Vinnie plops down by our table at Cal’s Coffee. “Hi, guys. Glad you’re both here. Susan, Sy here says you’re an RDX expert so I got a question.”

“Not an expert, Vinnie, it’s just one of a series of compounds in one of my projects. What’s your question?”

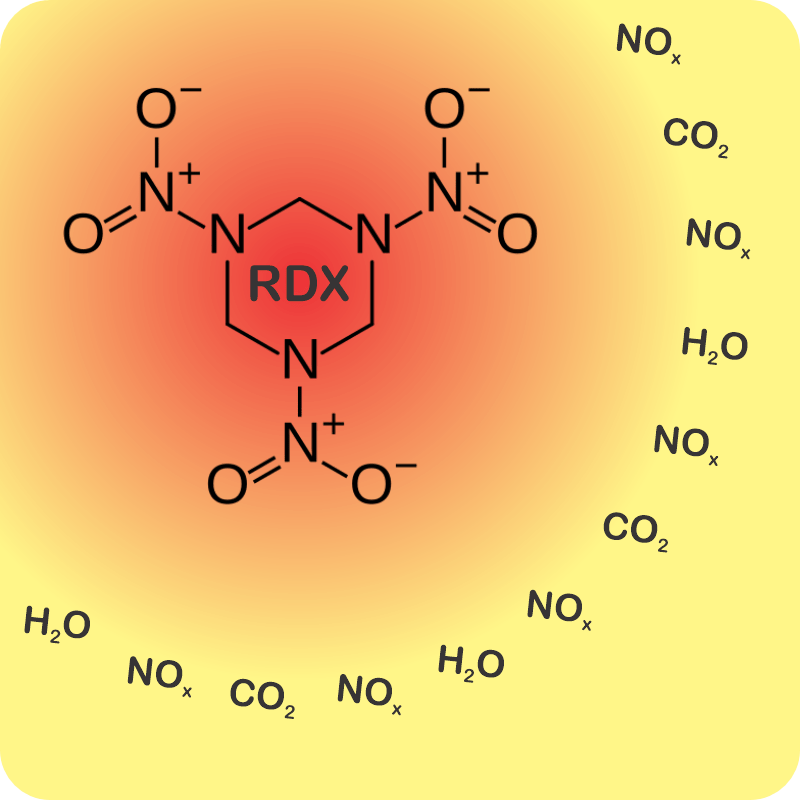

“How come the stuff is so touchy but it’s not touchy? You can shoot a bullet into a lump of it, nothing happens, but set off a detonator next to it and WHAMO! Why do we need a detonator, and what’s in one anyway?”

“Sy, what sets off an H‑bomb?”

“An A‑bomb. You need a lot of energy in a confined region to crowd those protons enough that they fuse.”

“And what sets off an A‑bomb?”

“Hey I know that one, Susan, I saw the Oppenheimer movie. You need some kind of explosives going off just right to cram two chunks of plutonium together real fast so they do the BANG! thing instead of just melting. Wait! I see where you’re going — little explosions trigger big explosions, right?”

“Bravo! You’ve got the idea behind activation energy.”

“Geez, another kind of energy?”

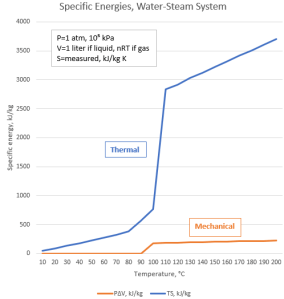

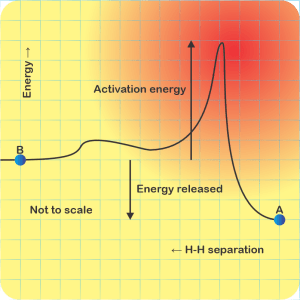

“Yes and no, Vinnie. Enthalpy and its cousins are about the net change when something happens. We can use them to predict how a complex reaction will settle down, but they don’t tell us much about the kinetics, how fast things will happen. Think for a minute about those H‑bomb hydrogen atoms. What prevents them from fusing?”

“I guess under normal conditions they’re too far apart and even when they get close their electron clouds push against each other.”

