“Whaddaya mean, Sy, if white holes exist? You just told me how they’re in the equations just like black holes.”

“Math gives us only models of reality, Vinnie. Remarkably good models, some of them, but they’re only abstractions. Necessarily they leave out things that might skew math results away from physical results or the other way around. Einstein believed his math properly reflected how the Universe works, but even so, he doubted that black holes could exist. He didn’t think it’d be possible to collect that much mass into such a small space. Two decades after he said that, Oppenheimer figured out how that could happen.”

“Oppenheimer like the A‑bomb movie guy?”

“Same Oppenheimer. He was a major physicist even before they put him in charge of the Manhattan Project. He did a paper in 1939 showing how a star‑collapse could create the most common type of black hole we know of. Twenty‑five years after that the astronomers found proof that black holes exist.”

“Well, if Einstein was wrong about black holes, why wasn’t he wrong about white holes?”

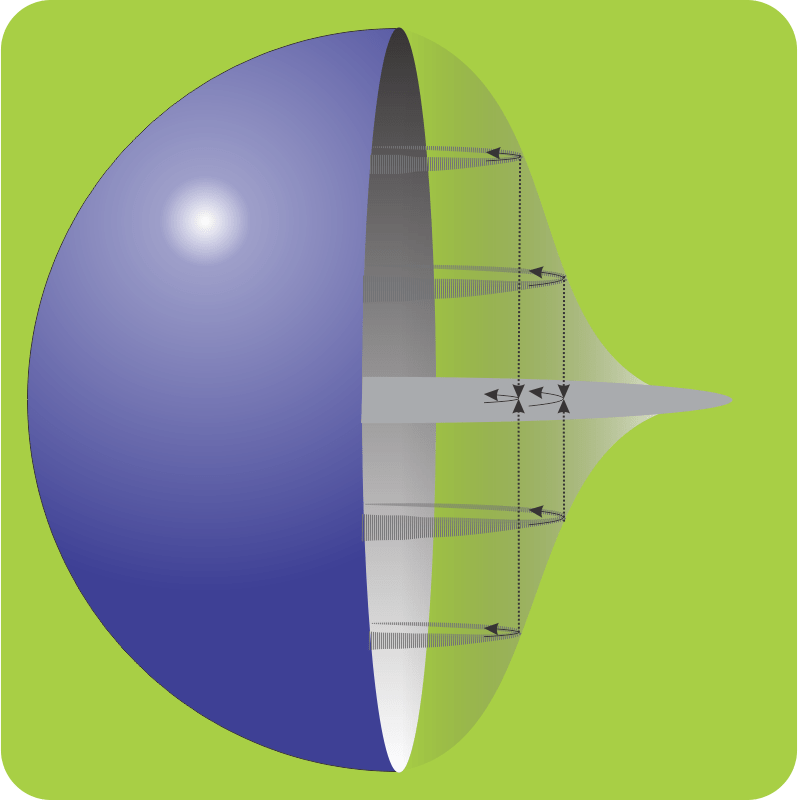

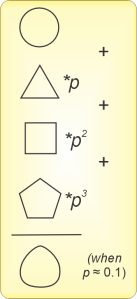

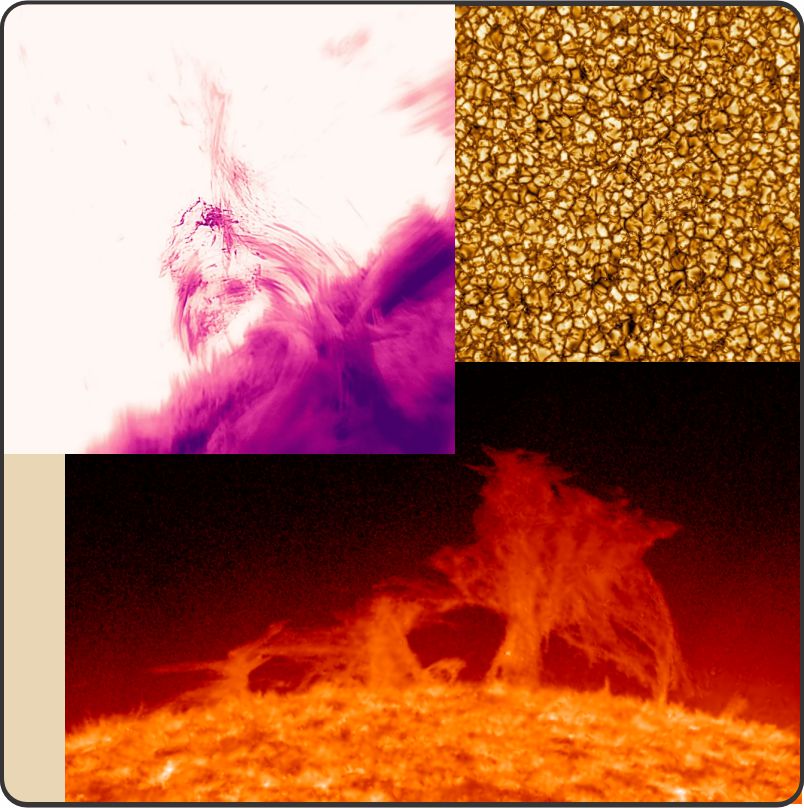

“We need another Oppenheimer to solve that. So far, no‑one has come up with a mechanism that would create a stand‑alone white hole. That level of stress on spacetime requires an enormous amount of mass‑energy in a tiny volume. Whatever does that must somehow do it with a time‑twist opposite to how a black hole is formed. Worse yet, by definition the white hole’s Event Horizon leaks matter and energy. The thing ought to evaporate almost as soon as it’s formed.”

“I heard weaseling. You said, ‘a stand‑alone white hole,’ like there’s maybe another kind. How about that?”

