<creak> Teena’s enjoying her new-found power in the swings. “Hey, Uncle Sy? <creak> Why doesn’t the Earth fall into the Sun?”

“What in the world got you thinking about that on such a lovely day?”

“The Sun gets in my eyes when I swing forward <creak> and that reminded me of the time we saw the eclipse <creak> and that reminded of how the planets and moons are all floating in space <creak> and the Sun’s gravity’s holding them together but if <creak> the Sun’s pulling on us why don’t we just fall in?” <creak>

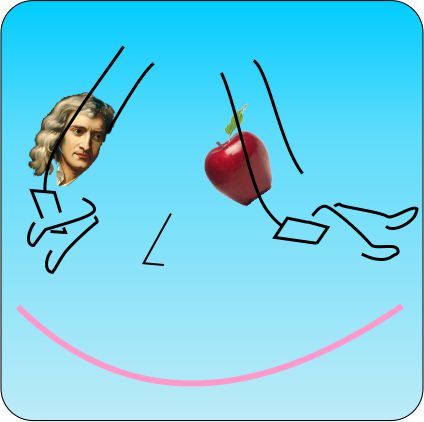

“An excellent question, young lady. Isaac Newton thought about it long and hard back when he was inventing Physics.”

“Isaac Newton? Is he the one with all the hair and a long, skinny nose and William Tell shot an arrow off his head?”

“Well, you’ve described his picture, but you’ve mixed up two different stories. William Tell’s apple story was hundreds of years before Newton. Isaac’s apple story had the fruit falling onto his head, not being shot off of it. That apple got him thinking about gravity and how Earth’s gravity pulling on the apple was like the Sun’s gravity pulling on the planets. When he was done explaining planet orbits, he’d also explained how your swing works.”

“My swing works like a planet? No, my swing goes back and forth, but planets go round and round.”

“Jump down and we can draw pictures over there in the sandbox.”

<thump!! scamper!> “I beat you here!”

“Of course you did. OK, what’s your new M-word?”

“Mmmo-MMENN-tummm!”

“Right. Mr Newton’s Law of Inertia is about momentum. It says that things go in a straight line unless something interferes. It’s momentum that keeps your swing going.”

“B-u-u-t, I wasn’t going in a straight line, I was going in part of a circle.”

“Good observing, Teena, that’s exactly right. Mr Newton’s trick was that a really small piece of a circle looks like a straight line. Look here. I’ll draw a circle … and inside it I’ll put a triangle… and between them I’ll put a hexagon — see how it has an extra point halfway between each of the triangle’s points? — and up top I’ll put the top part of whatever has 12 sides. See how the 12-thing’s sides are almost on the circle?”

“Ooo, that’s pretty! Can we do that with a square, too?”

“Sure. Here’s the circle … and the square … and an octagon … and a 16-thing. See, that’s even closer to being a circle.”

“Ha-ha — ‘octagon’ — that’s like ‘octopus’.”

“For good reason. An octopus has eight arms and an octagon has eight sides. ‘Octo-‘ means ‘eight.’ So anyway, Mr Newton realized that his momentum law would apply to something moving along that tiny straight line on a circle. But then he had another idea — you can move in two directions at once so you can have momentum in two directions at once.”

“That’s silly, Uncle Sy. There’s only one of me so I can’t move in two directions at once.”

“Can you move North?”

“Uh-huh.”

“Can you move East?”

“Sure.”

“Can you move Northeast?”

“Oh … does that count as two?”

“It can for some situations, like planets in orbit or you swinging on a swing. You move side-to-side and up-and-down at the same time, right?”

“Uh-huh.”

“When you’re at either end of the trip and as far up as you can get, you stop for that little moment and you have no momentum. When you’re at the bottom, you’ve got a lot of side-to-side momentum across the ground. Anywhere in between, you’ve got up-down momentum and side-to-side momentum. One kind turns into the other and back again.”

“So complicated.”

“Well, it is. Newton simplified things with revised directions — one’s in-or-out from the center, the other’s the going-around angle. Each has its own momentum. The swing’s ropes don’t change length so your in-out momentum is always zero. Your angle-momentum is what keeps you going past your swing’s bottom point. Planets don’t have much in-out momentum, either — they stay about their favorite distance from the Sun.”

“Earth’s angle-momentum is why we don’t fall in?”

“Yep, we’ve got so much that we’re always falling past the Sun.”

~~ Rich Olcott

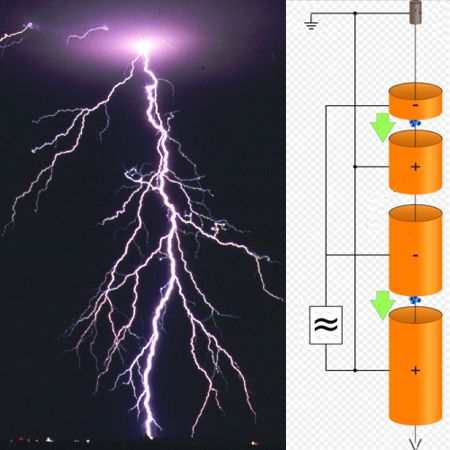

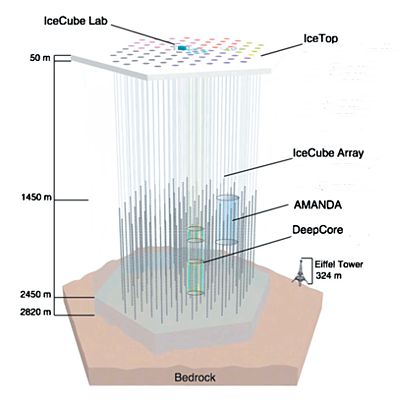

“Why should there be flashes? I thought neutrinos didn’t interact with matter.”

“Why should there be flashes? I thought neutrinos didn’t interact with matter.”

“Hello, Jennie. Haven’t seen you for a while.”

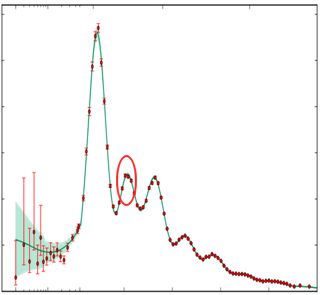

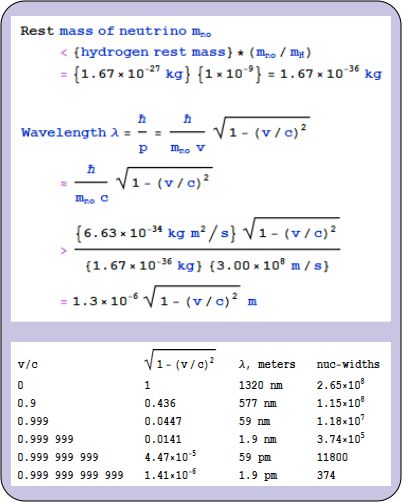

“Hello, Jennie. Haven’t seen you for a while.” Momentum is velocity times mass. These guys fly so close to lightspeed that for a long time scientists thought that neutrinos are massless like photons. They’re not, so I used several different v/c ratios to see what the relativistic correction does. Slow neutrinos are huge, by atom standards. Even the fastest ones are hundreds of times wider than a nucleus.”

Momentum is velocity times mass. These guys fly so close to lightspeed that for a long time scientists thought that neutrinos are massless like photons. They’re not, so I used several different v/c ratios to see what the relativistic correction does. Slow neutrinos are huge, by atom standards. Even the fastest ones are hundreds of times wider than a nucleus.”