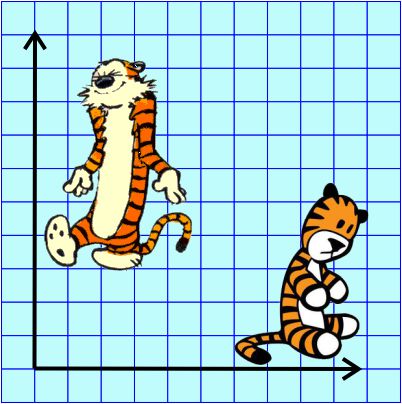

I so miss Calvin and Hobbes, the wondrous, joyful comic strip that cartoonist Bill Watterson gave us between 1985 and 1995. Hobbes was a stuffed toy tiger — except that 6-year-old Calvin saw him as a walking, talking man-sized tiger with a sarcastic sense of humor.

I so miss Calvin and Hobbes, the wondrous, joyful comic strip that cartoonist Bill Watterson gave us between 1985 and 1995. Hobbes was a stuffed toy tiger — except that 6-year-old Calvin saw him as a walking, talking man-sized tiger with a sarcastic sense of humor.

So many things in life and physics are like Hobbes — they depend on how you look at them. As we saw earlier, a fictitious force disappears when viewed from the right frame of reference. There’s that particle/wave duality thing that Duc de Broglie “blessed” us with. And polarized light.

In an earlier post I mentioned that light is polar, in the sense that a single photon’s electric field acts to vibrate an electron (pole-to-pole) within a single plane.

In this video, orange, green and blue electromagnetic fields shine in from one side of the box onto its floor. Each color’s field is polar because it “lives” in only one plane. However, the beam as a whole is unpolarized because different components of the total field direct recipient electrons into different planes giving zero net polarization. The Sun and most other familiar light sources emit unpolarized light.

In this video, orange, green and blue electromagnetic fields shine in from one side of the box onto its floor. Each color’s field is polar because it “lives” in only one plane. However, the beam as a whole is unpolarized because different components of the total field direct recipient electrons into different planes giving zero net polarization. The Sun and most other familiar light sources emit unpolarized light.

When sunlight bounces at a low angle off a surface, say paint on a car body or water at the beach, energy in a field that is directed perpendicular to the surface is absorbed and turned into heat energy. (Yeah, I’m skipping over a semester’s-worth of Optics class, but bear with me.) In the video, that’s the orange wave.

At the same time, fields parallel to the surface are reflected. That’s what happens to the blue wave.

Suppose a wave is somewhere in between parallel and perpendicular, like the green wave. No surprise, the vertical part of its energy is absorbed and the horizontal part adds to the reflection intensity. That’s why the video shows the outgoing blue wave with a wider swing than its incoming precursor had.

The net effect of all this is that low-angle reflected light is polarized and generally more intense than the incident light that induced it. We call that “glare.” Polarizing sunglasses can help by selectively blocking horizontally-polarized electric fields reflected from water, streets, and that *@%*# car in front of me.

Things can get more complicated. The waves in the first video are all in synch — their peaks and valleys match up (mostly). But suppose an x-directed field and a y-directed field are headed along the same course. Depending on how they match up, the two can combine to produce a field driving electrons along the x-direction, the y-direction, or in clockwise or counterclockwise circles. Check the red line in this video — RHC and LHC depict the circularly polarized light that sci-fi writers sometimes invoke when they need a gimmick.

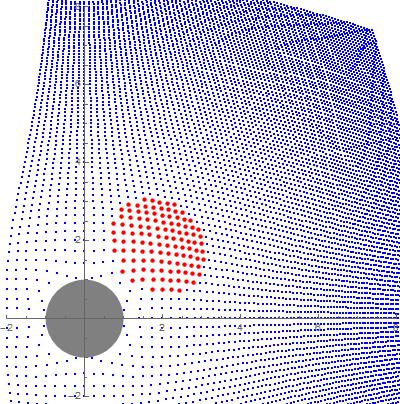

Physicists have several ways to describe such a situation mathematically. I’ve already used the first, which goes back 380 years to René Descartes and the Cartesian x, y,… coordinate system he planted the seed for. We’ve become so familiar with it that reading a graph is like reading words. Sometimes easier.

In Cartesian coordinates we write x– and y-coordinates as separate functions of time t:

x = f1(t)

y = f2(t)

where each f could be something like 0.7·t2-1.3·t+π/4 or whatever. Then for each t-value we graph a point where the vertical line at the calculated x intersects the horizontal line at the calculated y.

But we can simplify that with a couple of conventions. Write √(-1) as i, and say that i-numbers run along the y-axis. With those conventions we can write our two functions in a single line:

x + i y = f1(t) + i f2(t)

One line is better than two when you’re trying to keep track of a big calculation.

