No-one else in the place so Jeremy’s been eavesdropping on my conversation with Cal. “Lieutenant Leaphorn says there are no coincidences.”

“Oh, you’ve read Tony Hillerman’s mystery stories then?”

“Of course, Mr Moire. It’s fun getting a sympathetic outsider’s view of what my family and Elders have taught me. He writes Leaphorn as a very wise man.”

“With some interesting quirks for a professional crime solver. He doesn’t trust clues, yet he does trust apparent coincidences enough to follow up on them.”

“It does the job for him, though.”

“Mm‑hm, but that’s in stories. Have you read any of Terry Pratchett’s Discworld books?”

“What are they about?”

Carpe Jugulum

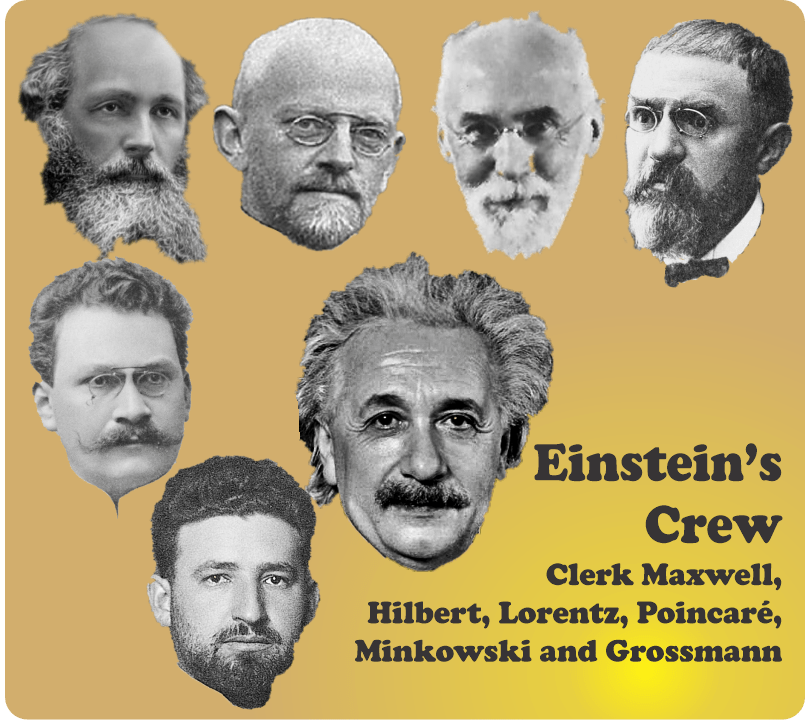

“Pretty much everything, but through a lens of laughter and anger. Rather like Jonathan Swift. Pratchett was one of England’s most popular authors, wrote more than 40 novels in his too‑brief life. He identified narrativium as the most powerful force in the human universe. Just as the nuclear strong force holds the atomic nucleus together using gluons and mesons, narrativium holds stories together using coincidences and tropes.”

“Doesn’t sound powerful.”

“Good stories, ones that we’d say have legs, absolutely must have internal logic that gets us from one element to the next. Without that narrative flow they just fall apart; no‑one cares enough to remember them. As a writer myself, I’ve often wrestled with a story structure that refused to click together — sparse narrativium — or went in the wrong direction — wayward narrativium.”

“You said ‘the human universe’ like that’s different from the Universe around us.”

“The story universe is a multiverse made of words, pictures and numbers, crafted by humans to explain why one event follows another. The events could be in the objective world made of atoms or within the story world itself. Legal systems, history, science, they’re all pure narrativium. So is money, mostly. We don’t know of anything else in the Universe that builds stories like we do.”

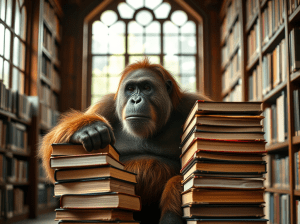

“How about apes?”

“An open question, especially for orangutans. One of Pratchett’s important characters is The Librarian, a university staff member who had accidentally been changed from human to orangutan. He refuses to be restored because he prefers his new form. Which gives you a taste of Pratchett’s humor and his high regard for orangutans. But let’s get back to Leaphorn and coincidences.”

“Regaining control over your narrativium, huh?”

“Guilty as charged. Leaphorn’s standpoint is that there are no coincidences because the world runs on patterns, that events necessarily connect one to the next. When he finds the pattern, he solves the mystery.”

“Very Diné. Our Way is to look for and restore harmony and balance.”

“Mm‑hm. But remember, Leaphorn is only a character in Hillerman’s narrativium‑driven stories. The atom‑world may not fit that model. A coincidence for you may not be a coincidence for someone else, depending. Those two concurrent June novas, for example. For most of the Universe they’re not concurrent.”

“I hope this doesn’t involve relativistic clocks. Professor Hanneken hasn’t gotten us to Einstein’s theories yet.”

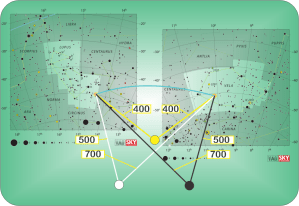

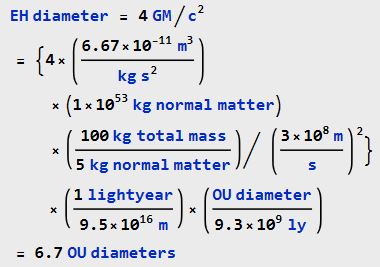

“No relativity; this is straight geometry. Rømer could have handled it 350 years ago.” <brief tapping on Old Reliable’s screen> “Here’s a quick sketch and the numbers are random. The two novas are connected by the blue arc as we’d see them in the sky if we were in Earth’s southern hemisphere. We live in the yellow solar system, 400 lightyears from each of them so we see both events simultaneously, 400 years after they happened. We call that a coincidence and Cal’s skywatcher buddies go nuts. Suppose there are astronomers on the white and black systems.”

<grins> “Those four colors aren’t random, Mr Moire.”

<grins back> “Caught me, Jeremy. Anyway, the white system’s astronomers see Vela’s nova 200 years after they see the one in Lupus. The astronomers in the black system record just the reverse sequence. Neither community even thinks of the two as a pair. No coincidence for them, no role for narrativium.”

~ Rich Olcott

- This is the 531st post in an unbroken decade‑long weekly series that I originally thought might keep going for 6 months. <whew!>