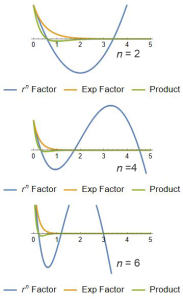

“Whoa, Sy, something’s not right. Your zonal harmonics — I can see how latitudes go from pole to pole and that’s all there are. Your sectorial harmonic longitudes start over when they get to 360°, fine. But this chart you showed us says that the radius basically disappears crazy close to zero. The radius should keep going forever, just like x, y and z do.”

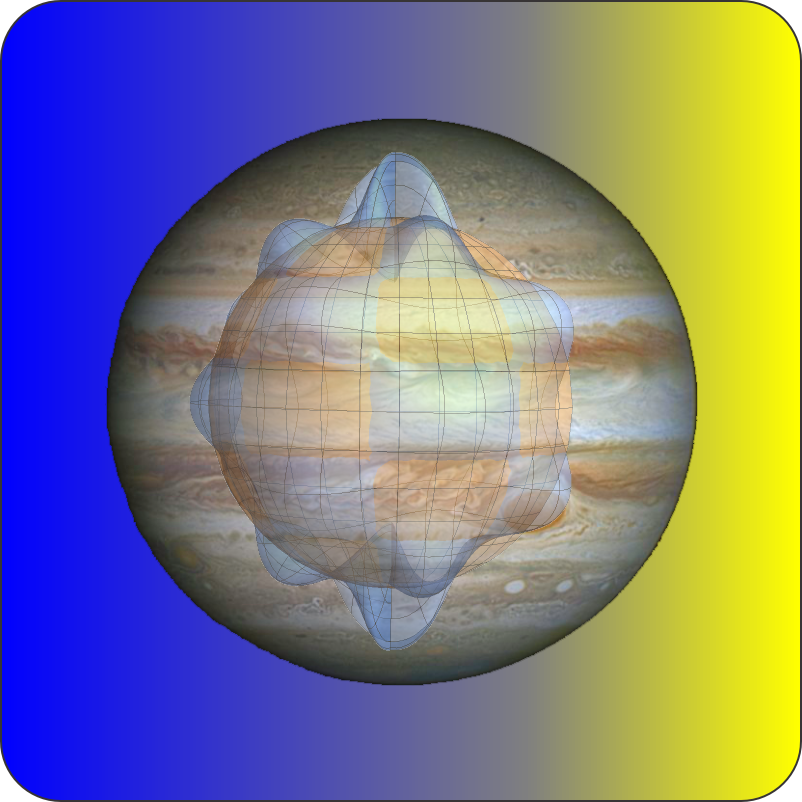

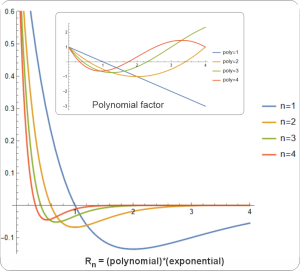

“Ah, I see the confusion, Susan. The coordinate system and the harmonic systems and the waves are three different things, um, groups of things. You can think of a coordinate system as a multilevel stage where chords of harmonic musicians can interact to play a composition of wave signals. The spherical system has latitude and longitude levels for the brass and woodwind players, plus one in back for the linear percussion section. Whichever direction the brass and woodwinds point, that’s where the signals go out, but it’s the percussion that determines how far they get. Sure, radius lines extend to infinity but except for R0 radial harmonics damp out pretty quickly.”

