We’re both leery of the Acme Building’s elevators after escaping from one, so Vinnie and I take the stairs down to Pizza Eddie’s. “Faster, Sy, that order we called in will be cold when we get there.”

“Maybe not, Vinnie. Depends on his backlog.”

“Hey, before all this started, we were talking about the improved time standard and you said something about optical clockwork. I gather it’s got something to do with lasers and such.”

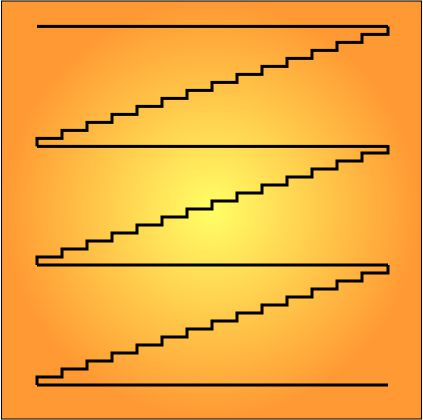

“It sure does. Boils down to Science preferring count-based units over ratios because they’re more precise. If you count something twice you should get exactly the same answer each time; if you’re measuring a ratio against a ruler or something, duplicate measurements might not agree. For instance, you can probably tell me how many steps there are between floors — “

“Fourteen”

“— more precisely than you can tell me the floor-to-floor height in feet or meters. And more accurately, too.”

“How can it be more accurate? I’ve got a range-finder gadget that reads out to a tenth of an inch. Or a millimeter if you set the switch for that.”

“Because that reading is subject to all sorts of potential errors — maybe you’re pointing it at an angle, or its temperature calibration is off, or you’re moving and there’s a Doppler effect. It may give you exactly the same reading twice in a row —”

“I always measure twice before I cut once.”

“Of course you do. My point is, that device might give you very precise but inaccurate answers that are way off. You’d have to calibrate its readings against a trustworthy standard to be sure.”

“Suppose my range-finder’s as precise as my step-counting. How can step-counting be better?”

“Because the step is defined as the measurement unit. There’s no calibration issues or instrumental drift or ‘it depends on how good the carpenter was,’ a step is a step. Step counting is accurate by definition. Nearly all our conventional units of measurement have some built-in ‘‘it depends’ factors that drive the measurement folks crazy. Like the foot, for instance — every time a new king came to power, his foot became the new standard and every wood and cloth merchant in the kingdom had to revise their inventory listings.”

“OK, so that’s basically why the time-measurement people wanted to get away from that ‘a second is a fraction of a day back when‘ definition — too many ‘it depends’ factors and they wanted something they could count. Got it. So back in what, 1967? they switched to a time standard where they could count waves and they went to the ‘a second is so many waves‘ thing. I also got that their first shot was to use microwaves ’cause that’s what they could count. But that was half-a-century ago. Haven’t they moved up the spectrum since then, say to visible light?”

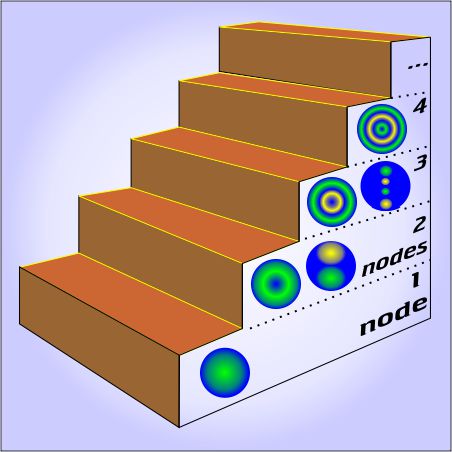

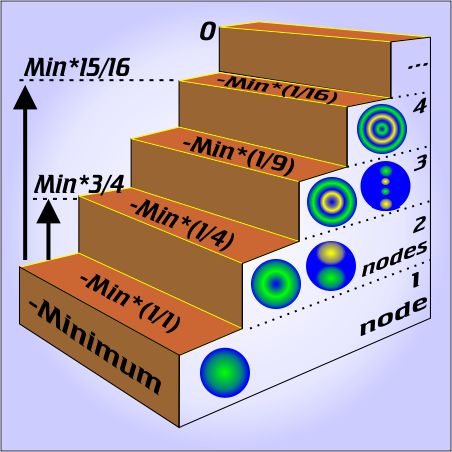

“Not quite. They had to get tricky. Think about it. Yellow-orange light’s wavelength is about 600 nanometers or 600×10-9 meters. Divide that by the speed of light, 3×108 meters/second, and you get that each wave whizzes by in only 2×10-15 seconds. Our electronics still can’t count that fast, but we can cheat. Uhhh … which would be easier to answer — how many floors in this building or how many steps?”

“Floors, of course, there’s a lot fewer of them.”

