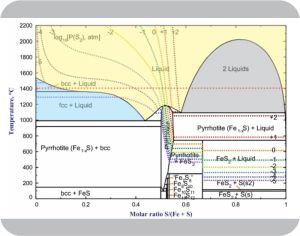

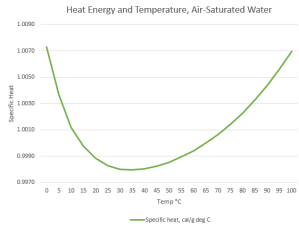

Vinnie’s been eavesdropping (he’s good at that). “You guys said that these researcher teams looked at how iron and sulfur play together at a bunch of different temperature, pressures and blend ratios. That’s a pretty nice chart, the one that shows mix and temperature. Got one for pressure, like the near‑vacuum over Loki’s lava lake on Io?”

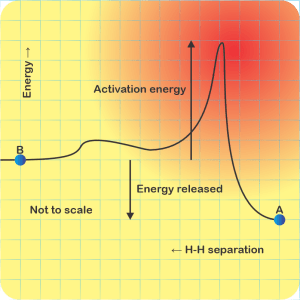

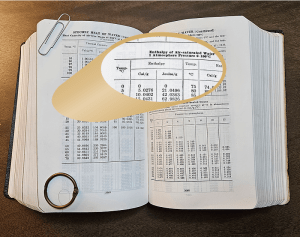

“Not to my knowledge, Vinnie. Of course I’m a lab chemist, not a theoretical astrogeochemist. Kareem’s phase diagram is for normal atmospheric pressure. I’d bet virtually all related lab work extends from there to the higher pressures down toward Earth’s center. Million‑atmosphere experiments are difficult — even just trying to figure out whether a microgram sample’s phase in a diamond anvil cell is solid or liquid. Right, Kareem?”

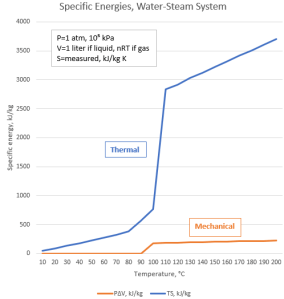

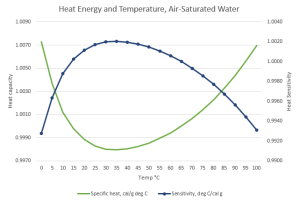

“Mm‑hm, but the computer work’s hard, too, Susan. We’ve got several suites of software packages for modeling whatever set of pressure-temperature-composition parameters you like. The problem is that the software needs relevant thermodynamic data from the pressure and temperature extremes like from those tough‑to‑do experiments. There’s been surprises when a material exhibited new phases no‑one had ever seen or measured before. Water’s common, right, but just within the past decade we may have discovered five new high‑pressure forms of ice.”

“May have?”