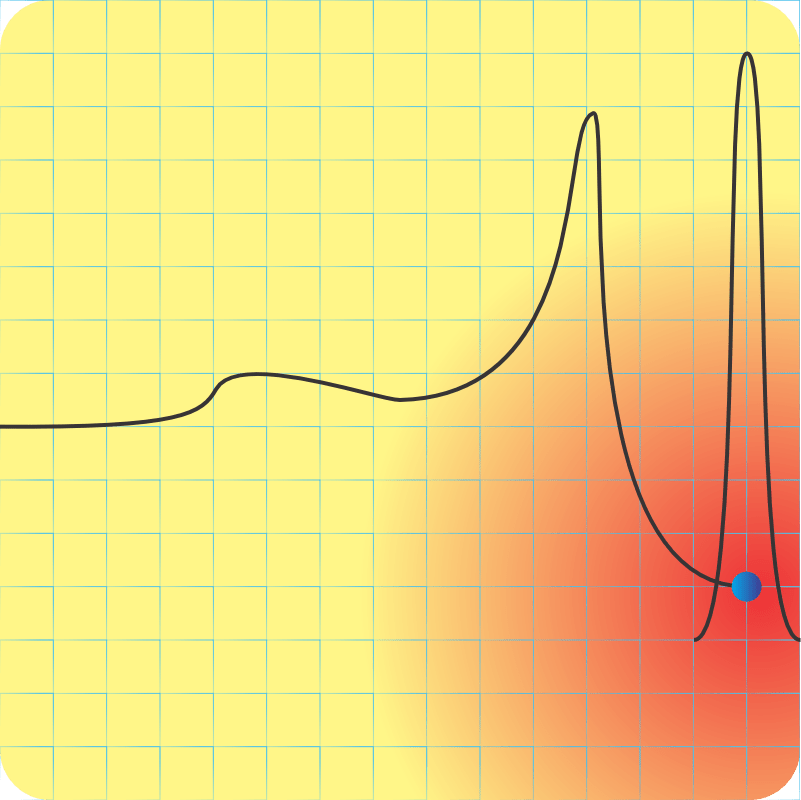

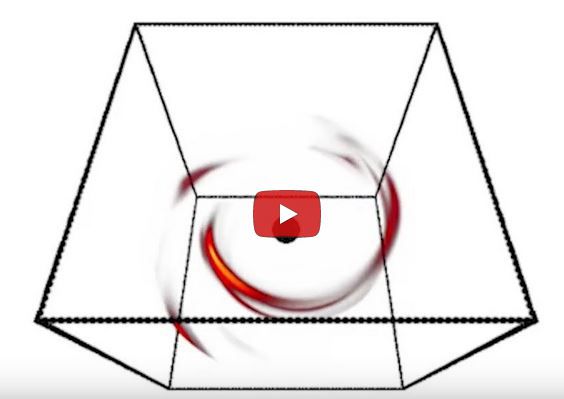

<Sketching on a paper napkin> “Fair enough. Okay, here’s what the potential energy curve looks like, sorta. There’s hydrogen atom A over there at the right-hand end of the curve. B‘s a second hydrogen on the left and heading inwards. With me?”

“So far.”

“Right. Now, B comes roaring in with some amount of kinetic energy and hits the potential energy bump where those electron clouds overlap. If it has enough kinetic energy to overcome that barrier, it keeps on going. Otherwise it bounces back with the kinetic energy it had maybe minus some that A picked up in the recoil.”

“So the first barrier is the electron‑electron repulsion, but the potential dips in the middle where the clouds merge and that’s where molecules happen.”

“Right, Sy. But then there’s the second barrier as B‘s positive charge encounters A‘s. Inverse‑square law and all that, it’s an enormous hurdle. Visualize lots of Bs with different kinetic energies running up against that wall again and again until finally, if the pressure’s high enough, one gets past and the fusion releases more energy than the winning B had originally. The higher the wall, the fewer Bs hit As per unit time and the slower the reaction.”

“Looking at the before‑and‑afters, the reaction only happens if energy’s released, but how fast it goes is that barrier’s fault.”

