Two teams of scientists, 128 years apart. The first team, two men, got a negative result that shattered a long-standing theory. The second team, a thousand strong, got a positive result that provided final confirmation of another long-standing theory. Both teams used instruments based on the same physical phenomenon. Each team’s innovations created whole new fields of science and technology.

Their common experimental strategy sounds simple enough — compare two beams of light that had traveled along different paths

Their common experimental strategy sounds simple enough — compare two beams of light that had traveled along different paths

Light (preferably nice pure laser light, but Albert Michelson didn’t have a laser when he invented interferometry in 1887) comes in from the source at left and strikes the “beam splitter” — typically, a partially-silvered mirror that reflects half the light and lets the rest through. One beam goes up the y-arm to a mirror that reflects it back down through the half-silvered mirror to the detector. The other beam goes on its own round-trip journey in the x-direction. The detector (Michelson’s eye or a photocell or a fancy-dancy research-quality CCD) registers activity if the waves in the two beams are in step when they hit it. On the other hand, if the waves cancel then there’s only darkness.

Getting the two waves in step requires careful adjustment of the x- and y-mirrors, because the waves are small. The yellow sodium light Michelson used has a peak-to-peak wavelength of 589 nanometers. If he twitched one mirror 0.0003 millimeter away from optimal position the valleys of one wave would cancel the peaks of the other.

So much for principles. The specifics of each team’s device relate to the theory being tested. Michelson was confronting the æther theory, the proposition that if light is a wave then there must be some substance, the æther, that vibrates to carry the wave. We see sunlight and starlight, so the æther must pervade the transparent Universe. The Earth must be plowing through the æther as it circles the Sun. Furthermore, we must move either with or across or against the æther as we and the Earth rotate about its axis. If we’re moving against the æther then lightwave peaks must appear closer together (shorter wavelengths) than if we’re moving with it.

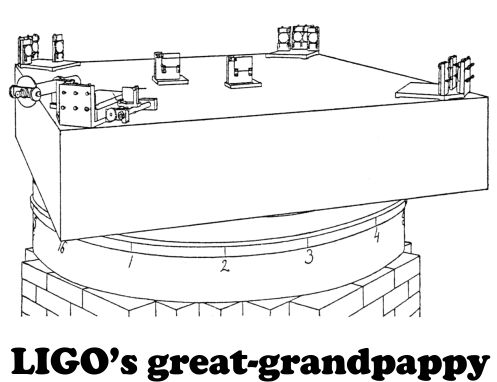

Michelson designed his device to test that chain of logic. His optical apparatus was all firmly bolted to a 4′-square block of stone resting on a wooden ring floating on a pool of mercury. The whole thing could be put into slow rotation to enable comparison of the x– and y-arms at each point of the compass.

According to the æther theory, Michelson and his co-worker Edward Morley should have seen alternating light and dark as he rotated his device. But that’s not what happened. Instead, he saw no significant variation in the optical behavior around the full 360o rotation, whether at noon or at 6:00 PM.

Cross off the æther theory.

Michelson’s strategy depended on light waves getting out of step if something happened to the beams as they traveled through the apparatus. Alternatively, the beams could charge along just fine but something could happen to the apparatus itself. That’s how the LIGO team rolled.

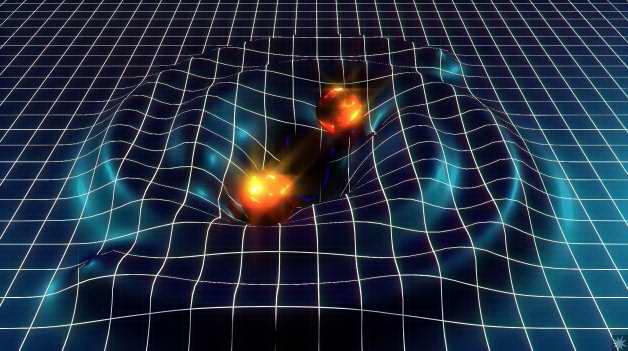

Einstein’s theory of General Relativity predicts that space itself is squeezed and stretched by mass. Miles get shorter near a black hole. Furthermore, if the mass configuration changes, waves of compressive and expansive forces will travel outward at the speed of light. If such a wave were to encounter a suitable interferometer in the right orientation (near-parallel to one arm, near-perpendicular to the other), that would alter the phase relationship between the two beams.

