Mr Feder, of Fort Lee NJ, is outraged. “A pretty pink parasol? NASA spent taxpayer dollars to decorate the James Webb Space Telescope with froufrou like that?”

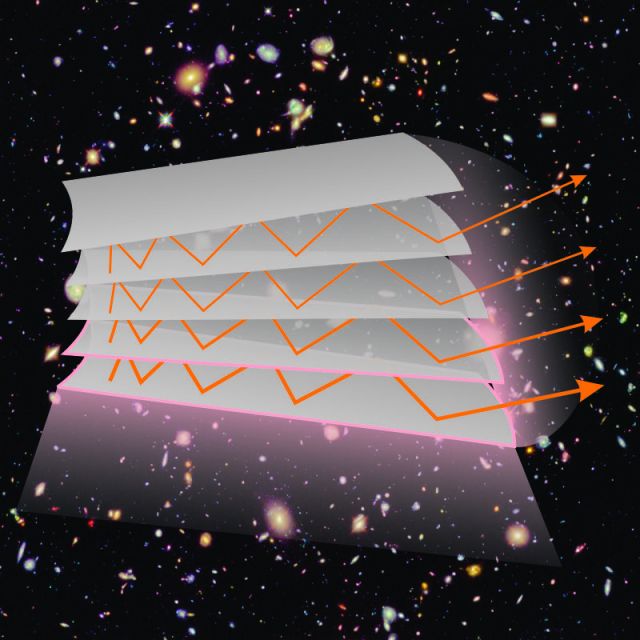

Astronomer Cathleen stays cool. “Certainly not, Mr Feder. This is no effete Victorian‑era parasol. It’s a big, muscular ‘defender against the Sun,’ which is what the word means when you break it down — para‑sol. Long and wide as a tennis court. Its job is to fight off the Sun’s radiation and keep JWST‘s cold side hundreds of degrees colder than the Sun‑facing side. Five layers of high‑strength Kapton film, the same kind that helped protect New Horizons against freezing and micrometeorites on its way to Pluto and beyond. Each layer carries a thin coat of aluminum, looks like a space blanket or those Mylar mirror balloons but this is a different kind of plastic.”

“Sounds like a lot of trouble for insulation. Why not just go with firebrick backed up with cinder blocks? That’s what my cousin used for her pottery kiln.”

I cut in, because Physics. “Two reasons, Mr Feder. First one is mass. Did you help your cousin build her kiln?”

“Nah, bad back, can’t do heavy lifting.”

“There you go. On a space mission, every gram and cubic centimeter costs big bucks. On a benefit/cost scale of 1 to 10, cinder blocks rate at, oh, about ½. But the more important reason is that cinder blocks don’t really address the problem.”

“They keep the heat in that kiln real good.”

“Sure they do, but on JWST‘s hot side the problem is getting rid of heat, not holding onto it. That’s the second reason your blocks fail the suitability test. Sunlight at JWST ‘s orbit will be powerful enough to heat the satellite by hundreds of degrees, your choice of Fahrenheit or centigrade. That’s a lot of heat energy to expel. Convection is a good way to shed heat but there’s no air in space so that’s not an option. Conduction isn’t either, because the only place to conduct the heat to is exactly where we don’t want it — the scope’s dish and instrument packages. Cinder blocks don’t conduct heat as well as metals do, but they do it a lot better than vacuum does.”

“So that leaves what, radiating it away?”

“Exactly.”

“Aluminum on the plastic makes it a good radiator, huh?”

“Sort of. The combo’s a good reflector, which is one kind of radiating.”

“So what’s the problem?”

“It’s not a perfect reflector. The challenge is 250 kilowatts of sunlight. Each layer blocks 99.9% but that still lets 0.1% through to heat up what’s behind it. The parasol has radiate away virtually all the incoming energy. That’s why there’s five layers and they’re not touching so they can’t conduct heat to each other.”

“Wait, they can still radiate to each other. Heat bounces back and forth like between two mirrors, builds up until the whole thing bursts into flames. Dumb design.”

“No flames, despite what the Space Wars movies show, because there’s no oxygen in space to support combustion. Besides, the designers were a lot smarter than that. The mirrors are at an angle to each other, just inches apart near the center, feet apart at the edges. Heat in the form of infrared light does indeed bounce between each pair of layers but it always bounces at an angle aimed outwards. The parasol’s edges will probably shine pretty brightly in the IR, but only from the sides and out of the telescope’s field of view.”

“OK, I can understand the aluminum shiny, but why make it pink?”

“That’s a thin extra coat of a doped silicon preparation, just on the outermost two layers. It’s not so good at reflection but when it heats up it’s good at emitting infrared. Just another way to radiate.”

“But it’s pink?”

“The molecules happen to be that color.”

“Why’s it dopey?”

“Doped, not dopey. Pure silicon is an electrical insulator. Mixing in the right amount of the right other atoms makes the coating a conductor so it can bleed off charge coming in on the solar wind.”

“Geez, they musta thought of everything.”

“They tried hard to.”

~~ Rich Olcott