“Perfect, Vinnie. Take RDX, for example. You’re right, it’s touchy. If you’ve got the pure stuff, never look at it cross‑eyed unless you’re behind a blast shield. Lots of energy released, very low energy of activation.”

“But like I said, you can shoot a gun at it, no effect.”

“That wasn’t pure RDX, it was probably some version of C‑4.”

“Yeah, C‑4, don’t know any of the details.”

“C‑4’s explosive is RDX, but it’s also got some plasticizer for that putty consistency, and a phlegmatizer. I love that word.”

“Phlegmatizer? That’s a new one for me.”

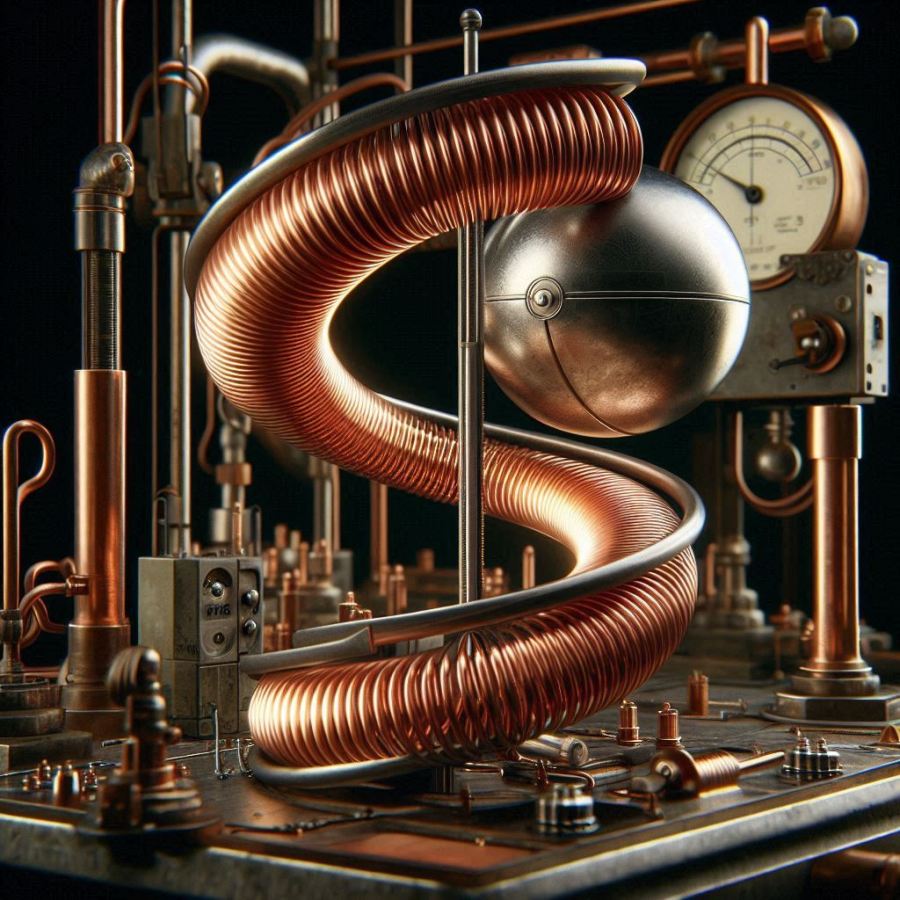

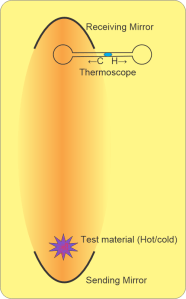

“It’s an additive to keep the explosive calm — phlegmatic, get it? — until it gets excited on purpose, which is the detonator’s job.” <scribbling on a stack of paper napkins> “Okay, here’s that same activation energy curve, an RDX particle on the right, and an incoming shock wave. The gray region is the phlegmatizer, usually paraffin or a heavy oil. Think of it as a shock absorber, absorbing or deflecting the shockwave before it can activate the explosive. A detonator’s designed to activate and erupt so quickly that its shock peak arrives before the phlegmatizer can spread it out.”

“Like they say, timing is everything.”

~ Rich Olcott