A familiar shadow loomed in from the hallway.

“C’mon in, Vinnie, the door’s open.”

“I brought some sandwiches, Sy.”

“Oh, thanks, Vinnie.”

“Don’t mention it. An’ I got another LIGO issue.”

“Yeah?”

“Ohh, yeah. Now we got that frame thing settled, how does it apply to what you wrote back when? I got a copy here…”

The local speed of light (miles per second) in a vacuum is constant. Where space is compressed, the miles per second don’t change but the miles get smaller. The light wave slows down relative to the uncompressed laboratory reference frame.

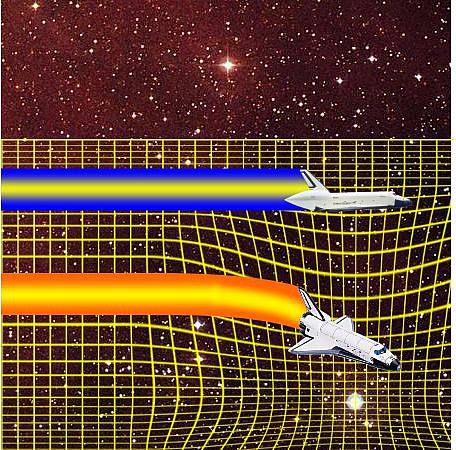

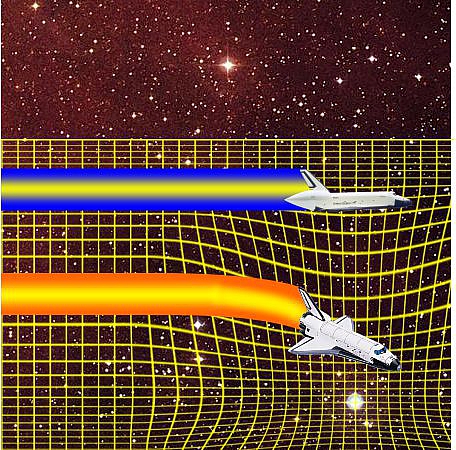

“Ah, I admit I was a bit sloppy there. Tell you what, let’s pretend we’re piloting a pair of space shuttles following separate navigation beams that are straight because that’s what light rays do. So long as we each fly a straight line at constant speed we’re both using the same inertial frame, right?”

“Sure.”

“And if a gravity field suddenly bent your beam to one side, you’d think you’re still flying straight but I’d think you’re headed on a new course, right?”

“Yeah, because now we’d have different inertial frames. I’d think your heading has changed, too.”

“So what does the guy running the beams see?”

“Oh, ground-pounders got their own inertial frame, don’t they? Uhh… He sees me veer off and you stay steady ’cause the gravity field bent only my beam.”

“Right — my shuttle and the earth-bound observer share the same inertial frame, for a while.”

“A while?”

“Forever if the Earth were flat because I’d be flying straight and level, no threat to the shared frame. But the Earth’s not flat. If I want to stay at constant altitude then I’ve got to follow the curve of the surface rather than follow the light beam straight out into space. As soon as I vector downwards I have a different frame than the guy on the ground because he sees I’m not in straight-line motion.”

“It’s starting to get complicated.”

“No worries, this is as bad as it gets. Now, let’s get back to square one and we’re flying along and this time the gravity field compresses your space instead of bending it. What happens? What do you experience?”

“Uhh… I don’t think I’d feel any difference. I’m compressed, the air molecules I breath are compressed, everything gets smaller to scale.”

“Yup. Now what do I see? Do we still have the same inertial frame?”

“Wow. Lessee… I’m still on the beam so no change in direction. Ah! But if my space is compressed, from your frame my miles look shorter. If I keep going the same miles per second by my measure, then you’ll see my speed drop off.”

“Good thinking but there’s even more to it. Einstein showed that space compression and time dilation are two sides of the same phenomenon. When I look at you from my inertial frame, your miles appear to get shorter AND your seconds appear to get longer.”

“My miles per second slow way down from the double whammy, then?”

“Yup, but only in my frame and that other guy’s down on the ground, not in yours.”

“Wait! If my space is compressed, what happens to the space around what got compressed? Doesn’t the compression immediately suck in the rest of the Universe?”

