“Alright, Vinnie, what’s the rest of it?”

“The rest of what, Sy?”

“You wouldn’t have hauled that kid’s toy into Al’s shop here just to play spitballs with it. You’re building up to something and what is it?”

“My black hole hobby, Sy. The things’re just a few miles wide but pack more mass than the Sun. A couple of my magazines say they give off jets top and bottom because of how they spin. That just don’t fit. The stuff ought to come straight out to the sides like the paper wads did.”

“Well, umm… Ah. You know the planet Saturn.”

“Sure.”

“Are its rings part of the planet?”

“No, of course not, they go around it. I even seen an article about how the rings probably came from a couple of collided moons and how water from the Enceladus moon may be part of the outside ring. Only thing Saturn does for the rings is supply gravity to keep ’em there.”

“But our eyes see planet and rings together as a single dot of light in the sky. As far as the rest of the Solar System cares, Saturn consists of that big cloudy ball of hydrogen and the rings and all 82 of its moons, so far. Once you get a few light-seconds away, the whole collection acts as a simple point-source of gravitational attraction.”

“I see where you’re going. You’re gonna say a black hole’s more than just its event horizon and whatever it’s hiding inside there.”

“Yup. That ‘few miles wide’ — I could make a case that you’re off by trillions. A black hole’s a complicated beast when we look at it close up.”

“How can you look at a thing like that close up?”

“Math, mostly, but the observations are getting better. Have you seen the Event Horizon Telescope’s orange ring picture?”

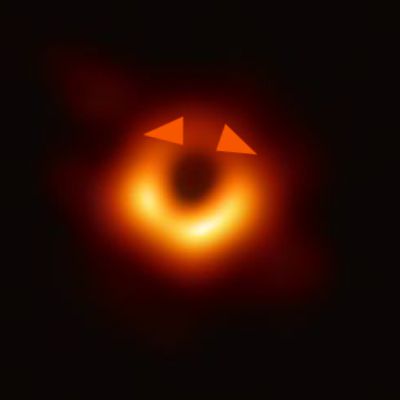

“You mean the one that Al messed with and posted for Hallowe’en? It’s over there behind his cash register. What’s it about, anyway?”

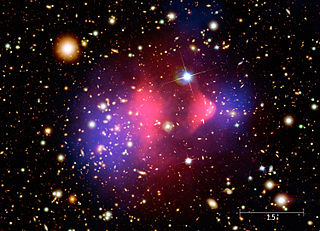

“It’s an image of M87*, the super-massive black hole at the center of the M87 galaxy. Not the event horizon itself, of course, that’s black. The orange portion actually represents millimeter-radio waves that escape from the accretion disk circling the event horizon. The innermost part of the disk is rotating around the hole at near-lightspeed. The arc at the bottom is brighter because that’s the part coming toward us. The photons get a little extra boost from Special Relativity.”

“Frames again?”

“With black holes it’s always frames. You’ll love this. From the shell’s perspective, it spits out the same number of photons per second in every direction. From our perspective, time is stretched on the side rotating away from us so there’s fewer photons per one of our seconds and it’s dimmer. In the same amount of our time the side coming toward us emits more photons so it’s brighter. Neat demonstration, eh?”

“Cute. So the inner black part’s the hole ’cause it can’t give off light, right?”

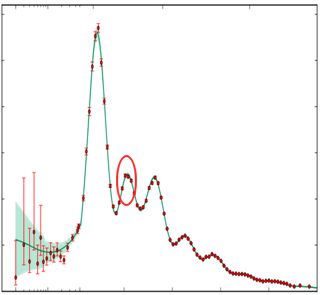

“Not quite. That’s a shadow. Not a shadow of the event horizon itself, mind you, but of the photon sphere. That’s a shell about 1½ times the width of the event horizon. Any photon that passes exactly tangent to the sphere is doomed to orbit there forever. If the photon’s path is the slightest bit inward from that, the poor particle heads inward towards whatever’s in the center. The remaining photons travel paths that look bent to a distant observer, but the point is that they keep going and eventually someone like us could see them.”

“The shadow and the accretion disk, that’s what the EHT saw?”

“Not exactly.”

“There’s more?”

“Yeah. M87* is a spinning black hole, which is more complicated than one that’s sitting still. Wrapped around the photon sphere there’s an ergosphere, as much as three times wider than the event horizon except it’s pumpkin-shaped. The ergosphere’s widest at the rotational equator, but it closes in to meet the event horizon at the two poles. Anything bigger than a photon that crosses its boundary is condemned to join the spin parade, forever rotating in sync with the object’s spin.”

“When are you gonna get to the jets, Sy?”

~~ Rich Olcott

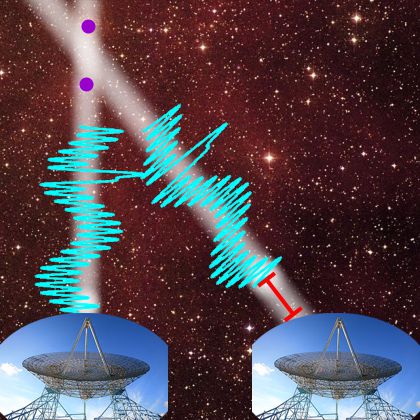

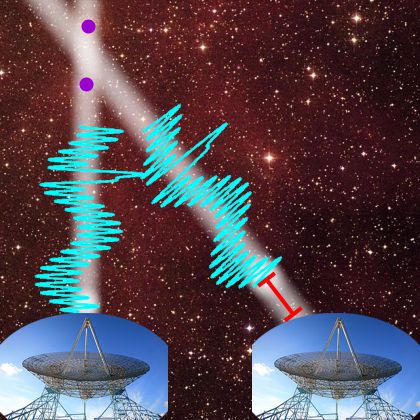

“Gravitational waves are relativity effects and neutrinos are quantum mechanical. Physicists have been struggling for a century to bridge those two domains. Evidence from a three-messenger event could provide the final clues.”

“Gravitational waves are relativity effects and neutrinos are quantum mechanical. Physicists have been struggling for a century to bridge those two domains. Evidence from a three-messenger event could provide the final clues.”