So I was telling a friend about the LIGO announcement, going on about how this new “device” will lead to a whole new kind of astronomy. He suddenly got a far-away look in his eyes and said, “I wonder how many of these the CIA has.”

The CIA has a forest of antennas, but none of them can do what LIGO does. That’s because of the physics of how it works, and what it can and cannot detect. (If you’re new to this topic, please read last week’s post so you’ll be up to speed on what follows. Oh, and then come back here.)

There are remarkable parallels between electromagnetism and gravity. The ancients knew about electrostatics — amber rubbed by a piece of cat fur will attract shreds of dry grass. They certainly knew about gravity, too. But it wasn’t until 100 years after Newton wrote his Principia that Priestly and then Coulomb found that the electrostatic force law, F = ke·q1·q2 / r2, has the same form as Newton’s Law of Gravity, F = G·m1·m2 / r2. (F is the force between two bodies whose centers are distance r apart, the q‘s are their charges and the m‘s are their masses.)

Almost a century later, James Clerk Maxwell (the bearded fellow at left) wrote down his electromagnetism equations that explain how light works. Half a century later, Einstein did the same for gravity.

Almost a century later, James Clerk Maxwell (the bearded fellow at left) wrote down his electromagnetism equations that explain how light works. Half a century later, Einstein did the same for gravity.

But interesting as the parallels may be, there are some fundamental differences between the two forces — fundamental enough that not even Einstein was able to tie the two together.

One difference is in their magnitudes. Consider, for instance, two protons. Running the numbers, I found that the gravitational force pulling them together is a factor of 1036 smaller than the electrostatic force pushing them apart. If a physicist wanted to add up all the forces affecting a particular proton, he’d have to get everything else (nuclear strong force, nuclear weak force, electromagnetic, etc.) nailed down to better than one part in 1036 before he could even detect gravity.

But it’s worse — electromagnetism and gravity don’t even have the same shape.

(graphic from WikiMedia Commons, posted by Lookang and Fu-Kwun Hwang)

A word first about words. Electrostatics is about pure straight-line-between-centers (longitudinal) attraction and repulsion — that’s Coulomb’s Law. Electrodynamics is about the cross-wise (transverse) forces exerted by one moving charged particle on the motion of another one. Those forces are summarized by combining Maxwell’s Equations with the Lorenz Force Law. A moving charge gives rise to two distinct forces, electric and magnetic, that operate at right angles to each other. The combined effect is called electromagnetism.

The effect of the electric force is to vibrate a charge along one direction transverse to the wave. The magnetic force only affects moving charges; it acts to twist their transverse motion to be perpendicular to the wave. An EM antenna system works by sensing charge flow as electrons move back and forth under the influence of the electric field.

Gravitostatics uses Newton’s Law to calculate longitudinal gravitational interaction between masses. That works despite gravity’s relative weakness because all the astronomical bodies we know of appear to be electrically neutral — no electrostatic forces get in the way. A gravimeter senses the strength of the local gravitostatic field.

Gravitodynamics is completely unlike electrodynamics. Gravity’s transverse “force” doesn’t act to move a whole mass up and down like Maxwell’s picture at left. Instead, as shown by Einstein’s picture, gravitational waves stretch and compress while leaving the center of mass in place. I put “force” in quotes because what’s being stretched and compressed is space itself. See this video for a helpful visualization of a gravitational wave.

Gravitodynamics is completely unlike electrodynamics. Gravity’s transverse “force” doesn’t act to move a whole mass up and down like Maxwell’s picture at left. Instead, as shown by Einstein’s picture, gravitational waves stretch and compress while leaving the center of mass in place. I put “force” in quotes because what’s being stretched and compressed is space itself. See this video for a helpful visualization of a gravitational wave.

LIGO is neither a telescope nor an electromagnetic antenna. It operates by detecting sudden drastic changes in the disposition of matter within a “small” region. In LIGO’s Sept 14 observation, 1031 kilograms of black hole suddenly ceased to exist, converted to gravitational waves that spread throughout the Universe. By comparison, the Hiroshima explosion released the energy of 10-6 kilograms.

Seismometers do a fine job of detecting nuclear explosions. Hey, CIA, they’re a lot cheaper than LIGO.

~~ Rich Olcott

The experiment consists of shooting laser beams out along both arms, then comparing the returned beams.

