“Here’s the poly bag wiff our meals, Johnny. ‘S got two boxes innit, but no labels which is which.”

“I ordered the mutton pasty, Jennie, anna fish’n’chips for you.”

“You c’n have this box, Johnny. I’ll take the other one t’ my place to watch telly.”

…

<ring>

” ‘Ullo, Jennie? This is Johnny. The box over ‘ere ‘as the fish. You’ve got mine!”

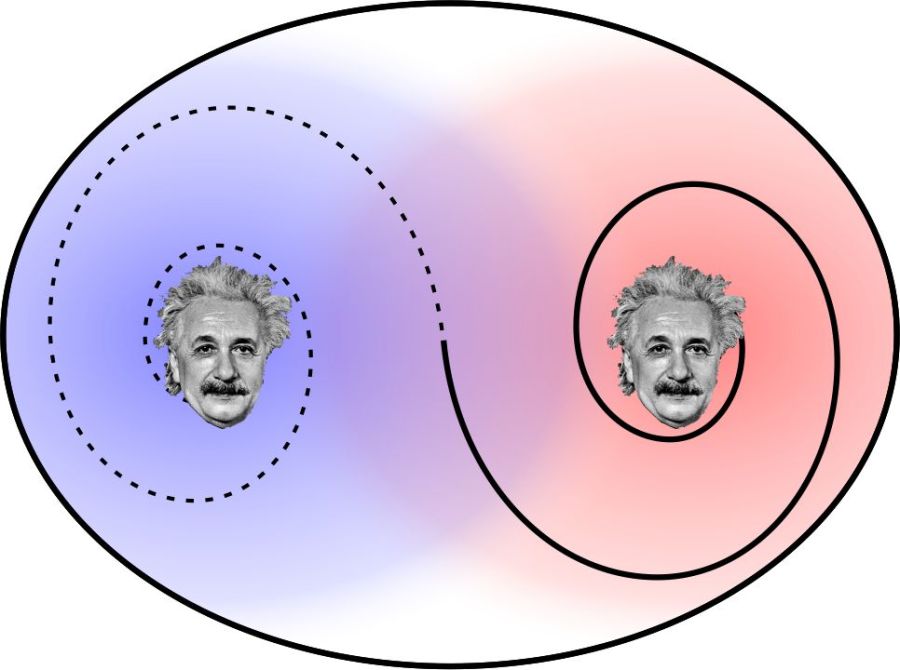

In a sense their supper order arrived in an entangled state. Our friends knew what was in both boxes together, but they didn’t know what was in either box separately. Kind of a Schrödinger’s Cat situation — they had to treat each box as 50% baked pasty and 50% fried codfish.

But as soon as Johnny opened one box, he knew what was in the other one even though it was somewhere else. Jennie could have been in the next room or the next town or the next planet — Johnnie would have known, instantly, which box had his meal no matter how far away that other box was.

By the way, Jennie was free to open her box on the way home but that’d make no difference to Johnnie — the box at his place would have stayed a mystery to him until either he opened it or he talked to her.

Information transfer at infinite speed? Of course not, because neither hungry person knows what’s in either box until they open one or until they exchange information. Even Skype operates at light-speed (or slower).

Information transfer at infinite speed? Of course not, because neither hungry person knows what’s in either box until they open one or until they exchange information. Even Skype operates at light-speed (or slower).

But that’s not quite quantum entanglement, because there’s definite content (meat pie or batter-fried cod) in each box. In the quantum world, neither box holds something definite until at least one box is opened. At that point, ambiguity flees from both boxes in an act of global correlation.

There’s strong experimental evidence that entangled particles literally don’t know which way is up until one of them is observed. The paired particle instantaneously gets that message no matter how far away it is.

Niels Bohr’s Principle of Complementarity is involved here. He held that because it’s impossible to measure both wave and particle properties at the same time, a quantized entity acts as a wave globally and only becomes local when it stops somewhere.

Here’s how extreme the wave/particle global/local thing can get. Consider some nebula a million light-years away. A million years ago an electron wobbled in the nebular cloud, generating a spherical electromagnetic wave that expanded at light-speed throughout the Universe.

courtesy of NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope

Last night you got a glimpse of the nebula when that lightwave encountered a retinal cell in your eye. Instantly, all of the wave’s energy, acting as a photon, energized a single electron in your retina. That particular lightwave ceased to be active elsewhere in your eye or anywhere else on that million-light-year spherical shell.

Surely there was at least one other being, on Earth or somewhere else, that was looking towards the nebula when that wave passed by. They wouldn’t have seen your photon nor could you have seen any of theirs. Somehow your wave’s entire spherical shell, all 1012 square lightyears of it, instantaneously “knew” that your eye’s electron had extracted the wave’s energy.

But that directly contradicts a bedrock of Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity. His fundamental assumption was that nothing (energy, matter or information) can go faster than the speed of light in vacuum. STR says it’s impossible for two distant points on that spherical wave to communicate in the way that quantum theory demands they must.

Want some irony? Back in 1906, Einstein himself “invented” the photon in one of his four “Annus mirabilis” papers. (The word “photon” didn’t come into use for another decade, but Einstein demonstrated the need for it.) Building on Planck’s work, Einstein showed that light must be emitted and absorbed as quantized packets of energy.

It must have taken a lot of courage to write that paper, because Maxwell’s wave theory of light had been firmly established for forty years prior and there’s a lot of evidence for it. Bottom line, though, is that Einstein is responsible for both sides of the wave/particle global/local puzzle that has bedeviled Physics for a century.

~~ Rich Olcott