Vinnie does this thing when he’s near the end of his meal. He mashes his pizza crumbs and mozzarella dribbles into marbles he rolls around on his plate. Mostly on his plate. Eddie hates it when one escapes onto his floor. “Vinnie, you lose one more of those, you’ll be paying extra.”

“Aw, c’mon, Eddie, I’m your best customer.”

“Maybe, but there’ll be a surcharge for havin’ to mop extra around your table.”

Always the compromiser, I break in. “How about you put on less sauce, Eddie?”

Both give me looks you wouldn’t want.

”Lower the quality of my product??!?”

”Adjust perfection??!?”

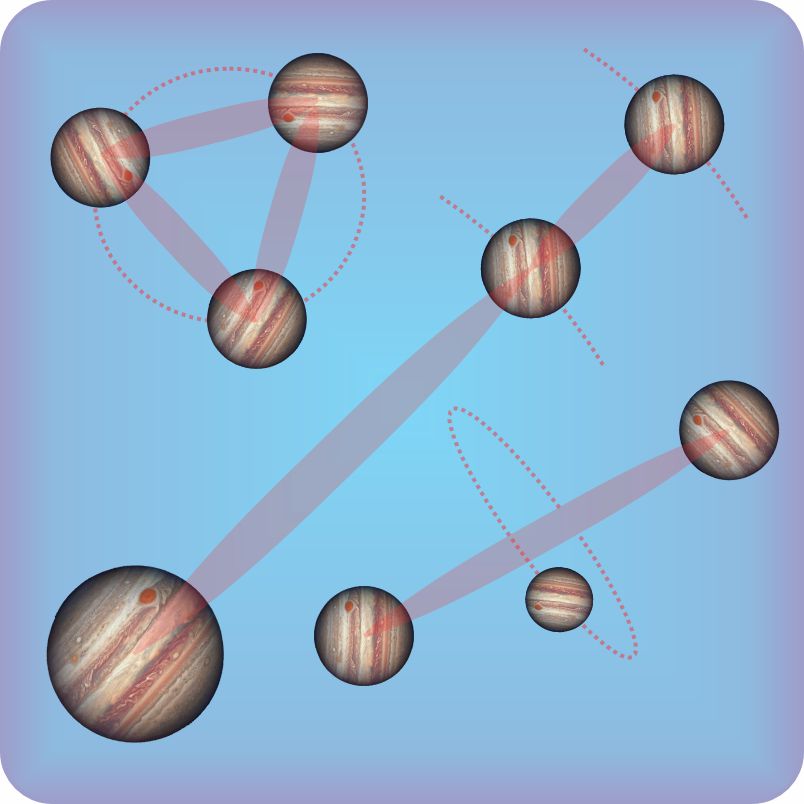

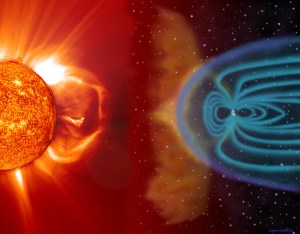

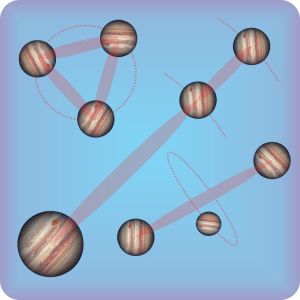

“Looks like we’ve got a three‑body problem here.” Blank looks all around. “You two were just about to go at it until I put in my piece and suddenly you’re on the same side. Two‑way interaction predictable results, three‑way interaction hard to figure. Like when Newton calculated celestial orbits to confirm his Laws of Gravity and Motion. They worked fine for the Earth going around the Sun, not so good for the Moon going around the Earth. The Sun pulls on the Moon just enough to play hob with his two‑body Earth‑Moon predictions.”

“Newton again. So how did he solve it?”

“He didn’t, not exactly anyway.”

“Not smart enough?”

“No, Eddie, plenty smart. Later mathematicians have proven that the three‑body problem simply doesn’t have a general exact solution.”

“Ah-hah, Sy, I heard weaseling — general?”

