“Ya think there’s water on the Psyche asteroid, Kareem?”

“No more than a smidgeon, Cal.”

“Why so little? They’ve found hundreds of tons of it on the Moon.”

“Wait, water found on the moon? I’d heard about the Chinese rover finding sulfur but I didn’t think anybody’s gotten into a shadowy area that may be icy because sunlight never heats it.”

“Catch up, Eddie. We’ve known about hydrogen on the Moon since the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter almost 15 years ago. We just weren’t sure any of it was water‑ice. Could be hydroxyls coating the outside of oxide and silicate moon rocks, or water of crystallization locked into mineral structures.”

“That’s the kind of caveat I’d expect from a chemist, Susan, throwing chemical complexity into the mess.”

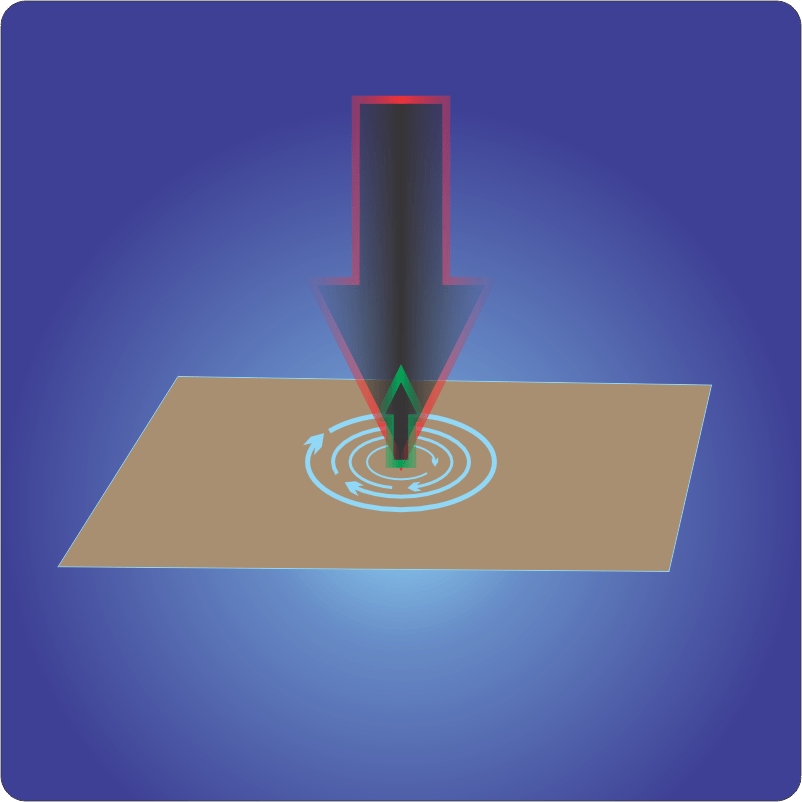

“Well, sure, Sy. Silicate chemistry is a mess. Nature rarely gives us neat lab‑purified materials. The silicon‑oxygen lattice in a silicate can host almost any combination of interstitial metal ions. On top of that, the solar wind showers the Moon with atomic and ionic hydrogens eager to bond with surface oxygens and maybe even migrate further into the bulk. The Apollo astronauts found plagioclase rocks, right? That name covers a whole range of aluminum‑silicate compositions from calcium‑rich like we find in meteorites to sodium‑rich that are common in Earth rocks. The astronauts’ rocks were dry, dry, dry, but that collecting was done where the missions landed, near the Moon’s equator. What’s got the geologists all excited is satellite data from around the Moon’s south pole. The spectra suggest actual water molecules at or just below the surface there. Lots of water.”

“Mm-hm, me and a lot of other Earth‑historians would love to compare that water’s isotopic break‑out against Earth and the asteroids and comets.”

“Understood, Kareem. but why so down on Psyche having water?”

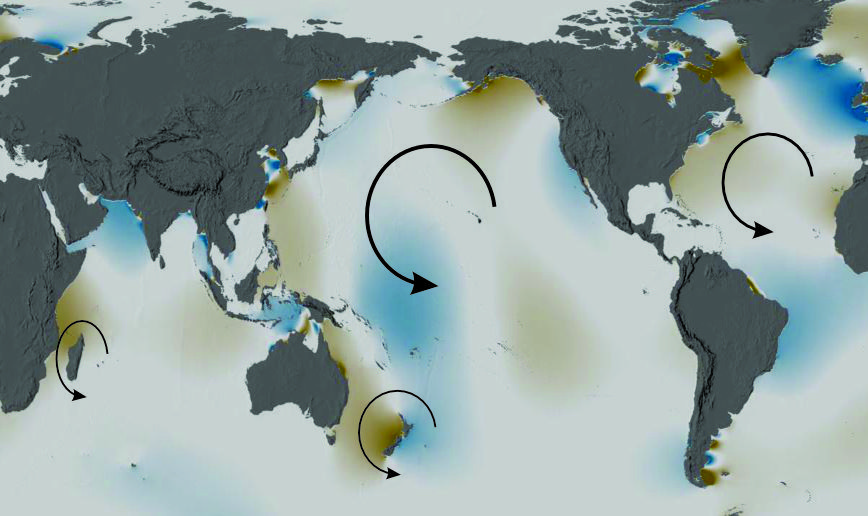

“Two arguments. Attenuation, for one. Psyche is 2½ times farther from the Sun than the Earth‑Moon system. Per unit area at the target, stuff coming out of the Sun thins out as the square of the distance. The solar wind near Psyche is at least 85% weaker than what the Moon gets. If Psyche’s built up any watery skin it’s much thinner than the Moon’s. And that’s assuming that they’re both covered with the same kind of rocks.”

“The other argument?”

“Depends on Psyche’s density which we’re still zeroing in on.”

“This magazine article says it’s denser than iron. That’s why they’re shouting ‘GOLD! GOLD! GOLD!‘ like Discworld Dwarfs, ’cause gold is heavier than iron.”

“Shouldn’t that be ‘dwarves‘?”

“Not according to Terry Pratchett. He ought to know ’cause he wrote the books about them.”

“True. So’s saying gold and a lot of the other precious metals are much denser than iron. Unfortunately, it now looks like Psyche isn’t. An object’s density is its mass divided by its volume. You measure an asteroid’s mass by how it affects the orbits of nearby asteroids. That’s hard to do when asteroids average as far apart as the Moon and the Earth. Early mass estimates were as much as three times too big. Also, Psyche’s potato‑shaped. Early size studies just happened to have worked from images taken when the asteroid was end‑on to us. Those estimates had the volume too small. Divide too‑big by too‑small you get too‑big squared.”

“So we still don’t know the density.”

“As I said, we’re zeroing in. Overall Psyche seems to be a bit denser than your average stony meteorite but nowhere near as dense as iron, let alone gold or platinum. We’re only going to get a good density value when our spacecraft of known mass orbits Psyche at close range.”

“No gold?”

“I wouldn’t say none. Probably about the same gold/iron ratio that we have here on Earth where you have to process tonnes of ore to recover grams of gold. Your best hope as an astro‑prospector is that Psyche’s made of solid metal, but in the form of a rubble‑pile like we found Ryugu and Bennu to be. That would bring the average density down to the observed range. It’d also let you mine the asteroid chunk‑wise. Oh, one other problem…”

“What’s that?”

“Transportation costs.”

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU

~~ Rich Olcott