Jeremy gets a far‑away look. ”It’s gotta be freakin’ noisy inside the Sun.” just as our resident astronomer steps into Cal’s Coffee.

“Wouldn’t bet that, Jeremy. Depends on where you are in the Sun and on how you define noise.”

Vinnie booms, quietly. ”We just defined it, Cathleen. Atoms or molecules bumping each other in compression waves. Oh, wait, that’s ‘sound,’ you said ‘noise.’ Is that different?”

Susan slurps the last of her chocolate latte. ”Depends on your mood, I guess. All noise is sound, but some sound can be signal. Some people don’t like my slurping so for them it’s noise but Cal hears it as an order for another which makes him happy.”

“Comin’ up, Susan. Hey, Cathleen, maybe you can slap down Sy. He said spiral galaxies have something to do with sound which don’t make sense. Set him straight, okay?”

“Sy, have you all settled that sound isn’t limited to what humans hear?”

“Sure. Everybody’s agreed that infrasound and ultrasound are sound, and that Bishop Berkeley’s fallen tree made a sound even though nobody heard it. That’s probably what got Jeremy thinking about sound inside the Sun.” Jeremy nods.

“Then Vinnie’s definition is too limited and Sy’s statement is correct. Probably.”

That gets a reaction from everyone, though mine is a smile. ”Let ’em have it, Cathleen.”