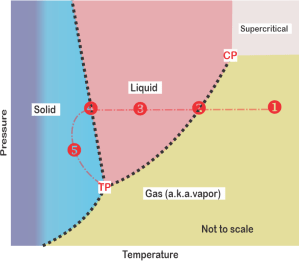

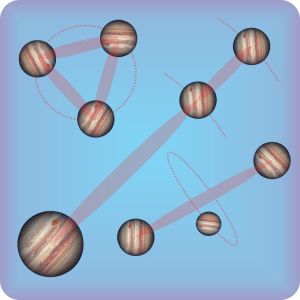

“Alright, Vinnie, there are some stable special cases. Three bodies at relative rest in an equilateral triangle; certain straight‑line configurations; two biggies circling each other and a third, smaller one in a distant orbit around the other two’s center of gravity. There are other specials but none stable in the sense that they wouldn’t be disrupted by a wobbly gravity field from a nearby star or the host galaxy.”

to the three-body problem

by MaxwellMolecule,

licensed under CC ASA 4.0

“So if NASA’s mission planners are looking at a four‑body Sun‑Jupiter‑Europa‑Juno situation, what’re they gonna do? ‘Give up’ ain’t an option.”

“Sure not. There’s a grand strategy with variations. The oldest variation goes back to before the Egyptian builders and everybody still uses it. Vinnie, when you fly a client to Tokyo, do you target a specific landing runway?”

“Naw, I aim for Japan, contact ATC Narita when I get close and they vector me in to wherever they want me to land.”

“How about you, Eddie? How do you get that exquisite balance in your flavoring?”

“Ain’t easy, Sy. Every batch of each herb is different — when it was picked, how it was stored, even the weather while it was growing. I start with an average mix which is usually close, then add a pinch of this and a little of that until it’s right.”

“For both of you, the critical word there was ‘close’. Call it in‑flight course adjustments, call it pinch‑and‑taste, everybody uses the ‘tweaking’ strategy. It’s a matter of skill and intuition, usually hard to generalize and even harder to teach in a systematic fashion. Engineers do it a lot, theoretical physicists work hard to avoid it.”

“What’ve they got that’s better?”

” ‘Better’ depends on your criteria. The method’s called ‘perturbation theory’ and strictly speaking, you can only use it for certain kinds of problems. Newton’s, for instance.”

“Good ol’ Newton.”

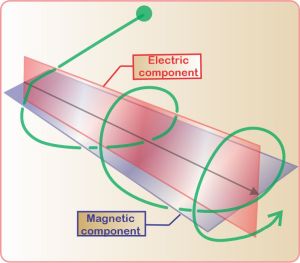

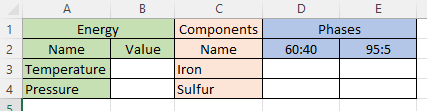

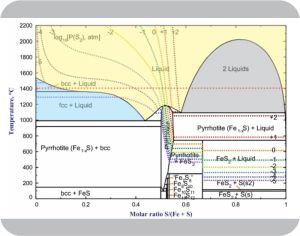

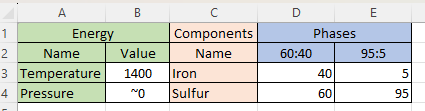

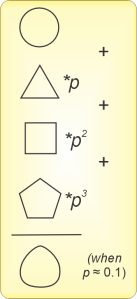

“Of course. Newton’s calculations almost matched Kepler’s planetary observations, but finagling the ‘not quite’ gave Newton headaches. More than 150 years passed before Laplace and others figured out how to treat a distant object as a perturbation of an ideal two‑body situation. It starts with calculating the system’s total energy, which wasn’t properly defined in Newton’s day. A perturbation factor p controls the third body’s contribution. The energy expression lets you calculate the orbits, but they’re the sum of terms containing powers of p. If p=0.1, p2=0.01, p3=0.001 and so on. If p isn’t zero but is still small enough, the p3 term and maybe even the p2 term are too small to bother with.”

“I’ll stick with pinch‑and‑taste.”

“Me and NASA’ll keep course‑correcting.”

~ Rich Olcott