There’s something peculiar in this earlier post where I embroidered on Einstein’s gambit in his epic battle with Bohr. Here, I’ll self-plagiarize it for you…

Consider some nebula a million light-years away. A million years ago an electron wobbled in the nebular cloud, generating a spherical electromagnetic wave that expanded at light-speed throughout the Universe.

Last night you got a glimpse of the nebula when that lightwave encountered a retinal cell in your eye. Instantly, all of the wave’s energy, acting as a photon, energized a single electron in your retina. That particular lightwave ceased to be active elsewhere in your eye or anywhere else on that million-light-year spherical shell.

Suppose that photon was yellow light, smack in the middle of the optical spectrum. Its wavelength, about 580nm, says that the single far-away electron gave its spherical wave about 2.1eV (3.4×10-19 joules) of energy. By the time it hit your eye that energy was spread over an area of a trillion square lightyears. Your retinal cell’s cross-section is about 3 square micrometers so the cell can intercept only a teeny fraction of the wavefront. Multiplying the wave’s energy by that fraction, I calculated that the cell should be able to collect only 10-75 joules. You’d get that amount of energy from a 100W yellow light bulb that flashed for 10-73 seconds. Like you’d notice.

But that microminiscule blink isn’t what you saw. You saw one full photon-worth of yellow light, all 2.1eV of it, with no dilution by expansion. Water waves sure don’t work that way, thank Heavens, or we’d be tsunami’d several times a day by earthquakes occurring near some ocean somewhere.

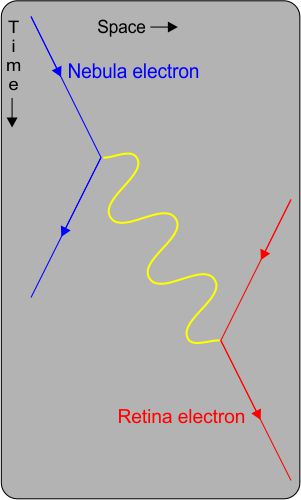

Here we have a Feynman diagram, named for the Nobel-winning (1965) physicist who invented it and much else. The diagram plots out the transaction we just discussed. Not a conventional x-y plot, it shows Space, Time and particles. To the left, that far-away electron emits a photon signified by the yellow wiggly line. The photon has momentum so the electron must recoil away from it.

Here we have a Feynman diagram, named for the Nobel-winning (1965) physicist who invented it and much else. The diagram plots out the transaction we just discussed. Not a conventional x-y plot, it shows Space, Time and particles. To the left, that far-away electron emits a photon signified by the yellow wiggly line. The photon has momentum so the electron must recoil away from it.

The photon proceeds on its million-lightyear journey across the diagram. When it encounters that electron in your eye, the photon is immediately and completely converted to electron energy and momentum.

Here’s the thing. This megayear Feynman diagram and the numbers behind it are identical to what you’d draw for the same kind of yellow-light electron-photon-electron interaction but across just a one-millimeter gap.

It’s an essential part of the quantum formalism — the amount of energy in a given transition is independent of the mechanical details (what the electrons were doing when the photon was emitted/absorbed, the photon’s route and trip time, which other atoms are in either neighborhood, etc.). All that matters is the system’s starting and ending states. (In fact, some complicated but legitimate Feynman diagrams let intermediate particles travel faster than lightspeed if they disappear before the process completes. Hint.)

Because they don’t share a common history our nebular and retinal electrons are not entangled by the usual definition. Nonetheless, like entanglement this transaction has Action-At-A-Distance stickers all over it. First, and this was Einstein’s objection, the entire wave function disappears from everywhere in the Universe the instant its energy is delivered to a specific location. Second, the Feynman calculation describes a time-independent, distance-independent connection between two permanently isolated particles. Kinda romantic, maybe, but it’d be a boring movie plot.

As Einstein maintained, quantum mechanics is inherently non-local. In QM change at one location is instantaneously reflected in change elsewhere as if two remote thingies are parts of one thingy whose left hand always knows what its right hand is doing.

Bohr didn’t care but Einstein did because relativity theory is based on geometry which is all about location. In relativity, change here can influence what happens there only by way of light or gravitational waves that travel at lightspeed.

In his book Spooky Action At A Distance, George Musser describes several non-quantum examples of non-locality. In each case, there’s no signal transmission but somehow there’s a remote status change anyway. We don’t (yet) know a good mechanism for making that happen.

It all suggests two speed limits, one for light and matter and the other for Einstein’s “deeper reality” beneath quantum mechanics.

~~ Rich Olcott

Gargh, proto-humanity’s foremost physicist 2.5 million years ago, opened a practical investigation into how motion works. “I throw rock, hit food beast, beast fall down yes. Beast stay down no. Need better rock.” For the next couple million years, we put quite a lot of effort into making better rocks and better ways to throw them. Less effort went into understanding throwing.