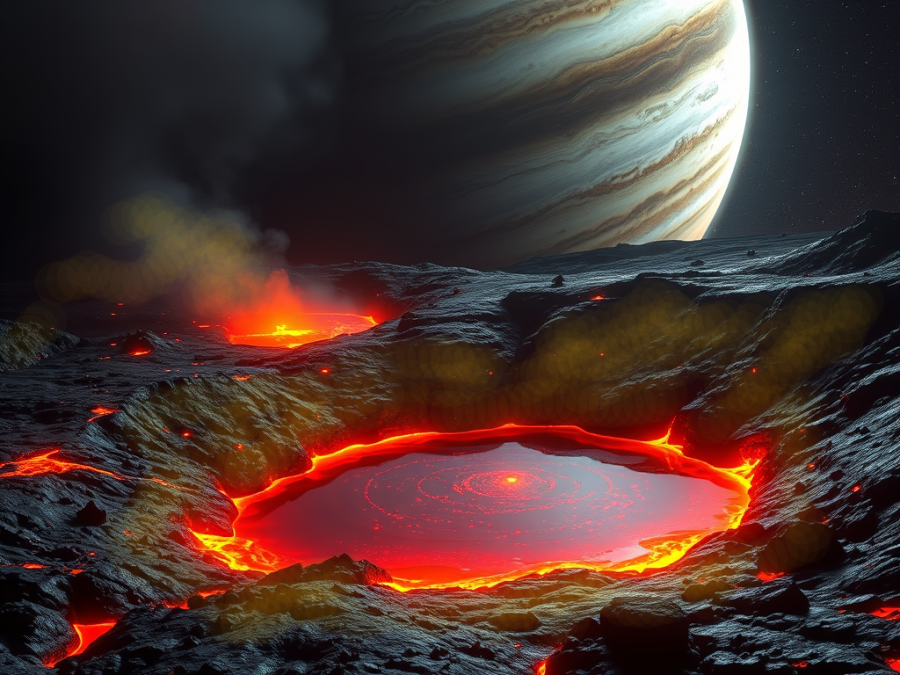

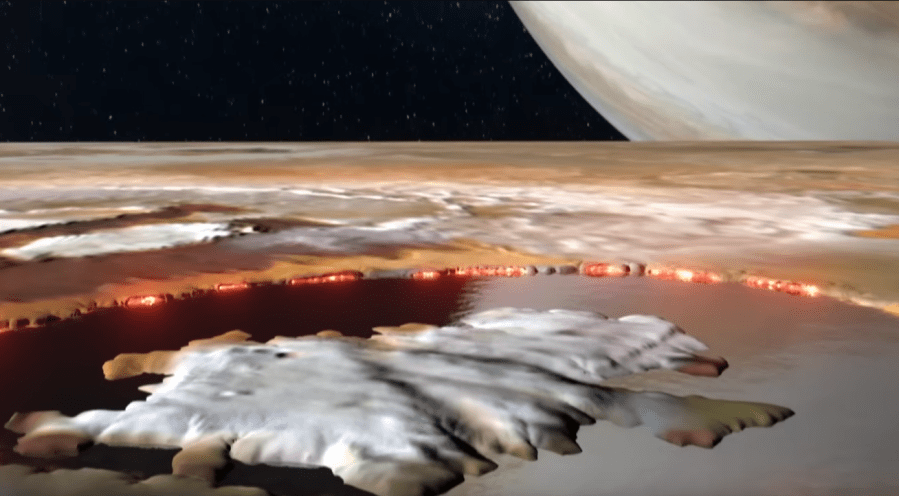

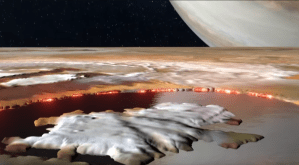

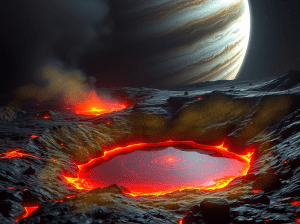

a lava lake on Jupiter’s moon Io

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS

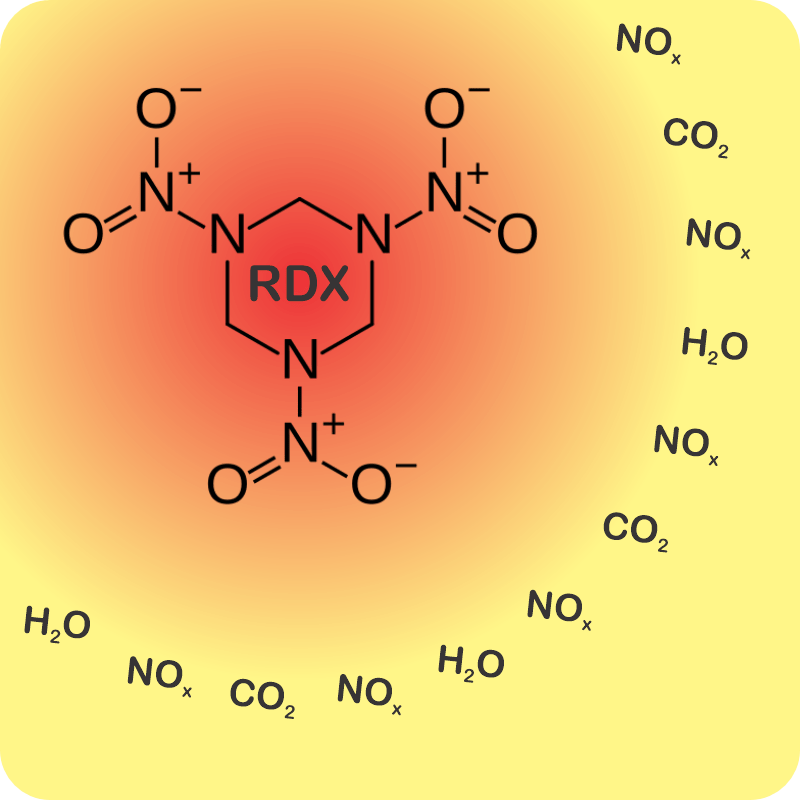

“The academics are still arguing about each of them. Setting aside that problem, modeling Io’s low‑pressure environment is a challenge because it’s not a lab situation. Consider Cal’s pretty picture there. See those glowing patches all around the lava lake’s shore? They’re real. Juno‘s JIRAM instrument detected hot rings around Loki and nearly a dozen of its cousins. Such continual heat release tells us the lakes are being stirred or pumped somehow. Whatever delivers heat to the shore also must deliver some kind of hot iron‑sulfur phase to the cooler surface. That’ll separate out like slag in a steel furnace.”

