“You guys want refills? You look like you’re gonna be here a while.”

“Yes, thanks, Al. Your lattes are sooo good. And can we have some more paper napkins?”

“Sure, but don’t let ’em blow away or nothin’, OK? I hate havin’ to pick up the place.”

“They’ll stay put. Just a half-cup of mud for me, thanks.”

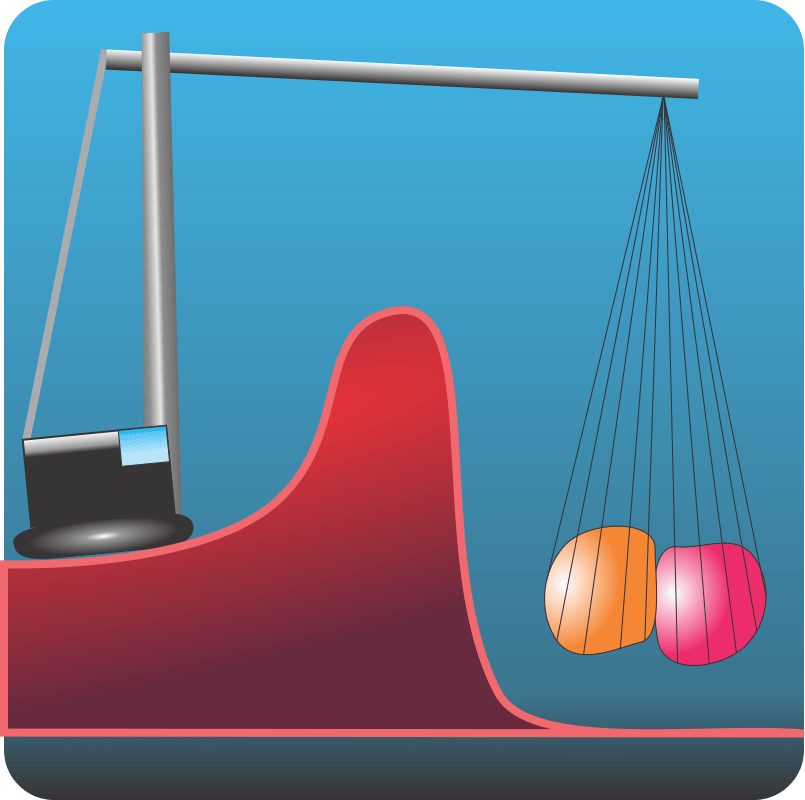

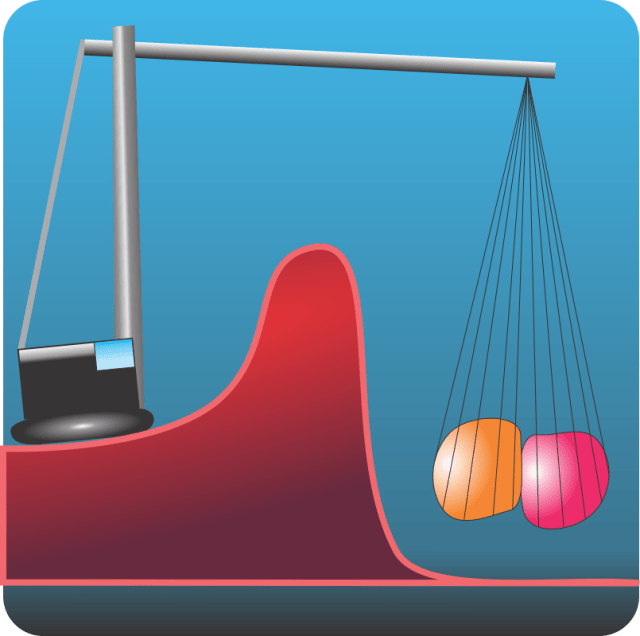

The Spring breeze has picked up a little so we hitch our chairs closer together. Susan reaches for a paper napkin, draws a curve. “Here’s another pattern you haven’t featured yet, Sy. It’s in every chemist’s mind when they think about reactions.”

“OK, I suppose this is molecules A and B on one side of some sort of wall and molecule C on the other.”

“It’ll be clearer if I label the axes. It’s a reaction between A and B to make C. The horizontal axis isn’t a distance, it’s a measure of the reaction’s progress toward completion. Beginning molecules to the left, completed reaction to the right, transition in the middle, see? The vertical axis is energy. We say the reaction is energetically favored because C is lower than A and B separately.”

“Then what’s the wall?”

“We call it the barrier. It’s some additional dollop of energy that allows the reaction happen. Maybe A or B have to be reconfigured before they can form an A~B transition state. That’s common in carbon chemistry, for instance. Carbon usually has four bonds, but you can get five‑bonded transition states. They usually don’t last very long, though.”

