As I stepped off the escalator by the luggage carousel a hand came down heavy on my shoulder.

“Keep movin’, I gotchur bag.”

That’s Vinnie, always the surprises. I didn’t bother to ask how he knew which flight I came in on. What came next was also no surprise.

“You owe me for the pizza. Now about that kinetic energy –”

“Hold that thought ’til we get to my office where I can draw diagrams.”

We got my car out of the lot, drove to the Acme Building and took the elevator to 12.

As my computer booted up I asked, “When we talked about potential energy, did we ever mention inertial frames?”

“Come to think of it, no, we didn’t. How come?”

“Because they’ve got nothing to do with potential energy. Gravitational and electrical potentials are all about intensity at one location in space relative to other locations in space. The potentials are static so long as the configuration is static. If something in the region changes, like maybe a mass moves or the charge on one object increases, then the potential field adjusts to suit.”

“Right, kinetic energy’s got to do with things that move, like its name says. I get that. But how does it play into LIGO?”

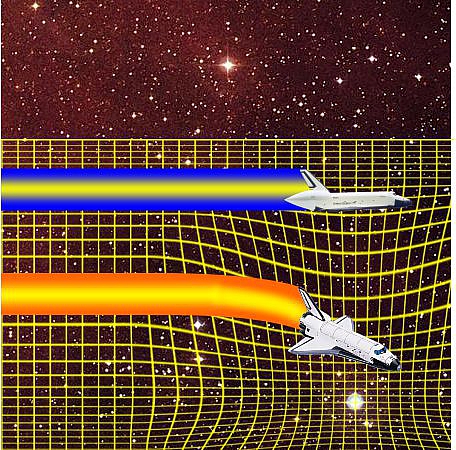

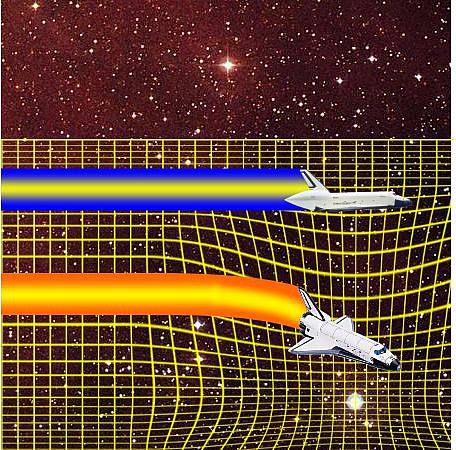

“Let’s stick with our spacecraft example for a bit. I’ve been out of town for a while, so a quick review’s in order. Objects that travel in straight lines and constant speed with respect to each other share the same inertial frame. Masses wrinkle the shape of space. The paths light rays take are always the shortest possible paths, so we say a light ray shows us what a straight line is.

“In our story, we’re flying a pair of space shuttles using identical speed settings along different light-ray navigation beams. Suddenly you encounter a region of space that’s compressed, maybe by a nearby mass or maybe by a passing gravitational wave.

“That compressed space separates our inertial frames. In your inertial frame there’s no effect — you’re still following your nav beam and the miles per second you measure hasn’t changed. However, from my inertial frame you’ve slowed down because the space you’re traveling through is compressed relative to mine. Does all that ring a bell?”

“Pretty much the way I remember it. Now what?”

“Do you remember the formula for kinetic energy?”

“Give me a sec… mass times the square of the velocity.”

“Uh-huh. Mind you, ‘velocity’ is the combination of speed and direction but velocity-squared is just a number. So, your kinetic energy depends in a nice, simple way on speed. What happened to your kinetic energy when you encountered that gravity well?”

“Ah, now I see where you’re going. In my frame my speed doesn’t change so I don’t gain or lose kinetic energy. In your frame you see me slow down so you figure me as losing kinetic energy.”

“But the Conservation of Energy rule holds across the Universe. Where’d your kinetic energy go?”

“Does your frame see me gaining potential energy somehow that I don’t see in mine?”

