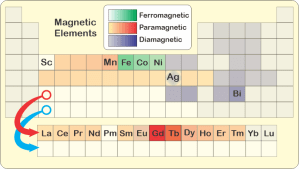

The game‘s over but there’s still pizza on the table so Eddie picks up the conversation. “So if gadolinoleum has even more unpaired electrons than iron, how come it’s not ferromagnetic like iron is?”

Vinnie’s tidying up the chips he just won. “I bet I know part of it, Eddie. Sy and me, we talked about magnetic domains some years ago. If I remember right, each iron atom in a chunk is a tiny little magnet, which I guess is the fault of its five unpaired electrons, but usually the atom magnets are pointing in all different directions so they all average out and the whole chunk doesn’t have a field. If you stroke the chunk with a magnet, that collects the little magnets into domains and the whole thing gets magnetic. How come gadomonium” <winks at Eddie, Eddie winks back> “doesn’t play the domain game, Susan?”

“It’s gadolinium, boys, please. As to the why, part’s at the atom level and part’s higher up. My lab neighbor Tammy schooled me on rare earth magnetism just last week. She does high‑temperature solid state chemistry with lanthanide‑containing materials. Anyway, she says it’s all about coupling.”

“I hope she told you more than that.”

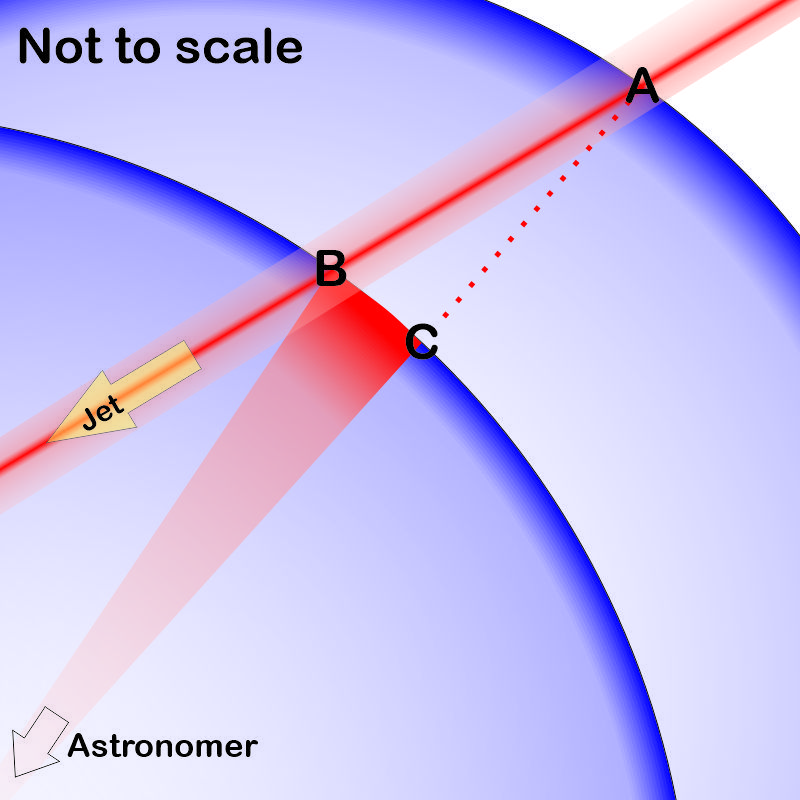

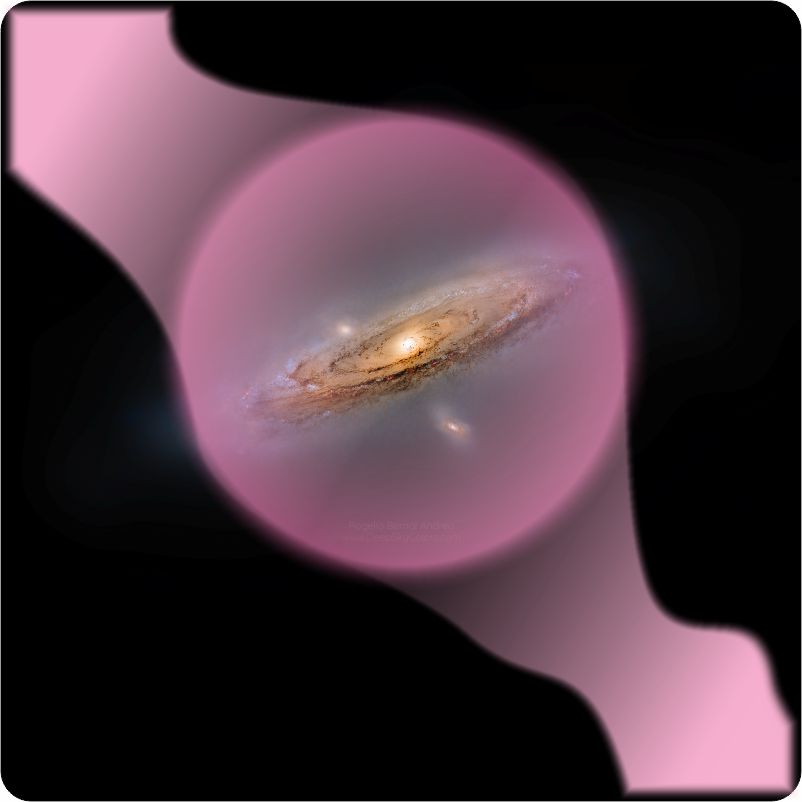

Credit: Inigo.quilez, under CCA SA 3.0 license

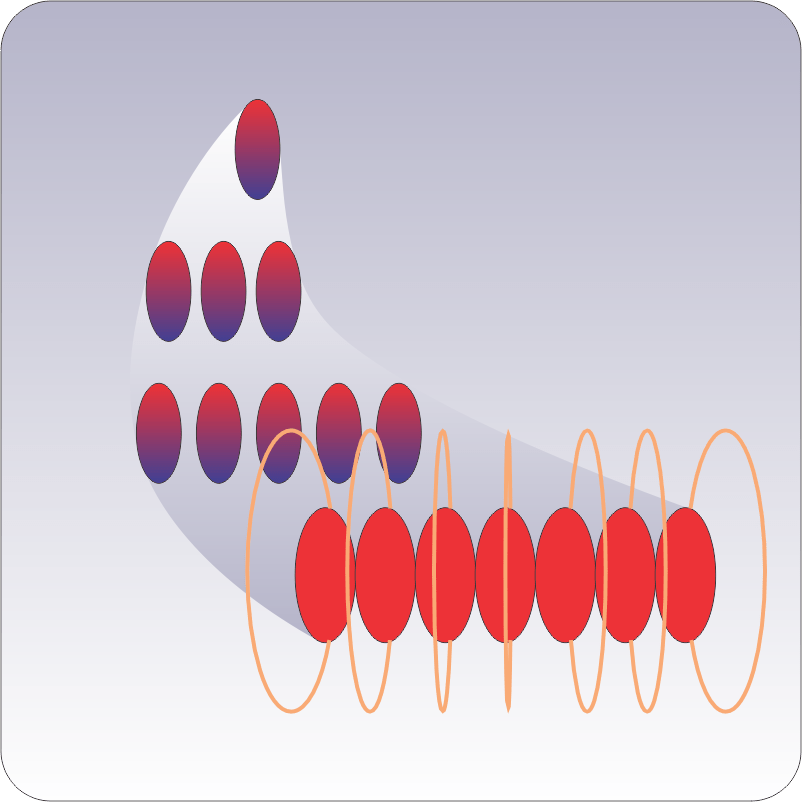

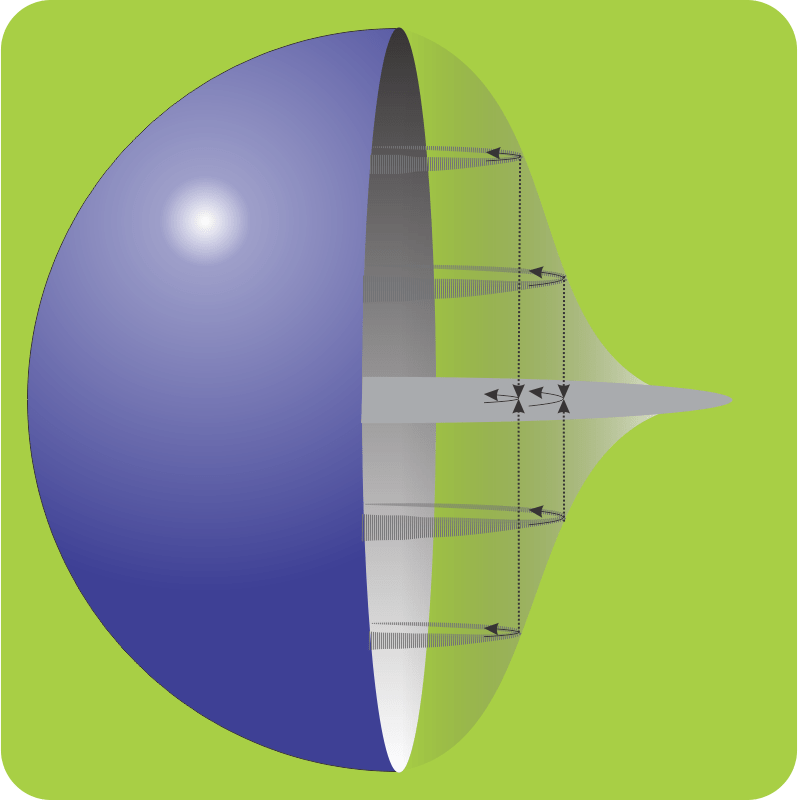

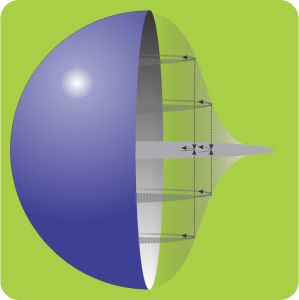

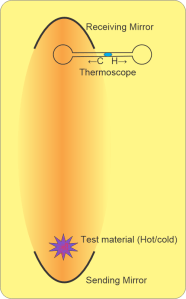