The trick was in the word “suitable.” The expected percentage-wise length change was so small that eLIGO needed 4-kilometer arms to see movement a tiny fraction of a proton’s width. Furthermore, the LIGO designers flipped the classical detection logic. Instead of looking for a darkened beam, they set the beams to cancel at the detector and looked for even a trace of light.

eLIGO saw the light, and confirmed Einstein’s theory.

~~ Rich Olcott

Of all the wave varieties we’re familiar with, gravitational waves are most similar to (NOT identical with!!) sound waves. A sound wave consists of cycles of compression and expansion like you see in this graphic. Those dots could be particles in a gas (classic “sound waves”) or in a liquid (sonar) or neighboring atoms in a solid (a xylophone or marimba).

Of all the wave varieties we’re familiar with, gravitational waves are most similar to (NOT identical with!!) sound waves. A sound wave consists of cycles of compression and expansion like you see in this graphic. Those dots could be particles in a gas (classic “sound waves”) or in a liquid (sonar) or neighboring atoms in a solid (a xylophone or marimba). Einstein noticed that implication of his Theory of General Relativity and in 1916 predicted that the path of starlight would be bent when it passed close to a heavy object like the Sun. The graphic shows a wave front passing through a static gravitational structure. Two points on the front each progress at one graph-paper increment per step. But the increments don’t match so the front as a whole changes direction. Sure enough, three years after Einstein’s prediction, Eddington observed just that effect while watching a total solar eclipse in the South Atlantic.

Einstein noticed that implication of his Theory of General Relativity and in 1916 predicted that the path of starlight would be bent when it passed close to a heavy object like the Sun. The graphic shows a wave front passing through a static gravitational structure. Two points on the front each progress at one graph-paper increment per step. But the increments don’t match so the front as a whole changes direction. Sure enough, three years after Einstein’s prediction, Eddington observed just that effect while watching a total solar eclipse in the South Atlantic. We’re being dynamic here, so the simulation has to include the fact that changes in the mass configuration aren’t felt everywhere instantaneously. Einstein showed that space transmits gravitational waves at the speed of light, so I used a scaled “speed of light” in the calculation. You can see how each of the new features expands outward at a steady rate.

We’re being dynamic here, so the simulation has to include the fact that changes in the mass configuration aren’t felt everywhere instantaneously. Einstein showed that space transmits gravitational waves at the speed of light, so I used a scaled “speed of light” in the calculation. You can see how each of the new features expands outward at a steady rate.

The second question is harder. The best the aLIGO team could do was point to a “banana-shaped region” (their words, not mine) that covers about 1% of the sky. The team marshaled a world-wide collaboration of observatories to scan that area (a huge search field by astronomical standards), looking for electromagnetic activities concurrent with the event they’d seen. Nobody saw any. That was part of the evidence that this collision involved two black holes. (If one or both of the objects had been something other than a black hole, the collision would have given off all kinds of photons.)

The second question is harder. The best the aLIGO team could do was point to a “banana-shaped region” (their words, not mine) that covers about 1% of the sky. The team marshaled a world-wide collaboration of observatories to scan that area (a huge search field by astronomical standards), looking for electromagnetic activities concurrent with the event they’d seen. Nobody saw any. That was part of the evidence that this collision involved two black holes. (If one or both of the objects had been something other than a black hole, the collision would have given off all kinds of photons.) In contrast, a LIGO facility is (roughly speaking) omni-directional. When a LIGO installation senses a gravitational pulse, it could be coming down from the visible sky or up through the Earth from the other hemisphere — one signal doesn’t carry the “which way?” information. The diagram above shows that situation. (The “chevron” is an image of the LIGO in Hanford WA.) Models based on the signal from that pair of 4-km arms can narrow the source field to a “banana-shaped region,” but there’s still that 180o ambiguity.