“It’s worse than that, Kareem. Sulfur’s just under oxygen in the periodic table, so like oxygen it’s willing to be gaseous S2. Churned‑up hot lava can’t help but give off sulfur vapor that the models will have to account for.”

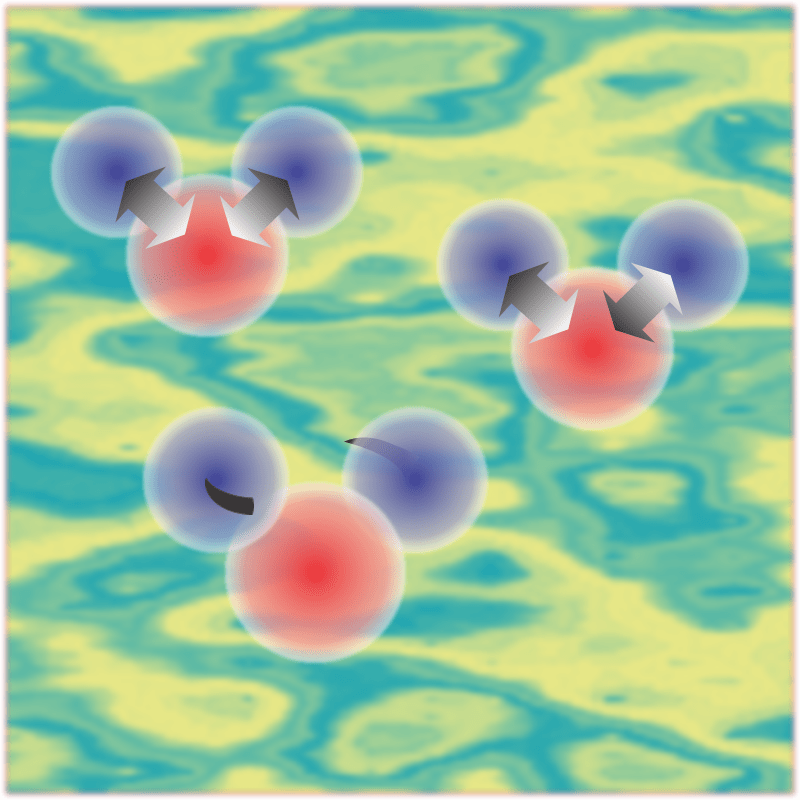

I cut in. “It’s worse than that, Susan. I’ve written about Jupiter’s crazy magnetic field, off‑center and the strongest of any planet. Io’s the closest large moon to Jupiter, deep in that field. Sulfur molecules run away from a magnetic field; free sulfur atoms dive into one. Either way, if you’re some sulfur species floating above a lava lake when Jupiter’s field sweeps past, you won’t be hanging around that lake for long. Most likely, you’ll join the parade across the Io‑to‑Jupiter flux tube bridge.”

Susan chortles. “Obviously not an equilibrium. It’s a steady state!”

“Huh?” from everyone. Cal gives her, “Steady state?”

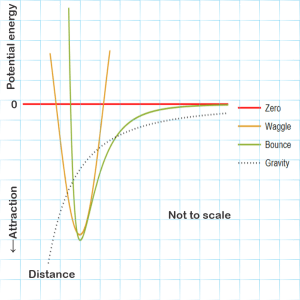

“Chemical equilibrium is when a reaction and its reverse go at equal rates, right, so the overall composition doesn’t change. That’s the opposite of situations where there’s a forward reaction but for some reason the products don’t get a chance to back‑react. Classic case is precipitation, say when you bubble smelly H2S gas through a solution that may contain lead ions. If there’s lead in there you get a black lead sulfide sediment that’s so insoluble there’s no re‑dissolve. Picture an industrial vat with lead‑contaminated waste water coming in one pipe and H2S gas bubbling in from another. If you adjust the flow rates right, all the lead’s stripped out, there’s no residual stink in the effluent water and the net content of the vat doesn’t change. That’s a steady state.”

“What’s that got to do with Loki’s lake?”

“Sulfur vapors come off it and those glowing rings tell us it’s giving off heat. It’s just sitting there not getting hotter and probably not changing much in composition. There’s got to be sulfur and heat inflow to make up for the outflow. The lake’s in a steady state, not an equilibrium. Thermodynamic calculations like Gibbs’ phase rule can’t tell you anything about the lake’s composition because that depends on the kinetics — how fast magma comes in, how fast heat and sulfur go out. Kareem’s phase diagram just doesn’t apply.”

~ Rich Olcott