The experiment consists of shooting laser beams out along both arms, then comparing the returned beams.

It all started with Newton’s mechanics, his study of how objects affect the motion of other objects. His vocabulary list included words like force, momentum, velocity, acceleration, mass, …, all concepts that seem familiar to us but which Newton either originated or fundamentally re-defined. As time went on, other thinkers added more terms like power, energy and action.

It all started with Newton’s mechanics, his study of how objects affect the motion of other objects. His vocabulary list included words like force, momentum, velocity, acceleration, mass, …, all concepts that seem familiar to us but which Newton either originated or fundamentally re-defined. As time went on, other thinkers added more terms like power, energy and action. There is another way to get the same dimension expression but things aren’t not as nice there as they look at first glance. Action is given by the amount of energy expended in a given time interval, times the length of that interval. If you take the product of energy and time the dimensions work out as (ML2/T2)*T = ML2/T, just like Heisenberg’s Area.

There is another way to get the same dimension expression but things aren’t not as nice there as they look at first glance. Action is given by the amount of energy expended in a given time interval, times the length of that interval. If you take the product of energy and time the dimensions work out as (ML2/T2)*T = ML2/T, just like Heisenberg’s Area.

For practice using Heisenberg’s Area, what can we say about the atom? (If you’re checking my math it’ll help to know that the Area, h/4π, can also be expressed as 0.5×10-34 kg m2/s; the mass of one hydrogen atom is 1.7×10-27 kg; and the speed of light is 3×108 m/s.) On average the atom’s position is at the cube’s center. Its position range is one meter wide. Whatever the atom’s average momentum might be, our measurements would be somewhere within a momentum range of (h/4π kg m2/s) / (1 m) = 0.5×10-34 kg m/s. A moving particle’s momentum is its mass times its velocity, so the velocity range is (0.5×10-34 kg m/s) / (1.7×10-27 kg) = 0.3×10-7 m/s.

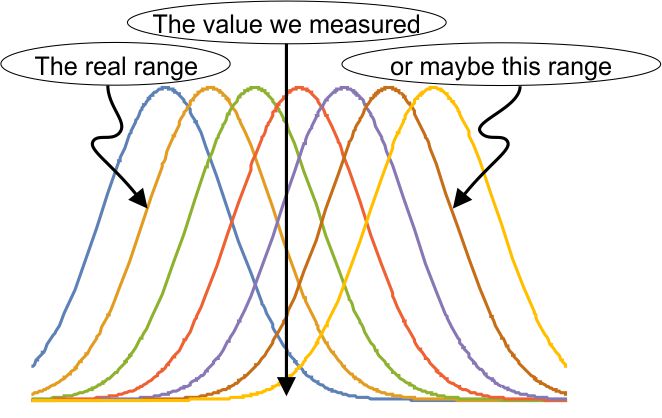

For practice using Heisenberg’s Area, what can we say about the atom? (If you’re checking my math it’ll help to know that the Area, h/4π, can also be expressed as 0.5×10-34 kg m2/s; the mass of one hydrogen atom is 1.7×10-27 kg; and the speed of light is 3×108 m/s.) On average the atom’s position is at the cube’s center. Its position range is one meter wide. Whatever the atom’s average momentum might be, our measurements would be somewhere within a momentum range of (h/4π kg m2/s) / (1 m) = 0.5×10-34 kg m/s. A moving particle’s momentum is its mass times its velocity, so the velocity range is (0.5×10-34 kg m/s) / (1.7×10-27 kg) = 0.3×10-7 m/s. elaborate mathematical structure. If the measurement is a quantum mechanical result, part of that structure is our familiar bell-shaped curve. It’s an explicit recognition that way down in the world of the very small, we can’t know what’s really going on. Most calculations have to be statistical, predicting an average and an expected range about that average. That prediction may or may not pan out, depending on what the experimentalists find.

elaborate mathematical structure. If the measurement is a quantum mechanical result, part of that structure is our familiar bell-shaped curve. It’s an explicit recognition that way down in the world of the very small, we can’t know what’s really going on. Most calculations have to be statistical, predicting an average and an expected range about that average. That prediction may or may not pan out, depending on what the experimentalists find. So there could be a collection of bell-curves gathered about the experimental result. Remember those

So there could be a collection of bell-curves gathered about the experimental result. Remember those