. “I LUVV AURORAS!! They’re SO beautiful beautiful beautiful!”

“Yes, they are, Teena. They’re beautiful and magical, and for me it’s even better because they’re Physics at work right in front of us. Well, above us.”

“Oh, Sy, give it a rest.”

“No, really, Sis. I look at a rainbow and I’m dazzled by its glory against the rainclouds but I’m also aware that each particular glimpse of pure color comes to me by refraction through one individual droplet. Better yet, I appreciate the geometry that presents the entire spectrum in perfectly circular arcs. Marvels supported by underlying marvels. These curtains are another example of beauty emerging from hidden sources.”

“What do you mean?”

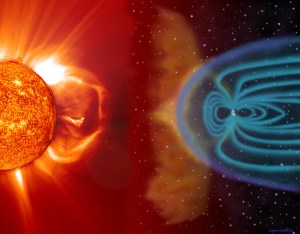

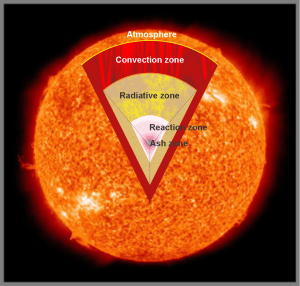

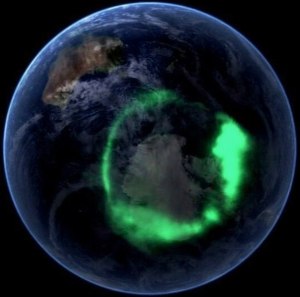

“Remember Teena’s teacher’s magnetic force lines that were organized and revealed by iron filings? Auroras are a bit like that, except one level deeper. Again we don’t see magnetic fields directly. What we do see is light coming to us from oxygen and nitrogen atoms that are bombarded by rampaging charged particles.”

“Wait, Uncle Sy, we learned that charges make magnetic fields when they move.”

“That, too. It works both ways, which is why they call it electromagnetism. A magnetic field steers protons and electrons which make their own field to push back on the first one. But my point is, the colors in each curtain and the curtains themselves tell us about the current state of the atmosphere and Earth’s magnetic field.”

“Okay, I can see how magnetic fields up there could steer charged particles to certain parts of the sky, but how does that tell us about the atmosphere? What do the colors have to do with it? Is this more rainbows and geometry?”

“Definitely not. Sis. Rainbows are sunlight refracted through water droplets. Aurora light’s emitted by atoms in our own atmosphere. Each color is like a fingerprint of a specific atom in specific circumstances. The uppermost reds, for instance come from oxygen atoms that rarely touch another atom of any kind. They’re at 150 or more kilometers altitude, way above the stratosphere. There aren’t many of them that far up which is why the curtain tops sort of fade away into infinity.”

licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

“Oooo, now it’s going green and yellow!”

“Mm-hm, the bombardment’s reaching further now. Excited oxygen atoms emit green lower down in the atmosphere where collisions happen more often and don’t give the red‑emitters a chance to do their thing. The in‑between yellow isn’t really there — it’s what your eye tells you when it sees pure red and pure green overlapping.”

“Why do the curtains have that sharp lower edge, Sy? Surely we don’t run out of oxygen there.”

“Quite the reverse. That level’s about 100 kilometers up. It’s where the atmosphere gets so thick that collisions drain away an excited atom’s energy before it gets a chance to shine.”

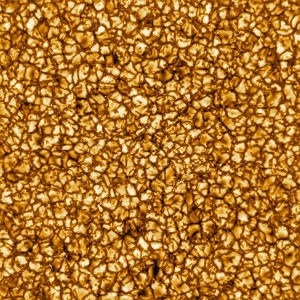

“But why are there curtains at all? Why not simply fill the sky with a smooth color wash?”

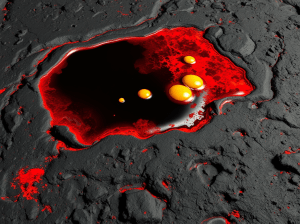

Credit: NASA, public domain

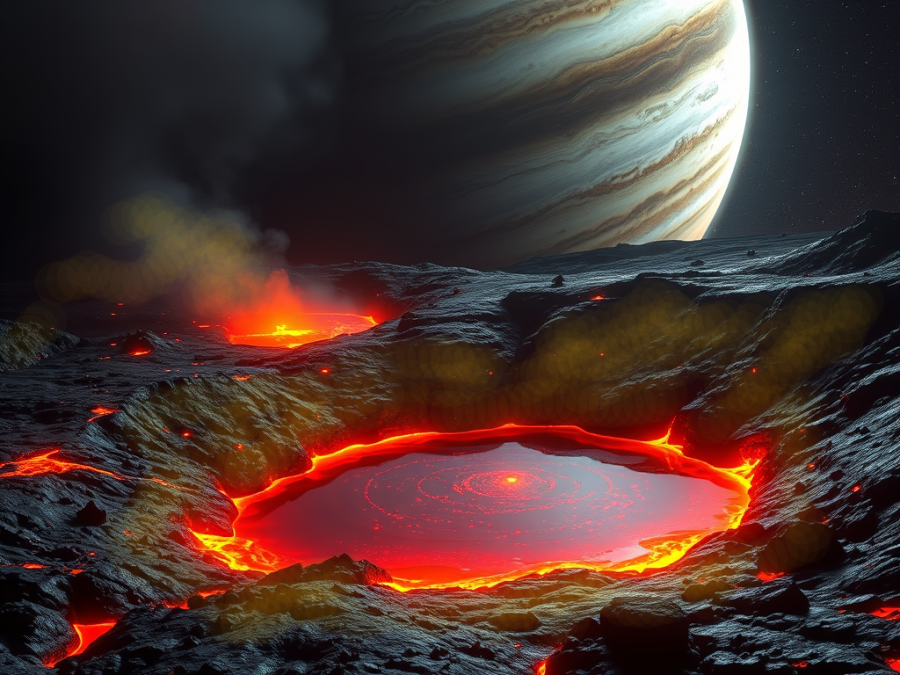

“Mars gets auroras like that, or at least Perseverance just spotted one. We don’t, thanks to our well‑ordered magnetic field. Mars’ field is lumpy and too weak to funnel incoming charged particles to special spots like our poles. Actually, those curtains are just segments of rings that go all around Earth’s magnetic axis. The rings usually lurk about 2/3 of the way to our poles but a really strong solar event like this one can push them closer to the Equator.”

“Mars gets auroras? Uncle Sy, how about other planets?”

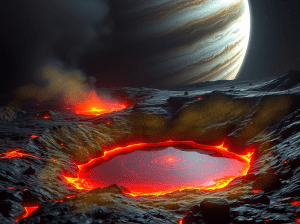

“Them, too, but theirs mostly don’t look like ours. You’d have to be able to see X‑rays on Mercury, for instance. Venus gets a general green glow for the same reason that Mars does. Jupiter is Texas for the Solar System — everything’s bigger there, including auroras in every color from X‑ray to infrared. Strong ordered field, so I’m sure there’s curtains up there.”

Sis yanks out her writer’s‑companion notebook and scribbles without looking down…

”Curtains made of colors

Colors made of air.“

licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

~ Rich Olcott