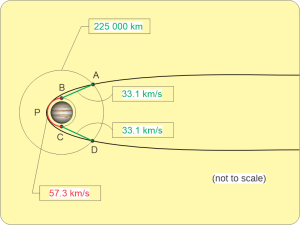

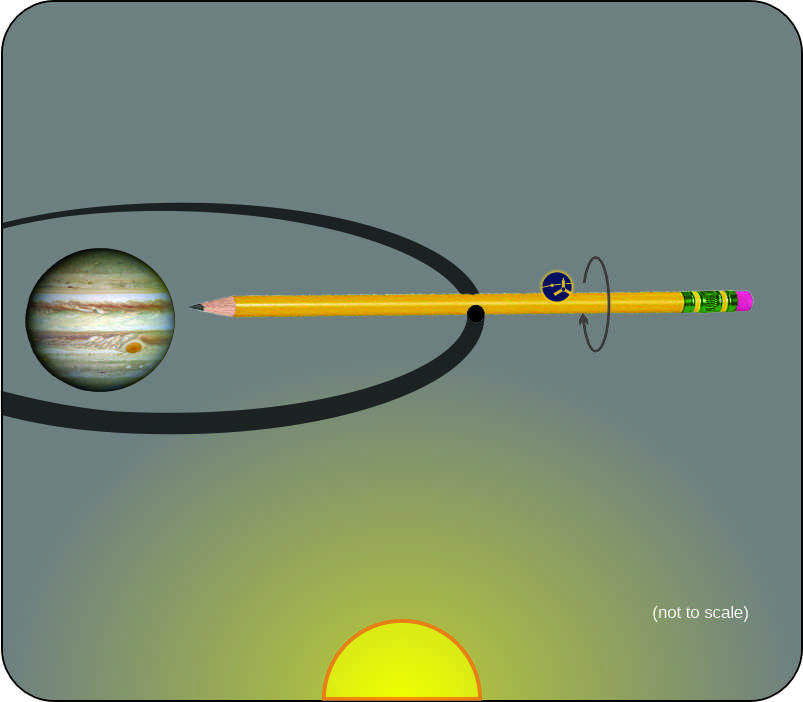

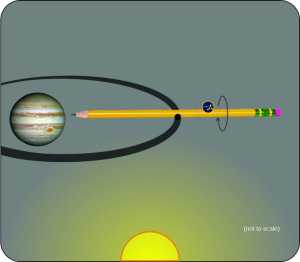

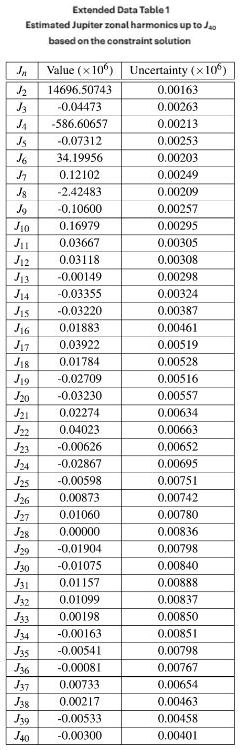

“Signals… Like Kaski’s team interpreted Juno‘s orbital twitches as a signal about Jupiter’s gravitational unevenness. Good thing Juno got close enough to be inside the active range for those radial harmonics. How’d they figure that?”

“They probably didn’t, Cathleen, because radial harmonics don’t fit easily into real situations. First problem is scale — what units do you measure r in? There’s an easy answer if the system you’re working with is a solid ball, not so easy if it’s blurry like a protein blob or galaxy cluster.”

“What makes a ball easy?”

“Its rigid surface that doesn’t move so it’s always a node. Useful radial harmonics must have a node there, another node at zero and an integer number of nodes between. Better yet, with the ball’s radius as a natural length unit the r coordinate runs linearly between zero at the center and 1.0 at the surface. Simplifies computation and analysis. In contrast, blurries usually don’t have convenient natural radial units so we scrabble around for derived metrics like optical depth or mixing length. If we’re forced into doing that, though, we probably have worse challenges.”

“Like what?”