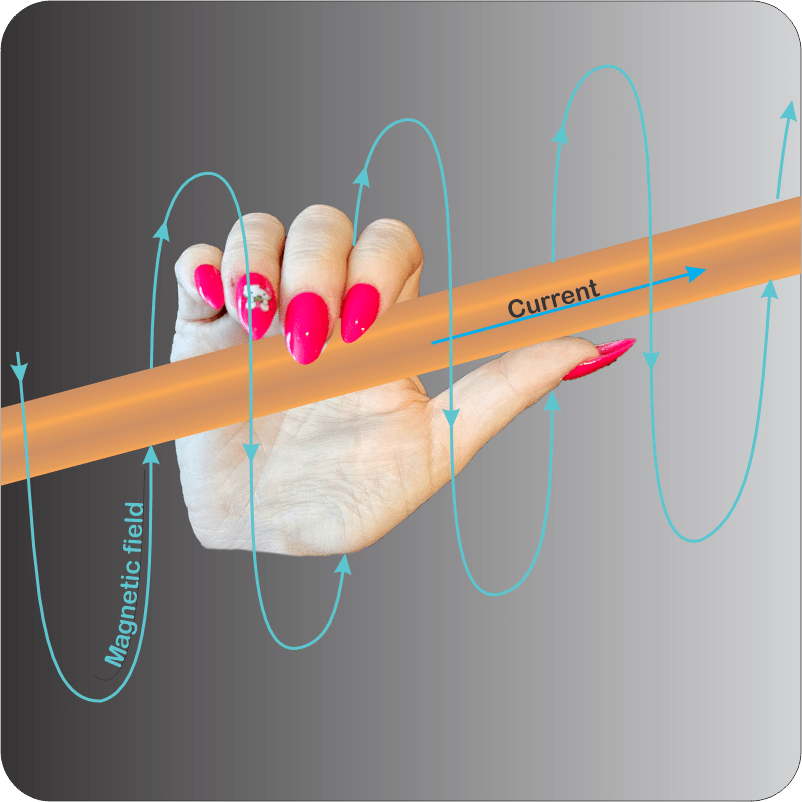

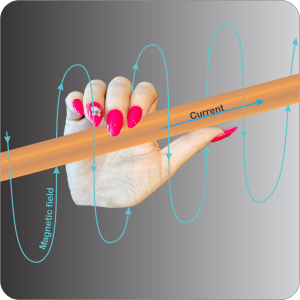

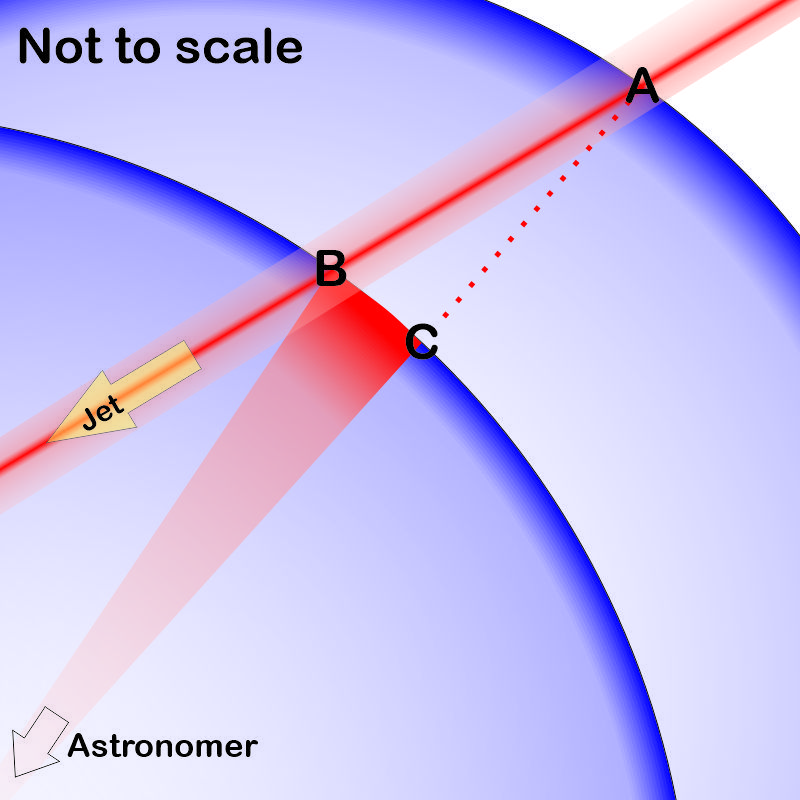

“Could be, maybe not, depending on who’s talking and whether or not they’re accounting for magnetic fields, neutrinos or quantum effects. The discussion generally involves wormholes.”

“Wormholes.”

“Mm-hm. Some cosmologists think that wormholes might bridge between highly stressed points in spacetime. Black hole or white, the stress is what matters. The idea’s been around nearly as long as our modern idea of black holes. No surprise, ‘wormhole’ was coined by John Archibald Wheeler, the same guy who came up with the phrases ‘black hole’ and ‘quantum foam’.”

“Quantum—. Nope, not gonna bite. Get back to white holes.”

“I’m getting there. Anyway, the relativity theory community embraced black holes, white holes and wormholes as primary tools for studying how spacetime works.”

“How’re they gonna do that? That squib Cal showed me said we’ve never seen a white hole.”

“Fair question. Last I heard, the string theory community confidently predicted 10500 different Universes with little hope of narrowing the field. In contrast, relativity theory is firmly constrained by well‑founded math, a century of confirmation from experimental tests and a growing amount of good black hole data. Perfectly good math says that wormholes and white holes could form but only under certain unlikely conditions. Those conditions constrain white holes like Oppenheimer’s conditions constrained forming a stellar‑size black hole.”

“So how do we make one?”

“We don’t. If the Universe can make the right conditions happen somewhere in spacetime, it could contain white holes and maybe a network of wormholes; otherwise, not. Maybe we don’t see them because they’ve all evaporated.”

“I remember reading one time that with quantum, anything not forbidden must happen.”

“Pretty much true, but we’re not talking quantum here. Macro‑scale, some things don’t happen even though they’re not forbidden.”

“Name one.”

“Anti‑matter. The laws of physics work equally well for atoms with positive or negative nuclear charge. We’ve yet to come up with an explanation for why all the nuclear matter we see in the Universe has the positive‑nucleus structure. The mystery’s got me considering a guess for Cathleen’s next Crazy Theories seminar.”

“Oh, yeah? Let’s have it.”

“Strictly confidential, okay?”

“Sure, sure.”

