“Was it just my imagination, Kareem, or was there some side action going on in that Africa‑Eurasia nutcracker video?”

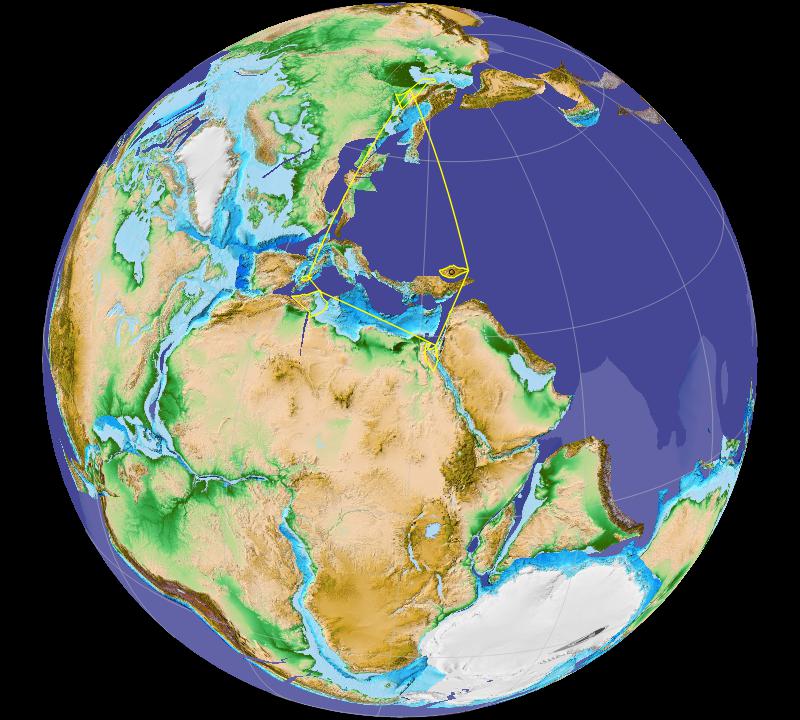

“Always the trained observer, eh, Sy? You’re right, India had an interesting life in the same era. Here, let me bring up another Gplates video on Old Reliable. I need to show both sides of the world so I’ll switch from orthographic to Mollweide projection. Aannd I don’t need to go quite as far back, only to about 120 million years. Mmm, yeah, I’ll squeeze in some special markings, give me a sec… There. This slick enough for you?”

