“Uncle Sy, why is PV=nRT the Ideal Gas Equation? Is it because it’s so simple but makes sense anyway?”

“It is ideal that way, Teena, but it’s simply an equation about gases that are ideal. Except there aren’t any. Real gases come close but don’t always follow the rule.”

“Why not? Are they sneaky?”

“Your kind of question. We like to think of gas particles as tiny ping‑pong balls that just bounce off of each other like … ping‑pong balls. That’s mostly true most of the time for most kinds of gas. One exception has to do with stickiness. Water’s one of the worst cases because its H2O molecules like to chain up. When two H2Os collide, if they’re pointed in the right directions they share a hydrogen atom like a bridge and stick together. If that sort of stickiness happens a lot then the quantity measure n acts like it’s less than we’d expect. That makes the PV product smaller.”

“I bet that doesn’t happen much when the gas is really hot. Two particles might stick and then BANG! another particle hits ’em and breaks it up!”

“Good thinking and that’s true. But there’s another kind of exception that holds even at high temperatures. A well‑behaved gas is mostly empty space because the ping‑pong balls are far apart unless they’re actually colliding. But suppose you squeeze out nearly all of the empty space and then try to squeeze some more.”

“Oh! The pressure gets even bigger than the equation says it should because you can’t squeeze the particles any smaller than they are, right?”

“Exactly.”

“Well, if the equation has these problems, why do we even use it at all?”

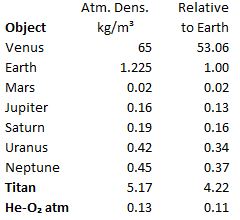

“Because it’s good enough, enough of the time, and we know when not to use it. I’ll give you an example. One of my clients wanted to know air density at ground level on Saturn’s moon Titan and all the planets that have an atmosphere.” <showing Old Reliable’s screen> “I found the planet data I needed in NASA’s Planetary Science website, but I had to do my own calculation for Titan. The pressure’s not crazy high and the temperature’s chilly but not quite cold enough to liquify nitrogen so the situation’s in‑range for the Ideal Gas Equation.”

“What’s a Pa?”

“That’s the symbol for a pascal, the unit of pressure. kPa is kilopascals, just like kg is kilograms. Earth’s atmospheric pressure is about 100 kPa.”

“Reliable says Wikipedia says Titan’s air is mostly nitrogen like Earth’s air is. Titan’s just a moon so it has to be smaller than Earth so its gravity must be smaller, too. Why is its atmosphere so much denser?”

“The cold. Titan’s air is 200 kelvins colder than Earth’s average temperature. You’re right, an individual gas particle feels a smaller pull of gravity on Titan, but it doesn’t have much kinetic energy to push its neighbors away so they all crowd closer together.”

“Why in the world does your client want to know that density number?”

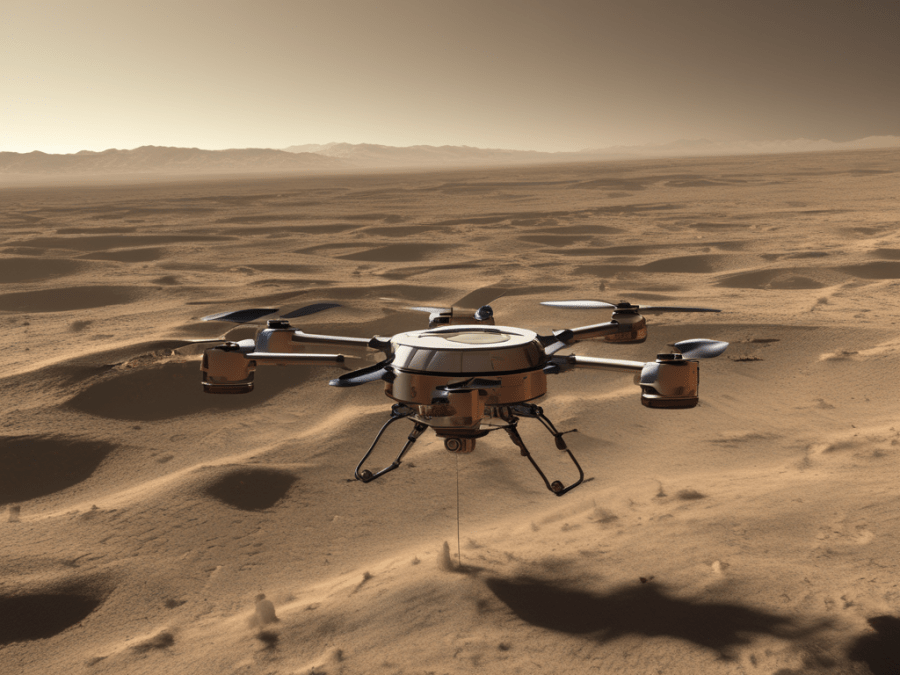

“Clients rarely give me reasons. I suspect this has to do with designing a Titan‑explorer aircraft.”

“Ooo! Wait, what does that have to do with air density?”

“It has to do with how hard the machine has to work to push itself up. It’ll probably have horizontally spinning blades that push the air downwards, like helicopters do. With a setup like that, the lift depends on the blade’s length, how fast it’s spinning, and how dense the air is. If the air is dense, like on Titan, the designers can get the lifting thrust they need with short blades or a slow spin. On Mars the density’s only 2% of Earth’s so Ingenuity‘s rotors were 4 feet across and spun about ten times faster than they’d have to on Earth.”

“What about on our helium‑oxygen Earth?”

“That’s pretty much the same calculation. Give me a sec.” <tapping on Old Reliable’s screen> “Gas density would be a tenth of Earth’s, but a HeO‑copter would have to work against full‑Earth gravity. Huge blades rotating at supersonic speeds. Probably not a practical possibility.”

“Aw.”

“Yeah.”

~ Rich Olcott

Credit: Steve Gribben/NASA/Johns Hopkins APL