Gargh, proto-humanity’s foremost physicist 2.5 million years ago, opened a practical investigation into how motion works. “I throw rock, hit food beast, beast fall down yes. Beast stay down no. Need better rock.” For the next couple million years, we put quite a lot of effort into making better rocks and better ways to throw them. Less effort went into understanding throwing. Aristotle wasn’t satisfied with anything so unsystematic. He was just full of theories, many of which got in each other’s way. One theory was that things want to go where they’re comfortable because of what they’re made of — stones, for instance, are made of earth so naturally they try to get back home and that’s why we see them fall downwards (no concrete linkage, so it’s still AAAD).

Aristotle wasn’t satisfied with anything so unsystematic. He was just full of theories, many of which got in each other’s way. One theory was that things want to go where they’re comfortable because of what they’re made of — stones, for instance, are made of earth so naturally they try to get back home and that’s why we see them fall downwards (no concrete linkage, so it’s still AAAD).

It would have been awesome to watch Dragon Princes in battle (from a safe hiding place), but I’d almost rather have witnessed “The Tussles in Brussels,” the two most prominent confrontations between Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr.

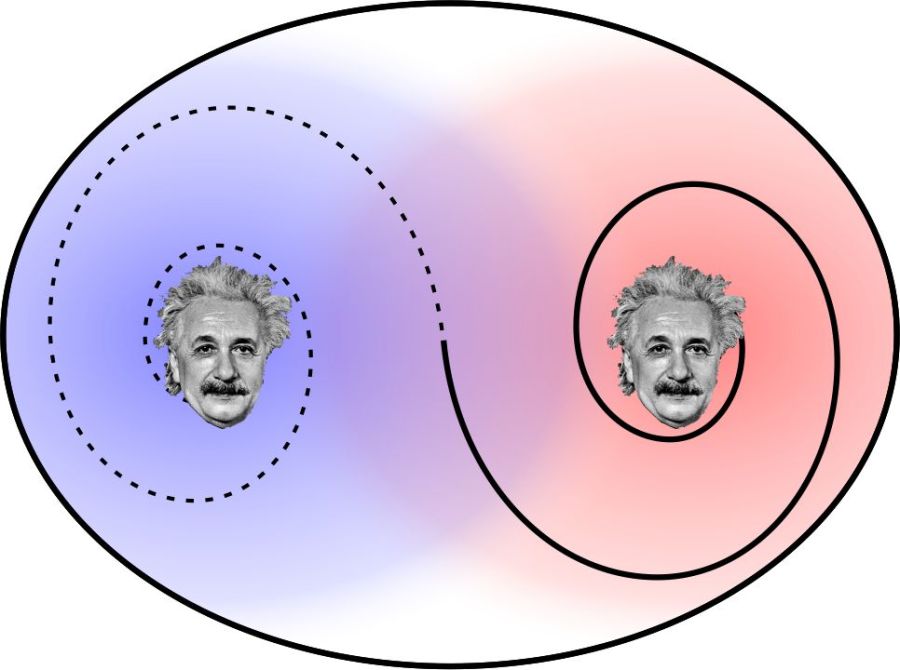

It would have been awesome to watch Dragon Princes in battle (from a safe hiding place), but I’d almost rather have witnessed “The Tussles in Brussels,” the two most prominent confrontations between Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr. Like Newton, Einstein was a particle guy. He based his famous thought experiments on what his intuition told him about how particles would behave in a given situation. That intuition and that orientation led him to paradoxes such as entanglement, the

Like Newton, Einstein was a particle guy. He based his famous thought experiments on what his intuition told him about how particles would behave in a given situation. That intuition and that orientation led him to paradoxes such as entanglement, the  Bohr was six years younger than Einstein. Both Bohr and Einstein had attained Directorship of an Institute at age 35, but Bohr’s has his name on it. He started out as a particle guy — his first splash was a trio of papers that treated the hydrogen atom like a one-planet solar system. But that model ran into serious difficulties for many-electron atoms so Bohr switched his allegiance from particles to Schrödinger’s wave theory. Solve a Schrödinger equation and you can calculate statistics like

Bohr was six years younger than Einstein. Both Bohr and Einstein had attained Directorship of an Institute at age 35, but Bohr’s has his name on it. He started out as a particle guy — his first splash was a trio of papers that treated the hydrogen atom like a one-planet solar system. But that model ran into serious difficulties for many-electron atoms so Bohr switched his allegiance from particles to Schrödinger’s wave theory. Solve a Schrödinger equation and you can calculate statistics like  Here’s where Ludwig Wittgenstein may have come into the picture. Wittgenstein is famous for his telegraphically opaque writing style and for the fact that he spent much of his later life disagreeing with his earlier writings. His 1921 book, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (in German despite the Latin title) was a primary impetus to the Logical Positivist school of philosophy. I’m stripping out much detail here, but the book’s long-lasting impact on QM may have come from its Proposition 7: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.“

Here’s where Ludwig Wittgenstein may have come into the picture. Wittgenstein is famous for his telegraphically opaque writing style and for the fact that he spent much of his later life disagreeing with his earlier writings. His 1921 book, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (in German despite the Latin title) was a primary impetus to the Logical Positivist school of philosophy. I’m stripping out much detail here, but the book’s long-lasting impact on QM may have come from its Proposition 7: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.“

Information transfer at infinite speed? Of course not, because neither hungry person knows what’s in either box until they open one or until they exchange information. Even Skype operates at light-speed (or slower).