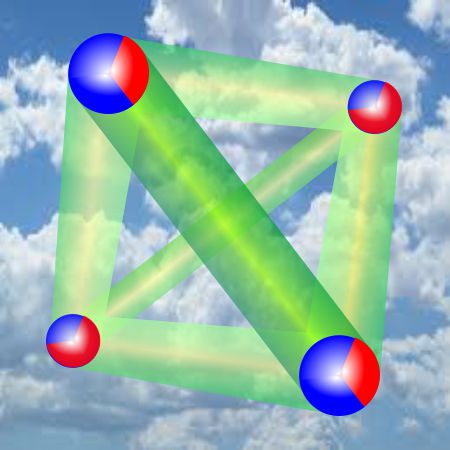

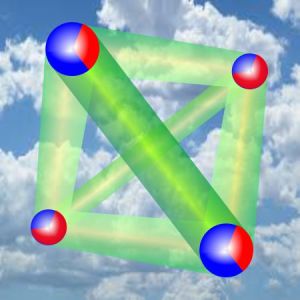

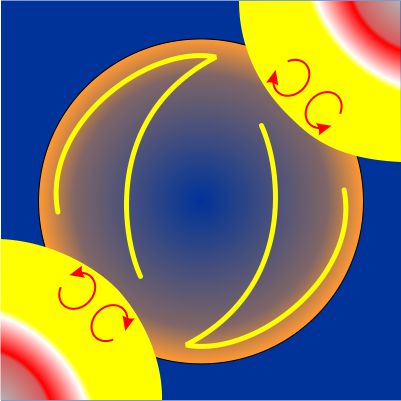

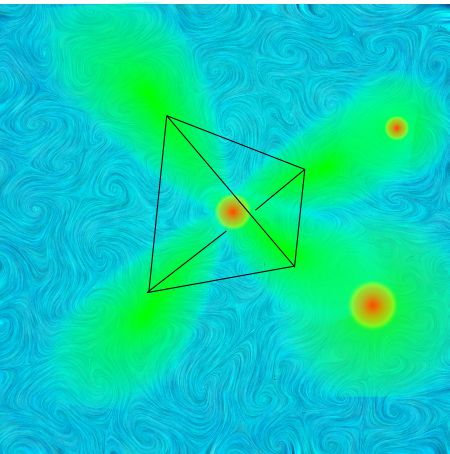

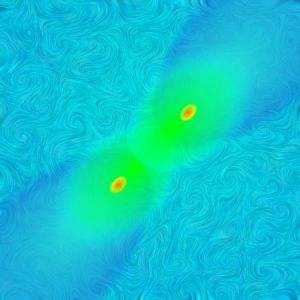

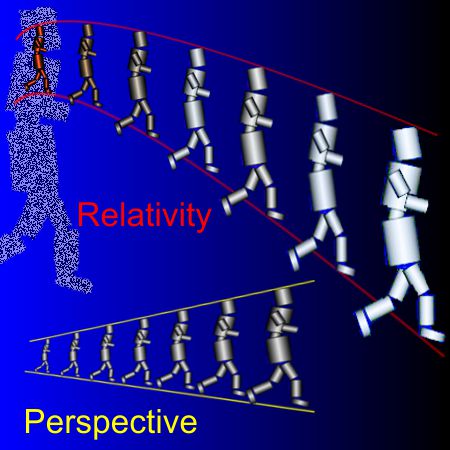

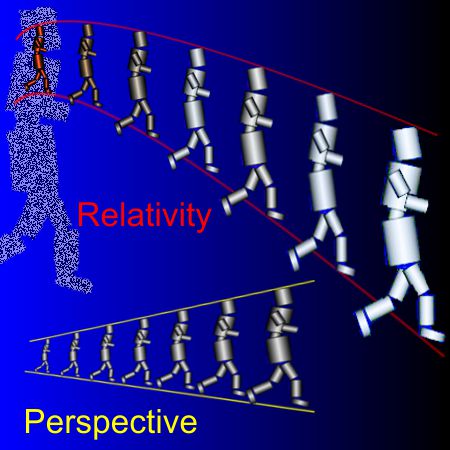

“But the step count would track the floor count, regular as clockwork, because an exact number of steps separates each pair of floors. If you know one count, arithmetic tells you the other. The same logic can work with lightwaves. Soon after the engineers developed mode-locking theory and a few tricks like frequency combs, they figured out ways to stabilize a maser by mode-locking it to a laser. It’s like gearing down a once-a-second pendulum to regulate the hour-hand of a clock, so of course they called it optical clockwork even though there’s no gears.”

“Maser?”

“A maser does microwaves the way a laser does lightwaves. Every tick from a cesium-based maser is about 47,000 ticks from a strontium-based laser. Mode-lock them together and your clock’s good within a few seconds over the age of the Universe.”

“Hiya, Eddie.”

“Hiya, Vinnie. Perfect timing. Those pizzas you called for, they’re just comin’ outta the oven.”

~~ Rich Olcott

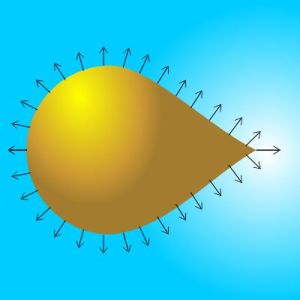

With my finger I draw in the frost on his gelato cabinet. “Imagine this is a brass ball, except I’ve pulled one side of it out to a cone. Someone’s loaded it up with extra electrons so it’s carrying a high negative charge.”

With my finger I draw in the frost on his gelato cabinet. “Imagine this is a brass ball, except I’ve pulled one side of it out to a cone. Someone’s loaded it up with extra electrons so it’s carrying a high negative charge.”

“Hey, that’s the

“Hey, that’s the

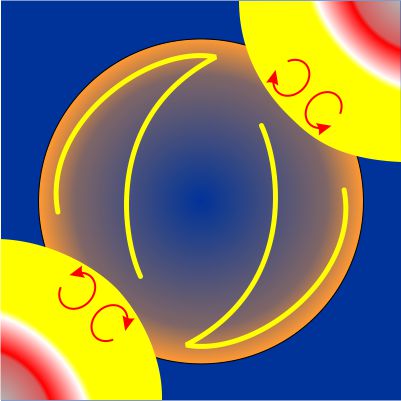

“But GR’s not the only player. Special Relativity’s in there, too.”

“But GR’s not the only player. Special Relativity’s in there, too.”