“Einstein’s got that covered, too. He showed that gravity doesn’t act instantaneously. Whenever your space gets compressed, the nearby space stretches to compensate (as seen from an independent frame, of course). The edge of the stretching spreads out at the speed of light. But the stretch deformation gets less intense as it spreads out because it’s only offsetting a limited local compression.”

“OK, let’s get back to LIGO. We got a laser beam going back and forth along each of two perpendicular arms, and that famous gravitational wave hits one arm broadside and the other arm cross-wise. You gonna tell me that’s the same set-up as me and you in the two shuttles?”

“That’s what I’m going to tell you.”

“And the guy on the ground is…”

“The laboratory inertial reference.”

“Eat your sandwich, I gotta think about this.”

(sounds of departing footsteps and closing door)

“Don’t mention it.”

~~ Rich Olcott

“Does the Moon go around the Earth or does the Earth go around the Moon?”

“Does the Moon go around the Earth or does the Earth go around the Moon?”

“Squeeze in two sides, pop out the other two, eh?”

“Squeeze in two sides, pop out the other two, eh?”

But there are other accelerations that aren’t so easily accounted for. Ever ride in a car going around a curve and find yourself almost flung out of your seat? This little guy wasn’t wearing his seat belt and look what happened. The car accelerated because changing direction is an acceleration due to a lateral force. But the guy followed Newton’s First Law and just kept going in a straight line. Did he accelerate?

But there are other accelerations that aren’t so easily accounted for. Ever ride in a car going around a curve and find yourself almost flung out of your seat? This little guy wasn’t wearing his seat belt and look what happened. The car accelerated because changing direction is an acceleration due to a lateral force. But the guy followed Newton’s First Law and just kept going in a straight line. Did he accelerate? Suppose you’re investigating an object’s motion that appears to arise from a new force you’d like to dub “heterofugal.” If you can find a different frame of reference (one not attached to the object) or otherwise explain the motion without invoking the “new force,” then heterofugalism is a fictitious force.

Suppose you’re investigating an object’s motion that appears to arise from a new force you’d like to dub “heterofugal.” If you can find a different frame of reference (one not attached to the object) or otherwise explain the motion without invoking the “new force,” then heterofugalism is a fictitious force.

Sure enough, that’s a straight line (see the chart). Reminds me of how Newton’s Law of Gravity is valid

Sure enough, that’s a straight line (see the chart). Reminds me of how Newton’s Law of Gravity is valid

Gargh, proto-humanity’s foremost physicist 2.5 million years ago, opened a practical investigation into how motion works. “I throw rock, hit food beast, beast fall down yes. Beast stay down no. Need better rock.” For the next couple million years, we put quite a lot of effort into making better rocks and better ways to throw them. Less effort went into understanding throwing.

Gargh, proto-humanity’s foremost physicist 2.5 million years ago, opened a practical investigation into how motion works. “I throw rock, hit food beast, beast fall down yes. Beast stay down no. Need better rock.” For the next couple million years, we put quite a lot of effort into making better rocks and better ways to throw them. Less effort went into understanding throwing. Aristotle wasn’t satisfied with anything so unsystematic. He was just full of theories, many of which got in each other’s way. One theory was that things want to go where they’re comfortable because of what they’re made of — stones, for instance, are made of earth so naturally they try to get back home and that’s why we see them fall downwards (no concrete linkage, so it’s still AAAD).

Aristotle wasn’t satisfied with anything so unsystematic. He was just full of theories, many of which got in each other’s way. One theory was that things want to go where they’re comfortable because of what they’re made of — stones, for instance, are made of earth so naturally they try to get back home and that’s why we see them fall downwards (no concrete linkage, so it’s still AAAD).

I was only 10 years old but already had Space Fever thanks to Chesley Bonestell’s artwork in Collier’s and Life magazines. I eagerly joined the the movie theater ticket line to see George Pal’s Destination Moon. I loved the Woody Woodpecker cartoon (it’s 12 minutes into the

I was only 10 years old but already had Space Fever thanks to Chesley Bonestell’s artwork in Collier’s and Life magazines. I eagerly joined the the movie theater ticket line to see George Pal’s Destination Moon. I loved the Woody Woodpecker cartoon (it’s 12 minutes into the