But people have a long-running hang-up that’s part theory and part psychology. When Bombelli introduced these complex numbers back in the 16th century, mathematicians complained that you can’t pile up i thingies. Descartes and others simply couldn’t accept the notion, called the numbers “imaginary,” and the term stuck.

Which is why Hobbes the way Calvin sees him is on the imaginary axis.

~~ Rich Olcott

Suppose you had a graph with one axis for counting animal things and another for counting vegetable things. Animals added to animals makes more animals; vegetables added to vegetables makes more vegetables. If you’ve got a chicken, two potatoes and an onion, and you share with your buddy who has a couple of carrots, some green beans and another onion, you’re on your way to a nice chicken stew.

Suppose you had a graph with one axis for counting animal things and another for counting vegetable things. Animals added to animals makes more animals; vegetables added to vegetables makes more vegetables. If you’ve got a chicken, two potatoes and an onion, and you share with your buddy who has a couple of carrots, some green beans and another onion, you’re on your way to a nice chicken stew.

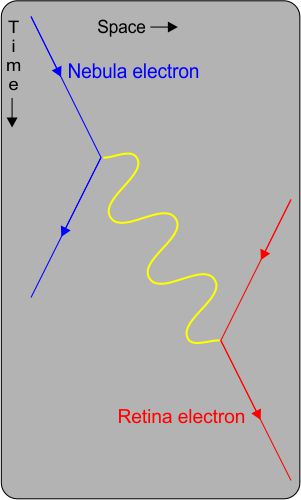

Here we have a Feynman diagram, named for the Nobel-winning (1965) physicist who invented it and much else. The diagram plots out the transaction we just discussed. Not a conventional x-y plot, it shows Space, Time and particles. To the left, that far-away electron emits a photon signified by the yellow wiggly line. The photon has momentum so the electron must recoil away from it.

Here we have a Feynman diagram, named for the Nobel-winning (1965) physicist who invented it and much else. The diagram plots out the transaction we just discussed. Not a conventional x-y plot, it shows Space, Time and particles. To the left, that far-away electron emits a photon signified by the yellow wiggly line. The photon has momentum so the electron must recoil away from it.

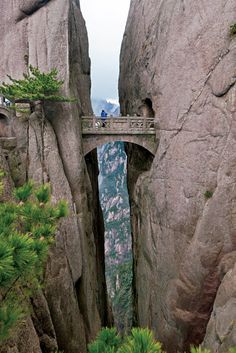

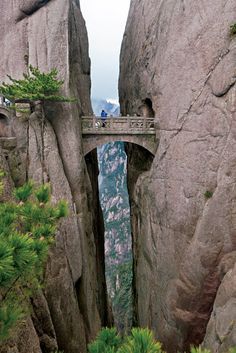

See that little guy on the bridge, suspended halfway between all the way down and all the way up? That’s us on the cosmic size scale.

See that little guy on the bridge, suspended halfway between all the way down and all the way up? That’s us on the cosmic size scale. So that’s the size range of the Universe, from 1.6×10-35 up to 2.6×1026 meters. What’s a reasonable way to fix a half-way mark between them?

So that’s the size range of the Universe, from 1.6×10-35 up to 2.6×1026 meters. What’s a reasonable way to fix a half-way mark between them?

It all started with Newton’s mechanics, his study of how objects affect the motion of other objects. His vocabulary list included words like force, momentum, velocity, acceleration, mass, …, all concepts that seem familiar to us but which Newton either originated or fundamentally re-defined. As time went on, other thinkers added more terms like power, energy and action.

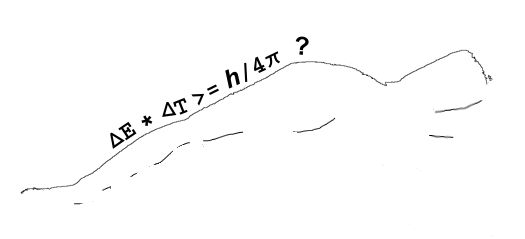

It all started with Newton’s mechanics, his study of how objects affect the motion of other objects. His vocabulary list included words like force, momentum, velocity, acceleration, mass, …, all concepts that seem familiar to us but which Newton either originated or fundamentally re-defined. As time went on, other thinkers added more terms like power, energy and action. There is another way to get the same dimension expression but things aren’t not as nice there as they look at first glance. Action is given by the amount of energy expended in a given time interval, times the length of that interval. If you take the product of energy and time the dimensions work out as (ML2/T2)*T = ML2/T, just like Heisenberg’s Area.

There is another way to get the same dimension expression but things aren’t not as nice there as they look at first glance. Action is given by the amount of energy expended in a given time interval, times the length of that interval. If you take the product of energy and time the dimensions work out as (ML2/T2)*T = ML2/T, just like Heisenberg’s Area.