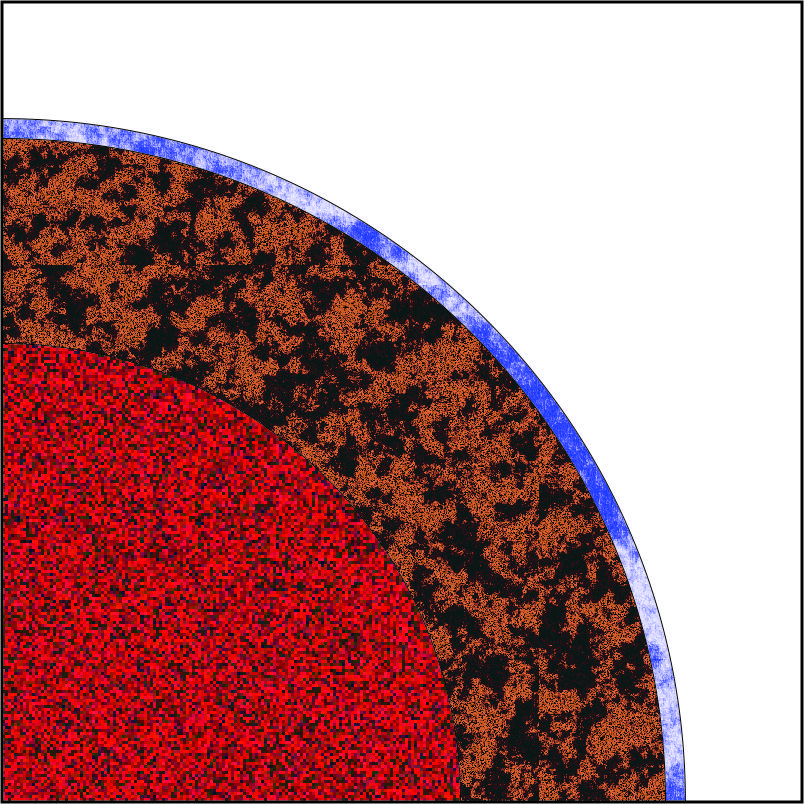

rendered using the GPlates system

and configuration data from Müller, et al., 2019, doi.org/10.1029/2018TC005462

“Busy, indeed. Care to read out what‑all is happening?”

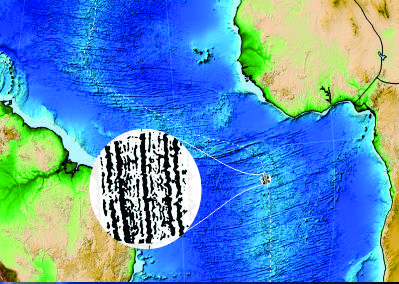

“Sure. The big thing, of course, is the new ocean opening up around the Mid-Atlantic Rift. Further south, by 120 million years ago Gondwanaland had already calved off South America and Africa so all it had left was Madagascar, India, Australia and the Antarctic.”

“Somehow I’d always thought that Madagascar was tied to southern Africa, but I guess not.”

“Hasn’t been for 175 million years, and back then it was up level with where Kenya and Somalia are now. OK, what caught your eye east of Africa was India zoomin’ on up there three times faster than South America was drifting away from Africa. What I’ve done here, I locked the display onto Antarctica so everything’s moving relative to that even though Antarctica wandered around a bit, too. Then I marked a spot in central India, dialed back to 120 million years ago and started scanning forward by three‑million-year increments. At each step I put an orange dot over my marked spot. The dot sequence shows the subcontinent’s motion up to today. You can see it’s not a straight line and the points aren’t evenly spaced.”

“The uneven spacing and wiggly line say that India didn’t move at constant velocity.”

“Spoken like a true physicist.”

“And like any physicist who sees a velocity change I wonder about the forces that make that happen. That red dot, for instance, why did it break the pattern?”

“The red dot is special because it marks 66 million years ago. Does that date ring a bell with you?”

“Umm … Ah-hah! That was the meteor that killed off the dinosaurs, right?”

“The Chicxulub impactor had a lot to do with it, but that wasn’t the whole story. The dot is already far ahead of where it should have been considering India’s previous vector. Something happened that sped that plate along a good three million years before the meteor hit. We’re pretty sure the something was related to massive continental volcanic activity on India just south of where my dots are. The lava covered half the continent, six hundred thousand square miles. All that molten discharge undoubtedly came along with toxic gases that would have fouled the planet’s atmosphere and troubled the dinosaurs and everything else trying to breathe,”

“And what caused the volcanoes?”

“Really bad luck. There’s an active hotspot, we call it Réunion after the French island that’s on top of it at the moment. India just happened to pass right over the hotspot between 69 and 63 million years ago. The spot’s rising magma punched through the subcontinent’s bedrock, ran all over the place and maybe lubricated the passage. Then along comes the meteor when India’s only halfway across the hotspot. The asteroid doesn’t hit India but where it hits is almost as bad — just off the Mexican coast, almost exactly on the other side of the planet from where India is at the time. Imagine a massive ring of violent earthquakes sweeping around the Earth’s surface and coming to a focus smack in the middle of the volcanoes. That’s my shooting red line, except the shakers really come at India from every direction. The magma outflow rate doubles. Altogether, the discharge finally lays over 1015 metric tons of lava on top of poor India and whatever’s living there at the time.”

“Wow. Talk about your perfect storm.”

“The only good thing to come out of it is all the minerals in the magma left India with incredibly fertile soil.”

“That’s something.”

~~ Rich Olcott