“She did. Say you’ve got a single gadolinium atom floating in space. Its environment is spherically symmetrical, no special direction to organize the wave‑orbitals hosting unpaired charges. Now turn on a magnetic field to tell the atom which way is up, call that the z‑axis. The atom’s wave‑orbital with zero angular momentum orients along z. Six more wave‑orbitals with non‑zero angular momentum spin one way or the other at various angles to the z‑axis. Those charges in motion build the atom’s personal magnetic field.”

“But we’re on Earth, not in space.”

“Bear with me. First, as a chemist I must say that most of the transition and lanthanide elements happily lose two electrons so in general we’re dealing with ions. Before you ask, Vinnie, that goes even for metals where the ions float in an electron sea. When Tammy said ‘coupling’ she was talking about how strongly one ion feels the neighboring fields. Iron and other ferromagnetic materials have a strong coupling, much stronger than the paramagnetics do.”

“Why’s the ferro- coupling so much stronger?”

“Two effects. You can read both of them right off the Periodic Table. Physical size, for one. Each row down in the table represents one electronic shell which takes up space. The atom or ion in any row is bigger than the ones above it. Yes, the heavy elements have more nuclear charge to pull electronic charge close, but shielding from their completed lower shells lets the outer charge cloud expand. Tammy told me that gadolinium’s ions are about 20% wider than iron’s.”