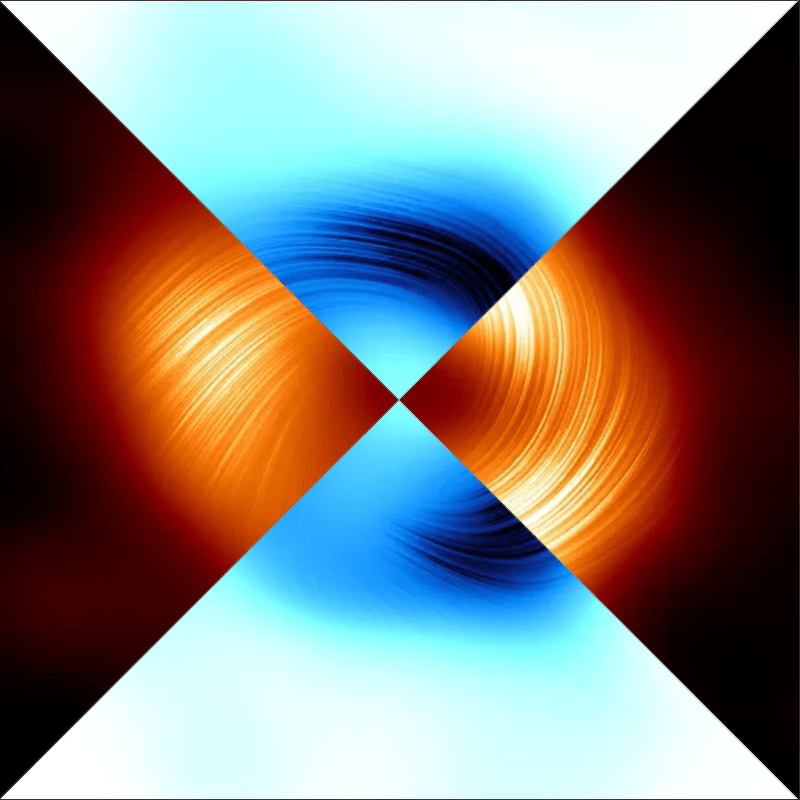

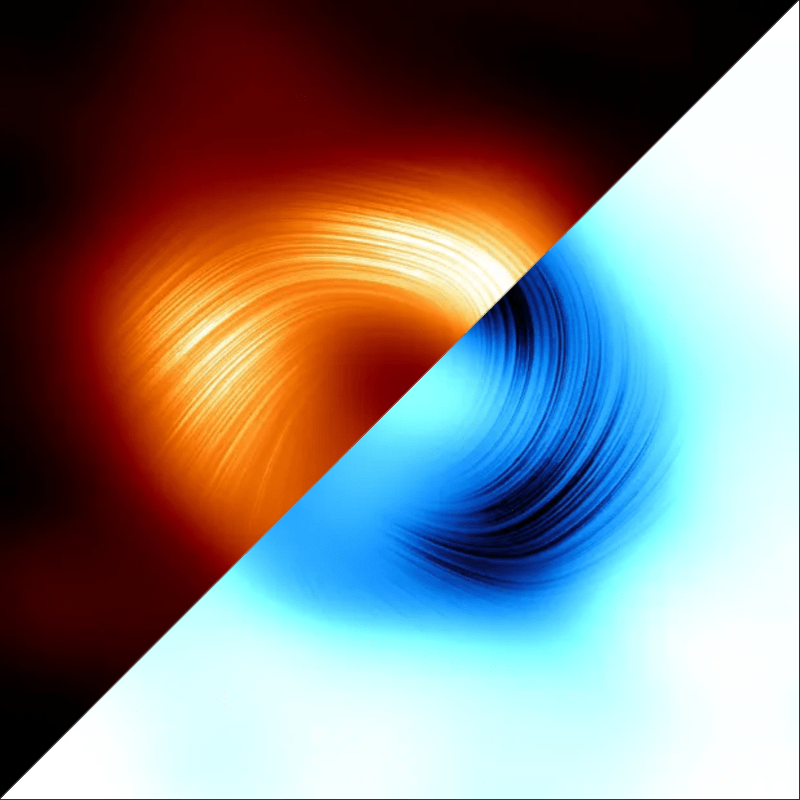

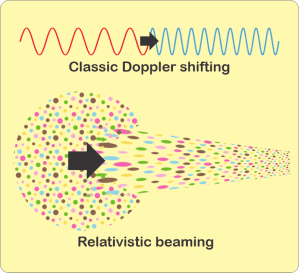

“Suppose the Big Bang’s chaos set up just the right conditions to make a pair of CPT‑twin black holes, expanding in opposite directions along spacetime’s time dimension. Suppose we’re inside one twin. Our time flows normally. If we could see into the other twin, we’d see inside‑out atoms and clocks running backwards. From our perspective the twin would be a white hole.”

“Stay outta that wormhole bridge.”

~ Rich Olcott