A young man’s knock, eager yet a bit hesitant. “Door’s open, Jeremy, c’mon in.”

“Hi, Mr Moire, I’ve got something to show you. It’s from my acheii, my grandfather. He said he didn’t need it any more now he’s retired so he gave it to me. What do you think?”

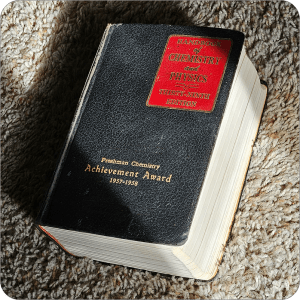

“Wow, the CRC Handbook of Chemistry And Physics, in the old format, not the 8½×11″ monster. An achievement award, too — my congratulations to your grandfather. Let’s see … over 3000 pages, and that real thin paper you can read through. It’s still got the math tables in front — they moved those to an Appendix by the time I bought my copy. Oooh yeah, lots of data in here, probably represents millions of grad student lab hours. Tech staff, too. And then their bosses spent time checking the work before publishing.”

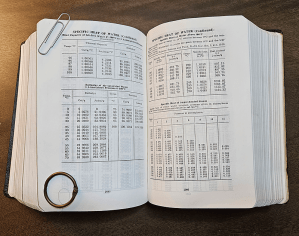

“Acheii said I’d have to learn a lot before I could use it properly. I see lots of words in there I don’t recognize.” <opens book to a random page> “See, five- and six‑figure values for, what’re Specific Heat and Enthalpy?”

“Your grandfather’s absolutely correct. Much of the data’s extremely specialized. Most techs, including me, have a few personal‑favorite sections they use a lot, never touch the rest of the book. These particular pages, for instance, would be gold for a someone who designs or operates steam‑driven equipment.”

“But what do these numbers mean?”

“Specific Heat is the amount of heat energy you need to put into a certain mass of something in order to raise its temperature by a certain amount. In the early days the Brits, the Scots really, defined the British Thermal Unit as the amount of energy it took to raise the temperature of one pound of liquid water by one degree Fahrenheit. You’d calculate a fuel purchase according to how many BTUs you’d need. Science work these days is metric so these pages tabulate Specific Heat for a substance in joules per gram per °C. Tech in the field moves slow so BTUs are still popular inside the USA and outside the lab.”

“But these tables show different numbers for different temperatures and they’re all for water. Why water? Why isn’t the Specific Heat the same number for every temperature?”

“Water’s important because most power systems use steam or liquid water as the working fluid or coolant. Explaining why heat capacity varies with temperature was one of the triumphs of 19th‑century science. Turns out it’s all about how atomic motion but atoms were a controversial topic at the time. Ostwald, for instance—”

“Who?”

“Wilhelm Ostwald, one of science’s Big Names in the late 1800s. Chemistry back then was mostly about natural product analysis and seeing what reacted with what. Ostwald put his resources into studying chemical processes themselves, things like crystallization and catalysis. He’s regarded as the founder of Physical Chemistry. Even though he invented the mole he steadfastly maintained that atoms and molecules were nothing more than diffraction‑generated illusions. He liked a different theory but that one didn’t work out.”

“Too bad for him.”

“Oh, he won the first Nobel Prize in Chemistry so no problem. Anyway, back to Specific Heat. In terms of its molecules, how do you raise something’s temperature?”

“Um, temperature’s average kinetic energy, so I’d just make the molecules move faster.”

“Well said, except in the quantum world there’s another option. The molecules can’t just waggle any which way. There are rules. Different molecules do different waggles. Some kinds of motion take more energy to excite than others do. Rule 1 is that the high‑energy waggles don’t get to play until the low‑energy ones are engaged. Raising the temperature is a matter of activating more of the high‑energy waggles. Make sense?”

“Like electron shells in an atom, right? Filling the lowest‑energy shells first unless a photon supplies more energy?”

“Exactly, except we’re talking atoms moving within a molecule. Smaller energies, by a factor of 100 or more. My point is, the heat capacity of a substance depends on which waggles activate as the temperature rises. We didn’t understand heat capacity until we applied quantum thinking to the waggles.”

“What about ‘Enthalpy’ then?”

~ Rich Olcott