The thing about Al’s coffee shop is that there’s generally a good discussion going on, usually about current doings in physics or astronomy. This time it’s in the physicist’s corner but they’re not writing equations on the whiteboard Al put up over there to save on paper napkins. I step over there and grab an empty chair.

The thing about Al’s coffee shop is that there’s generally a good discussion going on, usually about current doings in physics or astronomy. This time it’s in the physicist’s corner but they’re not writing equations on the whiteboard Al put up over there to save on paper napkins. I step over there and grab an empty chair.

“Hi folks, what’s the fuss about?”

“Hi, Mr Moire, we’re arguing about where the outer edge of the Solar System is. I said it’s Pluto’s orbit, like we heard in high school — 325 lightminutes from the Sun.”

The looker beside him pipes up. “Jeremy, that’s just so bogus.” Kid keeps scoring above his level, don’t know how he does it. “Pluto doesn’t do a circular orbit, it’s a narrow ellipse so average distance doesn’t count. Ten percent of the time Pluto’s actually closer to the Sun than Neptune is, and that’s only 250 lightminutes out.”

Then the looker on his other side chimes in. Doing good, kid. “How about the Kuiper Belt? A hundred thousand objects orbiting the Sun out to maybe twice Neptune’s distance, so it’s 500 lightminutes.”

Third looker, across the table. You rock, Jeremy. “Hey, don’t forget the Scattered Disk, where the short-period comets drop in from. That goes out to 100 astronomical units, which’d be … 830 lightminutes.”

One of Cathleen’s Astronomy grad students can’t help diving in despite he’s only standing nearby, not at the table. “Nah, the edge is at the heliopause.”

<several voices> “The what?”

“You know about the solar wind, right, all the neutral and charged particles that get blown out of the Sun? Mass-density-wise it’s a near-vacuum, but it’s not nothing. Neither is the interstellar medium, maybe a few dozen hydrogen and helium atoms per cubic meter but that adds up and they’re not drifting on the same vector the Sun’s using. The heliopause is the boundary where the two flows collide. Particles in the solar wind are hot, relatively speaking, compared to the interstellar medium. Back in 2012, our outbound spacecraft Voyager 1 detected a sharp drop in temperature at 121 astronomical units. You guys are talking lightminutes so that’d be <thumb-pokes his smartphone> how about that? almost exactly 1000 lightminutes out. So there’s your edge.”

Now Al’s into it. “Hold on, how about the Oort Cloud?”

“Mmm, good point. Like this girl said <she bristles at being called ‘girl’>, the short-period comets are pretty much in the ecliptic plane and probably come in from the Scattered Disk. But the long-period comets seem to come in from every direction. That’s why we think the Cloud’s a spherical shell. Furthermore, the far points of their orbits generally lie in the range between 20,000 and 50,000 au’s, though that outer number’s pretty iffy. Call the edge at 40,000 au’s <more thumb-poking> that’d be 332,000 lightminutes, or 3.8 lightdays.”

“Nice job, Jim.” Cathleen speaks up from behind him. “But let’s think a minute about why that top number’s iffy.”

“Umm, because it’s dark out there and we’ve yet to actually see any of those objects?”

“True. At 40,000 au’s the light level is 1/40,000² or 1/1,600,000,000 the sunlight intensity we get on Earth. But there’s another reason. Maybe that ‘spherical shell’ isn’t really a sphere.”

I have to ask. “How could it not be? The Sun’s gravitational field is spherical.”

“Right, but at these distances the Sun’s field is extremely weak. The inverse-square law works for gravity the same way it does for light, so the strength of the Sun’s gravitational field out there is also 1/1,600,000,000 of what keeps the Earth on its orbit. External forces can compete with that.”

“Yeah, I get that, Cathleen, but 3.8 lightdays is … over 400 times closer than the 4½ lightyear distance to the nearest star. The Sun’s field at the Cloud is stronger than Alpha Centauri’s by at least a factor of 400 squared.”

“Think bigger, Sy. The galactic core is 26,000 lightyears away, but it’s the center of 700 billion solar masses. I’ve run the numbers. At Jim’s Oort-Cloud ‘edge’ the Galaxy’s field is 11% as strong as the Sun’s. Tidal forces will pull the outer portion of the Cloud into an egg shape pointed to the center of the Milky Way.”

Jeremy’s agog. “So the edge of the Solar System is 1,000 times further than Pluto? Wow!”

“About.”

“Maybe.”

~~ Rich Olcott

“You’ll have to unravel that for me.”

“You’ll have to unravel that for me.”

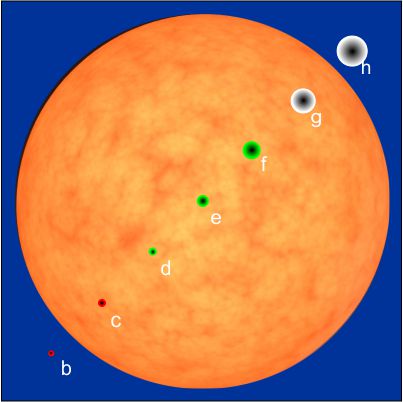

This image is a little better.” (showing me her phone) “This artist at least tried to build in some perspective. Even in this tiny solar system, about 1/500 the radius of ours, the star’s distance to each planet is hundreds to a thousand times the size of the planet. You just can’t show planets AND their orbits together in a linear diagram. Now, think about how small these planets are compared to their sun.”

This image is a little better.” (showing me her phone) “This artist at least tried to build in some perspective. Even in this tiny solar system, about 1/500 the radius of ours, the star’s distance to each planet is hundreds to a thousand times the size of the planet. You just can’t show planets AND their orbits together in a linear diagram. Now, think about how small these planets are compared to their sun.” “How so?”

“How so?”