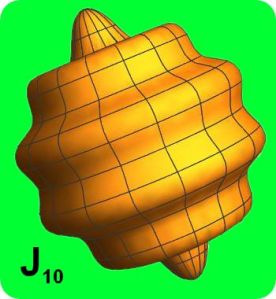

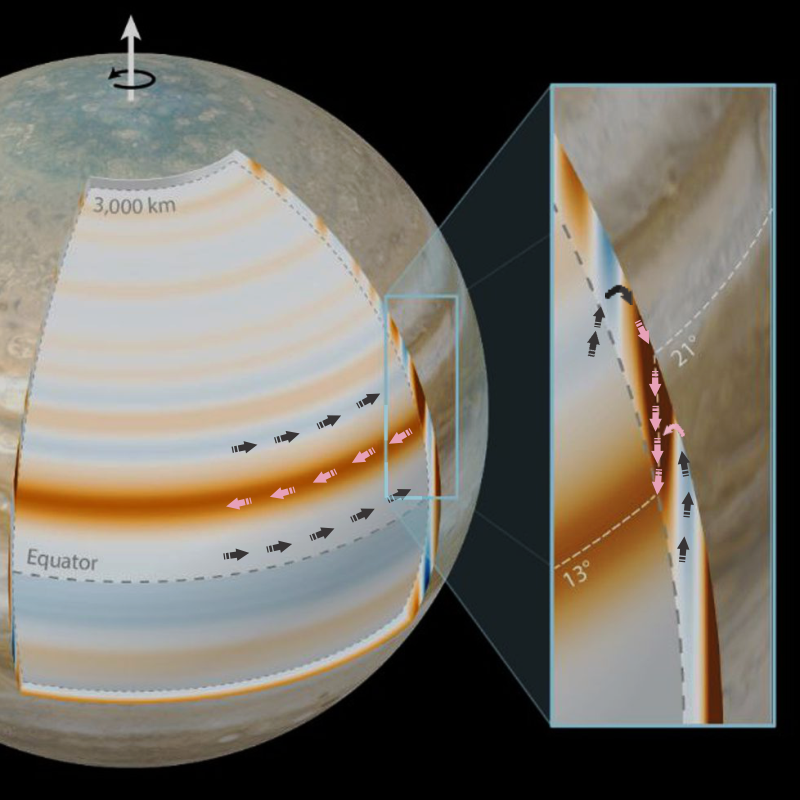

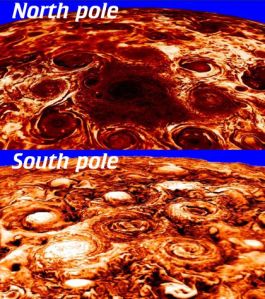

“Most real-world spherical systems aren’t the same all the way through. Jupiter, for instance, has separate layers of stratosphere, troposphere, several chemically distinct cloud‑phases, down to helium raining on layers of hydrogen in liquid, maybe slushy or even solid form. Each layer has its own suite of physical properties that put kinks into a radial harmonic’s smooth curve. Same problem with the Sun.”

“How about my atoms? The whole Periodic Table is based on atoms having a shell structure. What about the energy level diagrams for atomic spectra? They show shells.”

“Well, they do and they don’t, Susan. Around the turn of the last Century, Lyman, Balmer, Paschen, Brackett and Pfund—”

“Sounds like a law firm.”

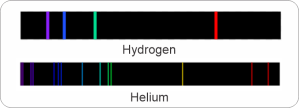

“<ironically> Ha, ha. No, they were experimental physicists who gave the theoreticians an important puzzle. Over a 40‑year period first Balmer and then the others, one series at a time, measured the wavelengths of dozens of lines in hydrogen’s spectrum. ’Okay, smarties, explain those!‘ So the theoreticians invented quantum mechanics. The first shot did a pretty good job for hydrogen. It explained the lines as transitions between discrete states with different energy levels. It then explained the energy levels in terms of charge being concentrated at different distances from the nucleus. That’s where the shell idea came from. Unfortunately, the theory ran into problems for atoms with more than one electron.”

“Give us a second… Ah, I get why. If one electron avoids a node, another one dives in there and that radius isn’t a node any more.”

“Got it in one, Cathleen. Although I prefer to think of electrons as charge clouds rather than particles. Anyhow, when an atom has multiple charge concentrations their behavior is correlated. That opens the door to a flood of transitions between states that simply aren’t options for a single‑electron system. That’s why the visible spectrum of helium, with just one additional electron, has three times more lines than hydrogen does.”

“So do we walk away from spherical harmonics for atoms?”

“Oh, no, Susan, your familiar latitude and longitude harmonics fit well into the quantum framework. These days, though, we mostly use combinations of radial fade‑aways like my Sn00 example.”

~~ Rich Olcott