“Nice try, but that’s not it. We’ve already seen that potential energy doesn’t depend on frames. What made our frames diverge in the first place?”

“That gravity field curving the space I’d flown into. Hey, action-reaction! If the curved space slowed me down, did I speed it up?”

“Now we’re getting there. No, you didn’t speed up space, ’cause space doesn’t work that way — the miles don’t go anywhere. But your kinetic energy (that I can see and you can’t) did act to change the spatial curvature (that I can see and you can’t). I suspect the curvature flattened out, but the math to check that is beyond me.”

“Lemme think… Right, so back to my original question — what I wasn’t getting was how I could lose both kinetic energy AND potential energy flying into that compressed space. Lessee if I got this right. We both see I lost potential energy ’cause I’ve got less than back in flat space. But only you see that my kinetic energy changed the curvature that only you see. Good?”

“Good.”

(sound of footsteps)

(sound of door)

“Don’t mention it.”

~~ Rich Olcott

“That’s what the LaForge Drive does, Mr Moire. The counter-rotating blades are an osmium-

“That’s what the LaForge Drive does, Mr Moire. The counter-rotating blades are an osmium-

“Squeeze in two sides, pop out the other two, eh?”

“Squeeze in two sides, pop out the other two, eh?”

Their common experimental strategy sounds simple enough — compare two beams of light that had traveled along different paths

Their common experimental strategy sounds simple enough — compare two beams of light that had traveled along different paths

Of all the wave varieties we’re familiar with, gravitational waves are most similar to (NOT identical with!!) sound waves. A sound wave consists of cycles of compression and expansion like you see in this graphic. Those dots could be particles in a gas (classic “sound waves”) or in a liquid (sonar) or neighboring atoms in a solid (a xylophone or marimba).

Of all the wave varieties we’re familiar with, gravitational waves are most similar to (NOT identical with!!) sound waves. A sound wave consists of cycles of compression and expansion like you see in this graphic. Those dots could be particles in a gas (classic “sound waves”) or in a liquid (sonar) or neighboring atoms in a solid (a xylophone or marimba). Einstein noticed that implication of his Theory of General Relativity and in 1916 predicted that the path of starlight would be bent when it passed close to a heavy object like the Sun. The graphic shows a wave front passing through a static gravitational structure. Two points on the front each progress at one graph-paper increment per step. But the increments don’t match so the front as a whole changes direction. Sure enough, three years after Einstein’s prediction, Eddington observed just that effect while watching a total solar eclipse in the South Atlantic.

Einstein noticed that implication of his Theory of General Relativity and in 1916 predicted that the path of starlight would be bent when it passed close to a heavy object like the Sun. The graphic shows a wave front passing through a static gravitational structure. Two points on the front each progress at one graph-paper increment per step. But the increments don’t match so the front as a whole changes direction. Sure enough, three years after Einstein’s prediction, Eddington observed just that effect while watching a total solar eclipse in the South Atlantic. We’re being dynamic here, so the simulation has to include the fact that changes in the mass configuration aren’t felt everywhere instantaneously. Einstein showed that space transmits gravitational waves at the speed of light, so I used a scaled “speed of light” in the calculation. You can see how each of the new features expands outward at a steady rate.

We’re being dynamic here, so the simulation has to include the fact that changes in the mass configuration aren’t felt everywhere instantaneously. Einstein showed that space transmits gravitational waves at the speed of light, so I used a scaled “speed of light” in the calculation. You can see how each of the new features expands outward at a steady rate.

We can investigate things that take longer than an instrument’s characteristic time by making repeated measurements, but we can’t use the instrument to resolve successive events that happen more quickly than that. We also can’t resolve events that take place much closer together than the instrument’s characteristic length.

We can investigate things that take longer than an instrument’s characteristic time by making repeated measurements, but we can’t use the instrument to resolve successive events that happen more quickly than that. We also can’t resolve events that take place much closer together than the instrument’s characteristic length.