Information transfer at infinite speed? Of course not, because neither hungry person knows what’s in either box until they open one or until they exchange information. Even Skype operates at light-speed (or slower).

Suppose you’re playing goalie in an inverse tennis game. There’s a player in each service box. Your job is to run the net line using your rackets to prevent either player from getting a ball into the opposing half-court. Basically, you want the ball’s locations to look like the single-node yellow shape up above. You’ll have to work hard to do that.

Suppose you’re playing goalie in an inverse tennis game. There’s a player in each service box. Your job is to run the net line using your rackets to prevent either player from getting a ball into the opposing half-court. Basically, you want the ball’s locations to look like the single-node yellow shape up above. You’ll have to work hard to do that.

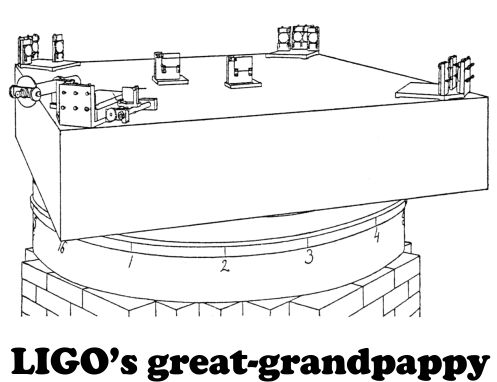

Their common experimental strategy sounds simple enough — compare two beams of light that had traveled along different paths

Their common experimental strategy sounds simple enough — compare two beams of light that had traveled along different paths

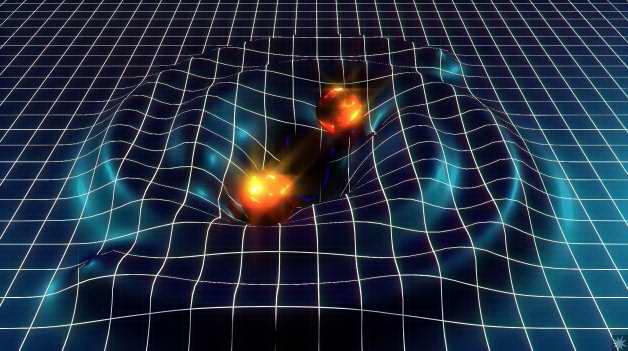

Of all the wave varieties we’re familiar with, gravitational waves are most similar to (NOT identical with!!) sound waves. A sound wave consists of cycles of compression and expansion like you see in this graphic. Those dots could be particles in a gas (classic “sound waves”) or in a liquid (sonar) or neighboring atoms in a solid (a xylophone or marimba).

Of all the wave varieties we’re familiar with, gravitational waves are most similar to (NOT identical with!!) sound waves. A sound wave consists of cycles of compression and expansion like you see in this graphic. Those dots could be particles in a gas (classic “sound waves”) or in a liquid (sonar) or neighboring atoms in a solid (a xylophone or marimba). Einstein noticed that implication of his Theory of General Relativity and in 1916 predicted that the path of starlight would be bent when it passed close to a heavy object like the Sun. The graphic shows a wave front passing through a static gravitational structure. Two points on the front each progress at one graph-paper increment per step. But the increments don’t match so the front as a whole changes direction. Sure enough, three years after Einstein’s prediction, Eddington observed just that effect while watching a total solar eclipse in the South Atlantic.

Einstein noticed that implication of his Theory of General Relativity and in 1916 predicted that the path of starlight would be bent when it passed close to a heavy object like the Sun. The graphic shows a wave front passing through a static gravitational structure. Two points on the front each progress at one graph-paper increment per step. But the increments don’t match so the front as a whole changes direction. Sure enough, three years after Einstein’s prediction, Eddington observed just that effect while watching a total solar eclipse in the South Atlantic. We’re being dynamic here, so the simulation has to include the fact that changes in the mass configuration aren’t felt everywhere instantaneously. Einstein showed that space transmits gravitational waves at the speed of light, so I used a scaled “speed of light” in the calculation. You can see how each of the new features expands outward at a steady rate.

We’re being dynamic here, so the simulation has to include the fact that changes in the mass configuration aren’t felt everywhere instantaneously. Einstein showed that space transmits gravitational waves at the speed of light, so I used a scaled “speed of light” in the calculation. You can see how each of the new features expands outward at a steady rate.