“Makes sense — you make the ions get further apart, they won’t connect so good. What’s the other effect?”

“It’s about how each orbital distributes its charge. There are tradeoffs between shell number, angular momentum and distance from the nucleus. Unpaired charge concentration in gadolinium’s high‑momentum 4f‑orbitals on the average stays inside of all its 3‑shell waves. The outermost charge shelters the unpaired waves inside it. That weakens magnetic coupling with unpaired charge in neighboring ions. Bottom line — gadolinium and its cousins are paramagnetic because they’re bigger and less sensitive than ferromagnetic iron is.”

“Then how come rare earth supermagnets the Chinese make are better than the cheapie ironic kinds we can make here?”

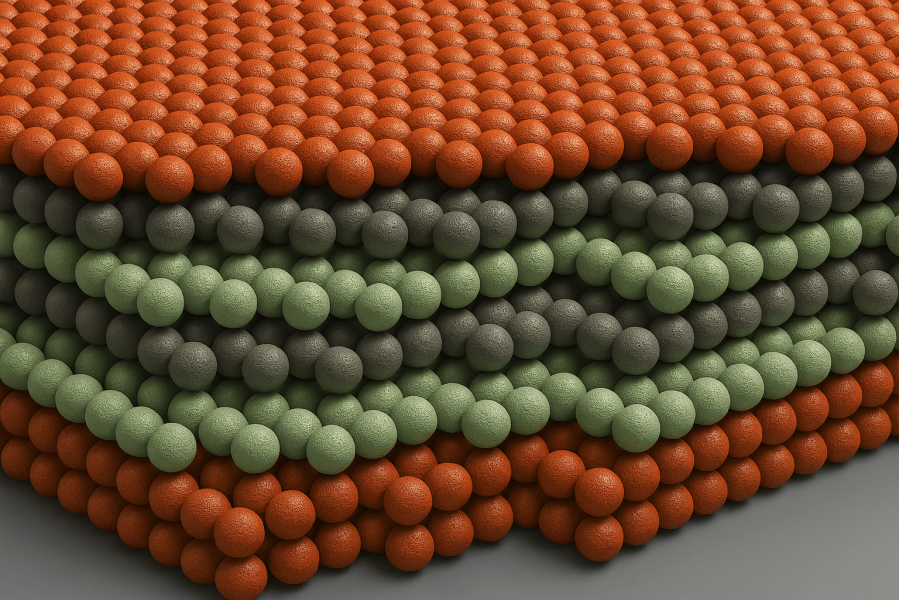

“The key is getting the right atoms into the right places in a crystalline solid. Neodymium magnets, for instance, have clusters of iron atoms around each lanthanide. The cluster arrangement aligns everyone’s z‑axes letting the unpaired charges gang up big‑time. You find materials like that mostly by luck and persistence. Tammy’s best samples are multi‑element oxides that arrange themselves in planar layers. Pick a component just 1% off the ideal size or cook your mixture with the wrong temperature sequence and the structure has completely different properties. Chinese scientists worked decades to perfect their recipes. USA chose to starve research in that area.”

~ Rich Olcott