A wave happens in a system when a driving force and a restoring force take turns overshooting an equilibrium point AND the away-from-equilibrium-ness gets communicated around the system. The system could be a bunch of springs tied together in a squeaky old bedframe, or labor and capital in an economic system, or the network of water molecules forming the ocean surface, or the fibers in the fabric of space (whatever those turn out to be).

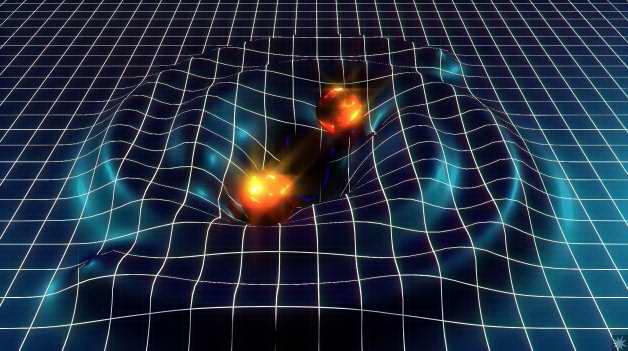

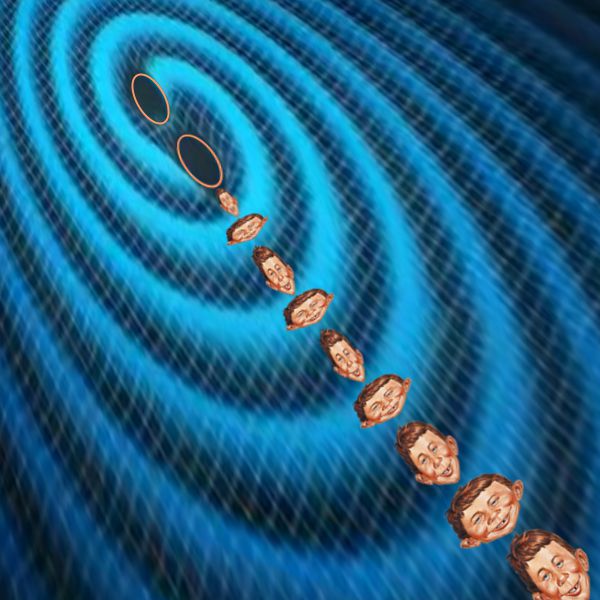

A wave happens in a system when a driving force and a restoring force take turns overshooting an equilibrium point AND the away-from-equilibrium-ness gets communicated around the system. The system could be a bunch of springs tied together in a squeaky old bedframe, or labor and capital in an economic system, or the network of water molecules forming the ocean surface, or the fibers in the fabric of space (whatever those turn out to be). An isolated black hole is surrounded by an intense gravitational field and a corresponding compression of spacetime. A pair of black holes orbiting each other sends out an alternating series of tensions, first high, then extremely high, then high…

An isolated black hole is surrounded by an intense gravitational field and a corresponding compression of spacetime. A pair of black holes orbiting each other sends out an alternating series of tensions, first high, then extremely high, then high…

Almost a century later, James Clerk Maxwell (the bearded fellow at left) wrote down his electromagnetism equations that explain how light works. Half a century later, Einstein did the same for gravity.

Almost a century later, James Clerk Maxwell (the bearded fellow at left) wrote down his electromagnetism equations that explain how light works. Half a century later, Einstein did the same for gravity.

Gravitodynamics is completely unlike electrodynamics. Gravity’s transverse “force” doesn’t act to move a whole mass up and down like Maxwell’s picture at left. Instead, as shown by Einstein’s picture, gravitational waves stretch and compress while leaving the center of mass in place. I put “force” in quotes because what’s being stretched and compressed is space itself. See

Gravitodynamics is completely unlike electrodynamics. Gravity’s transverse “force” doesn’t act to move a whole mass up and down like Maxwell’s picture at left. Instead, as shown by Einstein’s picture, gravitational waves stretch and compress while leaving the center of mass in place. I put “force” in quotes because what’s being stretched and compressed is space itself. See