Vinnie lifts his pizza slice and pauses. “I dunno, Sy, this Pressure‑Volume part of enthalpy, how is it energy so you can just add or subtract it from the thermal and chemical kinds?”

“Fair question, Vinnie. It stumped scientists through the end of Napoleon’s day until Sadi Carnot bridged the gap by inventing thermodynamics.”

“Sounds like a big deal from the way you said that.”

“Oh, it was. But first let’s clear the ‘is it energy?’ question. How would Newton have calculated the work you did lifting that slice?”

“How much force I used times the distance it moved.”

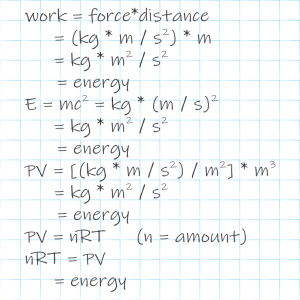

“Putting units to that, it’d be force in newtons times distance in meters. A newton is one kilogram accelerated by one meter per second each second so your force‑distance work there is measured in kilograms times meters‑squared divided by seconds‑squared. With me?”

“Hold on — ‘per second each second’ turned into ‘per second‑squared.” <pause> “Okay, go on.”

“What’s Einstein’s famous equation?”

“Easy, E=mc².”

“Mm-hm. Putting units to that, c is in meters per second, so energy is kilograms times meters‑squared divided by seconds‑squared. Sound familiar?”

“Any time I’ve got that combination I’ve got energy?”

“Mostly. Here’s another example — a piston under pressure. Pressure is force per unit area. The piston’s area is in square meters so the force it feels is newtons per meter‑squared, times square meters, or just newtons. The piston travels some distance so you’ve got newtons times meters.”

“That’s force‑distance work units so it’s energy, too.”

“Right. Now break it down another way. When the piston travels that distance, the piston’s area sweeps through a volume measured in meters‑cubed, right?”

“You’re gonna say pressure times volume gives me the same units as energy?”

“Work it out. Here’s a paper napkin.”

“Dang, I hate equations … Hey, sure enough, it boils down to kilograms times meters‑squared divided by seconds‑squared again!”

“There you go. One more. The Ideal Gas Law is real simple equation —”

“Gaah, equations!”

“Bear with me, it’s just PV=nRT.”

“Is that the same PV so it’s energy again?”

“Sure is. The n measures the amount of some gas, could be in grams or whatever. The R, called the Gas Constant, is there to make the units come out right. T‘s the absolute temperature. Point is, this equation gives us the basis for enthalpy’s chemical+PV+thermal arithmetic.”

“And that’s where this Carnot guy comes in.”

“Carnot and a host of other physicists. Boyle, Gay‑Lussac, Avagadro and others contributed to Clapeyron’s gas law. Carnot’s 1824 book tied the gas narrative to the energetics narrative that Descartes, Leibniz, Newton and such had been working on. Carnot did it with an Einstein‑style thought experiment — an imaginary perfect engine.”

“Anything perfect is imaginary, I know that much. How’s it supposed to work?”

<sketching on another paper napkin> “Here’s the general idea. There’s a sealed cylinder in the middle containing a piston that can move vertically. Above the piston there’s what Carnot called ‘a working body,’ which could be anything that expands and contracts with temperature.”

“Steam, huh?”

“Could be, or alcohol vapor or a big lump of iron, whatever. Carnot’s argument was so general that the composition doesn’t matter. Below the piston there’s a mechanism to transfer power from or to the piston. Then we’ve got a heat source and a heat sink, each of which can be connected to the cylinder or not.”

“Looks straight‑forward.”

“These days, sure. Not in 1824. Carnot’s gadget operates in four phases. In generator mode the working body starts in a contracted state connected to the hot Th source. The body expands, yielding PV energy. In phase 2, the body continues to expand while it while it stays at Th. Phase 3, switch to the cold Tc heat sink. That cools the body so it contracts and absorbs PV energy. Phase 4 compresses the body to heat it back to Th, completing the cycle.”

“How did he keep the phases separate?”

“Only conceptually. In real life Phases 1 and 2 would occur simultaneously. Carnot’s crucial contribution was to treat them separately and yet demonstrate how they’re related. Unfortunately, he died of scarlet fever before Clapeyron and Clausius publicized and completed his work.”