“Right, carbon and its neighbors prefer the tetrahedral shape. Five‑bonded carbon distorts the stable electron clouds. Heat energy shoves things into position, I suppose.”

“Often but hardly always. Especially for large molecules, heat’s more likely to jostle things out of position than put them together. That’s what cooking does.”

“The curve reminds me of particle accelerator physics, except it takes way more energy to overcome nuclear forces when you mash sub‑atomic thingies together.”

“Oh, yes, very similar in terms of that general picture — except that the C side could be multiple emitted particles.”

“So your sketch covers a processes everywhere, not just Chemistry. They all have different barrier profiles, then?”

“Of course. My drawing was just to give you the idea. Some barriers are high, some are low, either side may rise or fall exponentially or by some power of the distance, some are lumpy, it all depends. Some are even flat.”

“Flat, like no resistance at all?”

“Oh, yes. Hypergolic rocket fuel pairs ignite spontaneously when they mix. Water and alkali metals make flames — have you seen that video of metallic sodium dumped into a lake and exploding like mad? Awesome!”

“I can imagine, or maybe not. If heat energy doesn’t get molecules over that barrier, what does?”

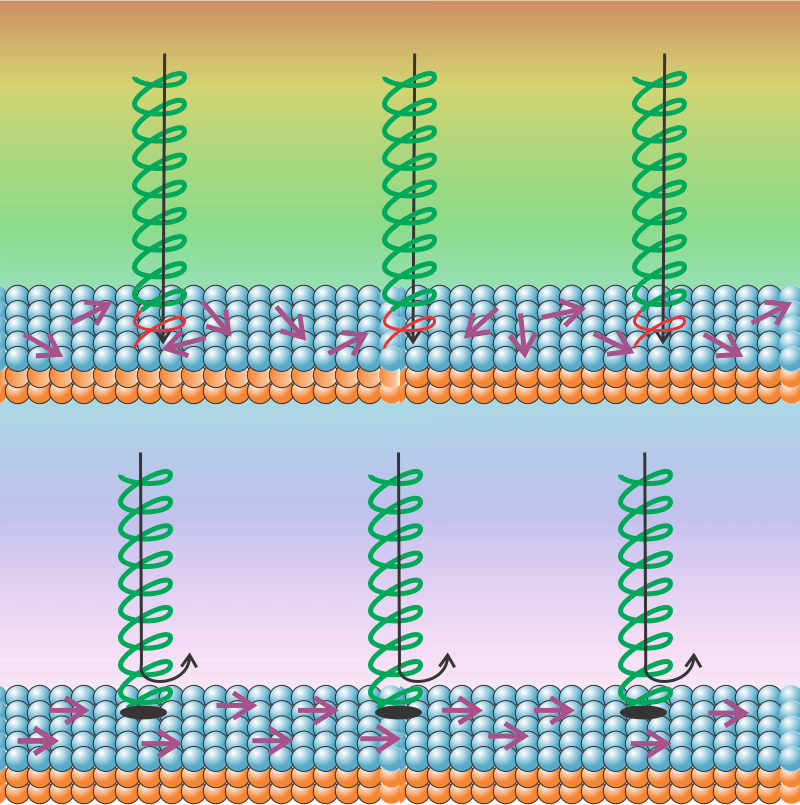

“Catalysts, mostly. Some do their thing by capturing the reactants in adjacent sites, maybe doing a little geometry jiggling while they’re at it. Some play games with the electron states of one or both reactants. Anyhow, what they accomplish is speeding up a reaction by replacing the original barrier with one or more lower ones.”

“Wait, reaction speed depends on the barrier height? I’d expect either go or no‑go.”

“No, it’s usually more complicated than that. Umm … visualize tossing a Slinky toy into the air. Your toss gives it energy. Part of the energy goes into lifting it against Earth’s gravity, part into spinning motion and part into crazy wiggles and jangling, right? But if you toss just right, maybe half of the energy goes into just stretching it out. Now suppose there’s a weak spot somewhere along the spring. Most of your tosses won’t mess with the spot, but a pure stretch toss might have enough energy to break it apart.”

“Gotcha, the transition barrier might be a probability thing depending on how the energy’s distributed within A and B. Betcha tunneling can play a part, too.”

“Mm? Oh, of course, you’re a Physics guy so you know quantum. Yes, some reactions depend upon electrons or hydrogen atoms tunneling through a barrier, but hardly ever anything larger than that. Whoops, I’m due back at the lab. See ya.”

<inaudible> “Oh, I hope so.”

~~ Rich Olcott