In contrast, a LIGO facility is (roughly speaking) omni-directional. When a LIGO installation senses a gravitational pulse, it could be coming down from the visible sky or up through the Earth from the other hemisphere — one signal doesn’t carry the “which way?” information. The diagram above shows that situation. (The “chevron” is an image of the LIGO in Hanford WA.) Models based on the signal from that pair of 4-km arms can narrow the source field to a “banana-shaped region,” but there’s still that 180o ambiguity. The great “if only” is that the VIRGO installation in Italy was not recording data when the Hanford WA and Livingston LA saw that September signal. With three recordings to reconcile, the aLIGO+VIRGO combination would have had enough information to slice that banana and localize the event precisely.

The great “if only” is that the VIRGO installation in Italy was not recording data when the Hanford WA and Livingston LA saw that September signal. With three recordings to reconcile, the aLIGO+VIRGO combination would have had enough information to slice that banana and localize the event precisely.

We can investigate things that take longer than an instrument’s characteristic time by making repeated measurements, but we can’t use the instrument to resolve successive events that happen more quickly than that. We also can’t resolve events that take place much closer together than the instrument’s characteristic length.

We can investigate things that take longer than an instrument’s characteristic time by making repeated measurements, but we can’t use the instrument to resolve successive events that happen more quickly than that. We also can’t resolve events that take place much closer together than the instrument’s characteristic length.

A wave happens in a system when a driving force and a restoring force take turns overshooting an equilibrium point AND the away-from-equilibrium-ness gets communicated around the system. The system could be a bunch of springs tied together in a squeaky old bedframe, or labor and capital in an economic system, or the network of water molecules forming the ocean surface, or the fibers in the fabric of space (whatever those turn out to be).

A wave happens in a system when a driving force and a restoring force take turns overshooting an equilibrium point AND the away-from-equilibrium-ness gets communicated around the system. The system could be a bunch of springs tied together in a squeaky old bedframe, or labor and capital in an economic system, or the network of water molecules forming the ocean surface, or the fibers in the fabric of space (whatever those turn out to be). An isolated black hole is surrounded by an intense gravitational field and a corresponding compression of spacetime. A pair of black holes orbiting each other sends out an alternating series of tensions, first high, then extremely high, then high…

An isolated black hole is surrounded by an intense gravitational field and a corresponding compression of spacetime. A pair of black holes orbiting each other sends out an alternating series of tensions, first high, then extremely high, then high…

Almost a century later, James Clerk Maxwell (the bearded fellow at left) wrote down his electromagnetism equations that explain how light works. Half a century later, Einstein did the same for gravity.

Almost a century later, James Clerk Maxwell (the bearded fellow at left) wrote down his electromagnetism equations that explain how light works. Half a century later, Einstein did the same for gravity.

Gravitodynamics is completely unlike electrodynamics. Gravity’s transverse “force” doesn’t act to move a whole mass up and down like Maxwell’s picture at left. Instead, as shown by Einstein’s picture, gravitational waves stretch and compress while leaving the center of mass in place. I put “force” in quotes because what’s being stretched and compressed is space itself. See

Gravitodynamics is completely unlike electrodynamics. Gravity’s transverse “force” doesn’t act to move a whole mass up and down like Maxwell’s picture at left. Instead, as shown by Einstein’s picture, gravitational waves stretch and compress while leaving the center of mass in place. I put “force” in quotes because what’s being stretched and compressed is space itself. See

The experiment consists of shooting laser beams out along both arms, then comparing the returned beams.

The experiment consists of shooting laser beams out along both arms, then comparing the returned beams.