~ Rich Olcott

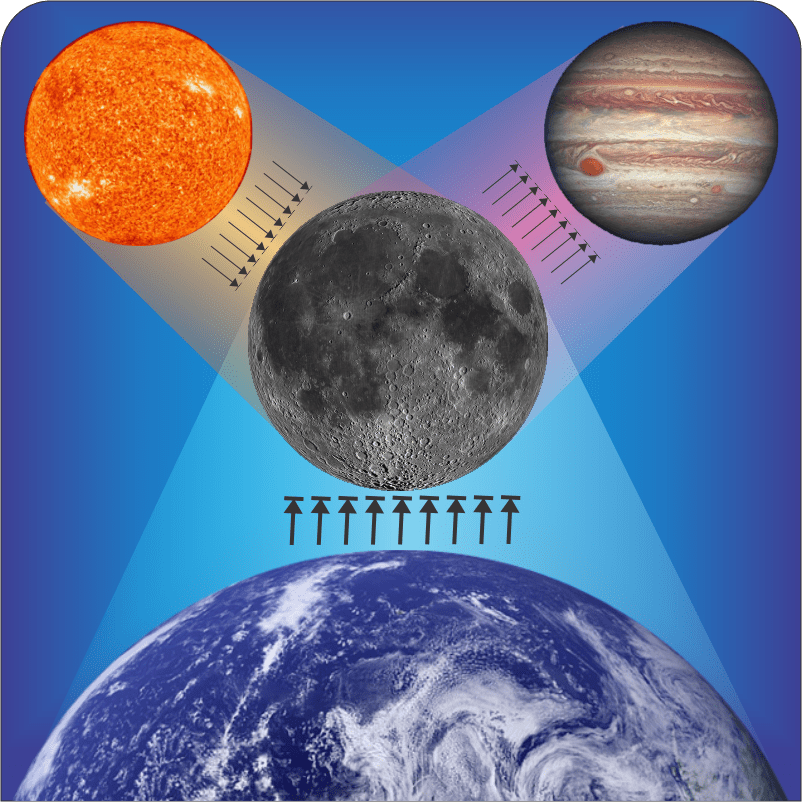

But there are other accelerations that aren’t so easily accounted for. Ever ride in a car going around a curve and find yourself almost flung out of your seat? This little guy wasn’t wearing his seat belt and look what happened. The car accelerated because changing direction is an acceleration due to a lateral force. But the guy followed Newton’s First Law and just kept going in a straight line. Did he accelerate?

But there are other accelerations that aren’t so easily accounted for. Ever ride in a car going around a curve and find yourself almost flung out of your seat? This little guy wasn’t wearing his seat belt and look what happened. The car accelerated because changing direction is an acceleration due to a lateral force. But the guy followed Newton’s First Law and just kept going in a straight line. Did he accelerate? Suppose you’re investigating an object’s motion that appears to arise from a new force you’d like to dub “heterofugal.” If you can find a different frame of reference (one not attached to the object) or otherwise explain the motion without invoking the “new force,” then heterofugalism is a fictitious force.

Suppose you’re investigating an object’s motion that appears to arise from a new force you’d like to dub “heterofugal.” If you can find a different frame of reference (one not attached to the object) or otherwise explain the motion without invoking the “new force,” then heterofugalism is a fictitious force.

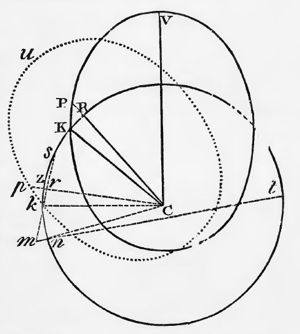

Newton was essentially a geometer. These illustrations (from Book 1 of the Principia) will give you an idea of his style. He’d set himself a problem then solve it by constructing sometimes elaborate diagrams by which he could prove that certain components were equal or in strict proportion.

Newton was essentially a geometer. These illustrations (from Book 1 of the Principia) will give you an idea of his style. He’d set himself a problem then solve it by constructing sometimes elaborate diagrams by which he could prove that certain components were equal or in strict proportion. For instance, in the first diagram (Proposition II, Theorem II), we see an initial glimpse of his technique of successive approximation. He defines a sequence of triangles which as they proliferate get closer and closer to the curve he wants to characterize.

For instance, in the first diagram (Proposition II, Theorem II), we see an initial glimpse of his technique of successive approximation. He defines a sequence of triangles which as they proliferate get closer and closer to the curve he wants to characterize. The third diagram is particularly relevant to the point I’ll finally get to when I get around to it. In Prop XLIV, Theorem XIV he demonstrates something weird. Suppose two objects A and B are orbiting around attractive center C, but B is moving twice as fast as A. If C exerts an additional force on B that is inversely dependent on the cube of the B-C distance, then A‘s orbit will be a perfect circle (yawn) but B‘s will be an ellipse that rotates around C, even though no external force pushes it laterally.

The third diagram is particularly relevant to the point I’ll finally get to when I get around to it. In Prop XLIV, Theorem XIV he demonstrates something weird. Suppose two objects A and B are orbiting around attractive center C, but B is moving twice as fast as A. If C exerts an additional force on B that is inversely dependent on the cube of the B-C distance, then A‘s orbit will be a perfect circle (yawn) but B‘s will be an ellipse that rotates around C, even though no external force pushes it laterally.

It all started with Newton’s mechanics, his study of how objects affect the motion of other objects. His vocabulary list included words like force, momentum, velocity, acceleration, mass, …, all concepts that seem familiar to us but which Newton either originated or fundamentally re-defined. As time went on, other thinkers added more terms like power, energy and action.

It all started with Newton’s mechanics, his study of how objects affect the motion of other objects. His vocabulary list included words like force, momentum, velocity, acceleration, mass, …, all concepts that seem familiar to us but which Newton either originated or fundamentally re-defined. As time went on, other thinkers added more terms like power, energy and action. There is another way to get the same dimension expression but things aren’t not as nice there as they look at first glance. Action is given by the amount of energy expended in a given time interval, times the length of that interval. If you take the product of energy and time the dimensions work out as (ML2/T2)*T = ML2/T, just like Heisenberg’s Area.

There is another way to get the same dimension expression but things aren’t not as nice there as they look at first glance. Action is given by the amount of energy expended in a given time interval, times the length of that interval. If you take the product of energy and time the dimensions work out as (ML2/T2)*T = ML2/T, just like Heisenberg’s Area.