“That point’s kinda weak, Sy. The NANOGrav team says 15 years of pulsar timing data let them hear the Universe humming. What’s the difference if they call it a hum or a rumble or a warble?”

“Not much, Vinnie. Matter of taste and scale, I guess. As a human I think of a ‘hum‘ as something in the auditory range, roughly 60‑120 cycles per second. Whatever these folks have found, it rumbles in years per cycle. Scaled to the Sun’s ten‑billion‑year lifetime I suppose that’d be a supersonic screech.”

“Whatever they’ve found? We don’t know?”

“Not yet, Al. The team likes one hypothesis but it’ll take years to collect enough data for firm support or refutation.”

“In addition to the 15 years‑worth they’ve got already? Why not just add more antennas?”

“What they’re following changes so slowly they need a long baseline to have confidence that jiggles they see are real. Part of this paper is about conclusions the team reached after they stuck a few extra years of old data onto the front of their time series.”

“You can do that?”

“Sure. The series is just a big database, like a spreadsheet with a page for each pulsar and a row on that page for each blink. The row captures the recorded time for the blink’s peak, but also a bunch of other data like measures related to pulse width and asymmetry, the corrected peak time, identifiers for the reporting observatory and reference time standard—”

“Corrected time? Looks suspicious. What did they correct for?”

“Of course you’re suspicious, Vinnie, but so are they and so are other astronomers. You don’t want to make a big announcement like this unless you’ve checked everything for error sources. For instance, Earth moving around the Sun means we’re a little closer to a particular pulsar at one time of year, further away six months later.”

“So you correct the timings to what they’d be at the Sun’s center, right?”

“That’s just for starters. Jupiter and the Sun orbit around their common center of gravity on an 11.8‑year cycle. The researchers had to pull data from the Juno mission to correct for the Sun’s personal waltz. Of course the Solar System is moving relative to the stellar background, another correction. Then maybe the pulsar itself is part of a binary, happens a lot, and it’s probably moving through the sky, too — lots of careful corrections. That’s step one.”

“Then what?”

“Use each pulsar’s corrected timings to build a mathematical model of its idealized behavior. Once you know what’s ‘normal‘, you can start talking about jiggles that deviate from normal.”

“Reminds me of the ephemeris trick — sort of build an artificial pulsar to compare against.”

“Exactly the same idea, Vinnie, and by the way, ephemerides are still used but not to define the length of a second. Step three is statistical analysis: compare all possible deviation histories, every pulsar against every other pulsar.”

“Sounds like a lot of work, even for a computer. So what did they find?”

“Well, what they observed was that the pulsar timings we received weren’t as absolutely regular as they would have been with a static gravitational field. The overall picture resembled fog in a noisy room, waves of every size skittering in every direction and messing up reception. When the researchers broke that picture down by frequency, the waves shorter than 21 months or so added up to just white noise, complete randomness.”

“A hiss, not a hum. What about the longer waves?”

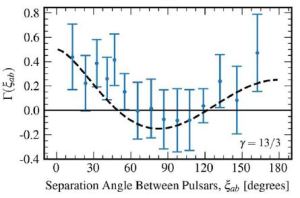

“Red noise — jiggles heavy‑loaded on longer wavelengths out to the 16‑year maximum their data’s good for so far. But that’s not all. When they plotted jiggle correlation between pulsars separated at different angles across the sky, the curve mostly matched a prediction for the gravitational wave pattern that would be generated by a large number of randomly distributed independent sources.”

“Lots of sources, which would be…?”

“We don’t know. One hypothesis is that they’re pairs of supermassive black holes orbiting each other at the centers of merged galaxies. But I’ve read another paper giving a dozen other explanations. Everyone’s waiting for more data.”

~~ Rich Olcott