Cathleen’s got a bit of fire in her eye. “Good exposition, Jeremy, but only just barely on‑assignment. You squeezed in your exoplanet search material at the very end. <sigh> Okay, for our next presentation we have two of our freshmen, Madison and C‑J.”

“Hello, everybody, I’m Madison. I fell in love with Science while watching Nova and Star Trek with my family. Doctor O’Meara’s Astronomy class is my first step into the real thing. C‑J?”

“Hi, I’m C‑J, like she said. What started me on Astronomy was just looking at the night sky. My family’s ranch is officially in dark sky country, but really it’s so not dark. Jeremy’s also from the High Plateau and we got to talking. We see a gazillion stars up there, probably more stars than the Greeks did because they were looking up through humid sea-level air. On a still night our dry air’s so clear you can read by the light of those stars. I want to know what’s up there.”

“Me, too, but I’m even more interested in who‘s up there living on some exoplanet somewhere. How do we find them? We’ve just heard about spectroscopy and astrometry. C‑J and I will be talking about photometry, measuring the total light from something. You can use it even with light sources that are too dim to pick out a spectrum. Photometry is especially useful for finding transits.”

“A transit is basically an eclipse, an exoplanet getting between us and its star—”

“Like the one we had in 2017. It was so awesome when that happened. All the bird and bug noises hushed and the corona showed all around where the Sun was hiding. I was only 12 then but it changed my Universe when they showed us on TV how the Moon is exactly the right size and distance to cover the Sun.”

“Incredible coincidence, right? Almost exactly 100% occultation. If the Moon were much bigger or closer to us we’d never see the corona’s complicated structure. We wouldn’t have that evidence and we’d know so much less about how the Sun works. But even with JWST technology we can’t get near that much detail from other stars.”

“Think of trying to read a blog post on your computer, but your only tool is a light meter that gives you one number for the whole screen. Our nearest star, Alpha Centauri, is 20% larger than our Sun but it’s 4.3 lightyears away. I worked out that at that distance its image would be about 8½ milliarcseconds across. C‑J found that JWST’s cameras can’t resolve details any finer than 8 times that. All we can see of that star or any star is the light the whole system gives off.”

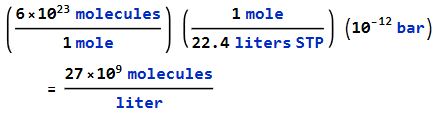

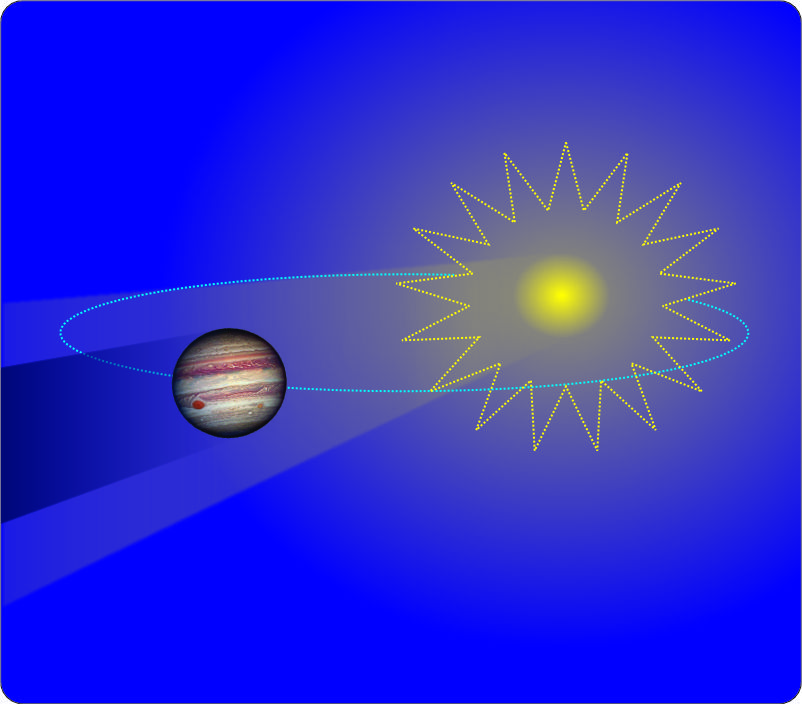

“So here’s where we’re going. We can’t see exoplanets because they’re way too small and too far away, but if an exoplanet transits a star we’re studying, it’ll block some of the light. The question is, how much, and the answer is, not very. Exoplanets block starlight according to their silhouette area. Jupiter’s diameter is about a tenth the Sun’s so it’s area is 1% of the Sun’s. When Jupiter transits the Sun‑‑‑”

“From the viewpoint of some other solar system, of course—”

“Doesn’t matter. Jupiter could get in between the Sun and Saturn; the arithmetic works out the same. The maximum fraction of light Jupiter could block would be its area against the Sun’s area and that’s still 1%.”

“Well, it does matter, because of perspective. If size was the only variable, the Moon is so much smaller than the Sun we’d never see a total eclipse. The star‑planet distance has to be much smaller than the star‑us distance, okay?”

“Alright, but that’s always the way with exoplanets. Even with a big planet and a small star, we don’t expect to measure more than a few percent change. You need really good photometry to even detect that.”

“And really good conditions. Everyone knows how atmospheric turbulence makes star images twinkle—”

“Can’t get 1% accuracy on an image that’s flickering by 50%—”

“And that’s why we had to get stable observatories outside the atmosphere before we could find exoplanets photometrically.”

~~ Rich Olcott