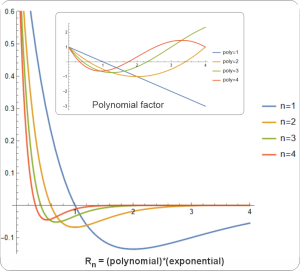

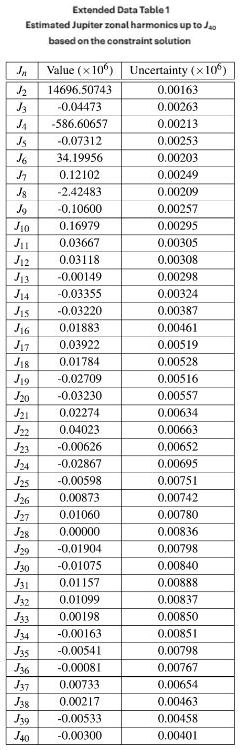

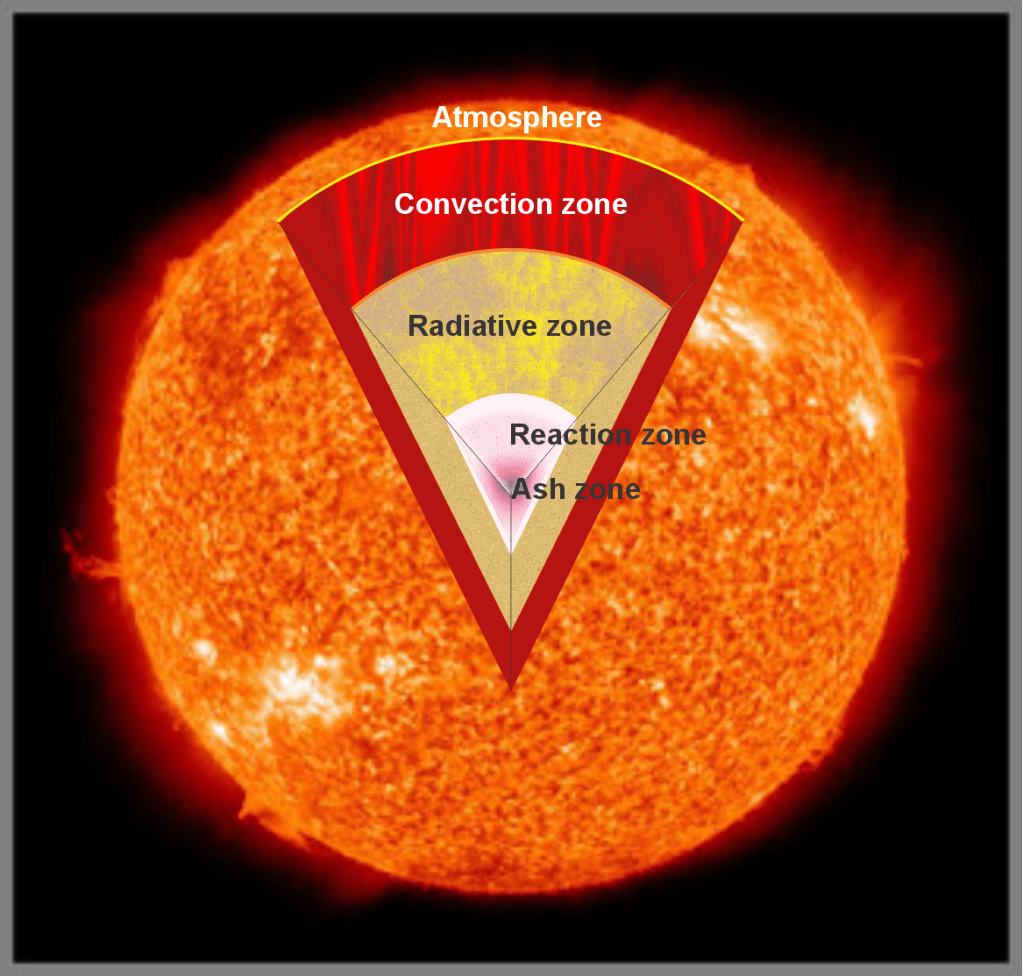

“Okay. Let’s take Jeremy’s idea first and then we’ll get to galaxies.” <fetches her tablet from her purse and a display on her tablet> “Here’s a diagram of the Sun I did for class. If you restrict ‘sound‘ to mean only coherent waves borne by atoms and molecules, there’s no sound in the innermost three zones. The only motion, if Sy grants I can call it that, is photons and subnuclear particles randomly swapping between adjacent nuclei that are basically locked into position by the pressure. Not much actual atomic motion until you’re up in the Convection Zone where rising turbulence is the whole game. Even there most of the particles are ions and electrons rather than neutral atoms. Loud? You might say so but it’d be a continuous random crackle‑buzz, not anything your ears would recognize. Sound waves as such don’t happen until you reach the atmospheric layers. Up there, oh yes, Jeremy, it’s loud.”

Geologist Kareem is a quiet guy, normally just sits and listens to our chatter, but Cathleen’s edging onto his turf. ”How about seismic waves? If there’s a big flare or CME up top, won’t that send vibrations all the way through?”

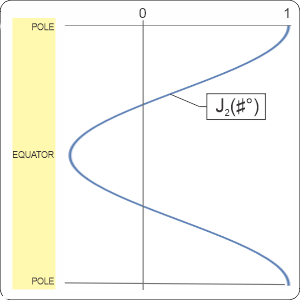

“Good point, Kareem. Yes, the Sun has p and s waves just like Earth does, but they travel no deeper than the Convection Zone. A different variety we may not have, g waves, would involve the core. Unfortunately, theory says g waves are so weak that the Convection Zone’s chaos swamps them. Anyway, the Sun’s s, p and g waves wouldn’t contribute to what Jeremy would hear because their frequencies are measured in hours or days. Can I get to galaxies now?”

“Please do.”

“Thanks.” <another display on her tablet> “Here’s a classic spiral galaxy. Gorgeous, huh? The obvious question is, is it winding in or spraying out? The evidence says ‘No‘ to both. The stars are neither pulled into a whirlpool nor flung out from a central star‑spawner. By and large, the stars or clusters of them are in perfectly good Newtonian orbits around the galactic center of gravity. So why are they collected into those arms? Here’s a clue — most of the blue stars are in the arms.”

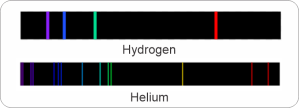

“What’s special about blue stars?”

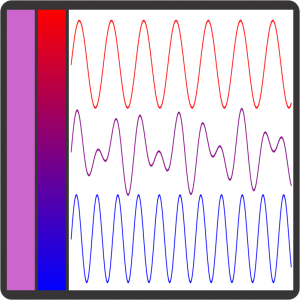

“In general, blue stars are large, hot and young. Our Sun is yellow, about halfway through a 10‑million‑year lifetime. The blue guys burn through their fuel and go nova in a tenth of that time. Blue stars out there tell us that the arms serve as stellar nurseries. It’s not stars gathering into arms, it’s galaxy‑wide rotating waves of gas birthing stars there. There’s argument about whether the wave rotation is intrinsic or whether there’s feedback as each wave is pulled along by star formation at the leading edge and pushed by novae at the trailing edge. Sy’s point, though, is that an arm‑dwelling old red star would experience the spinning gas density pattern as a basso profundo sound wave with a frequency even lower than the million‑year range. Right, Sy?”

“As always, Cathleen.”

~~ Rich Olcott

- More thanks to Alex.