From: Robin Feder <rjfeder@fortleenj.com>

To: Sy Moire <sy@moirestudies.com>

Subj: Bad diagram

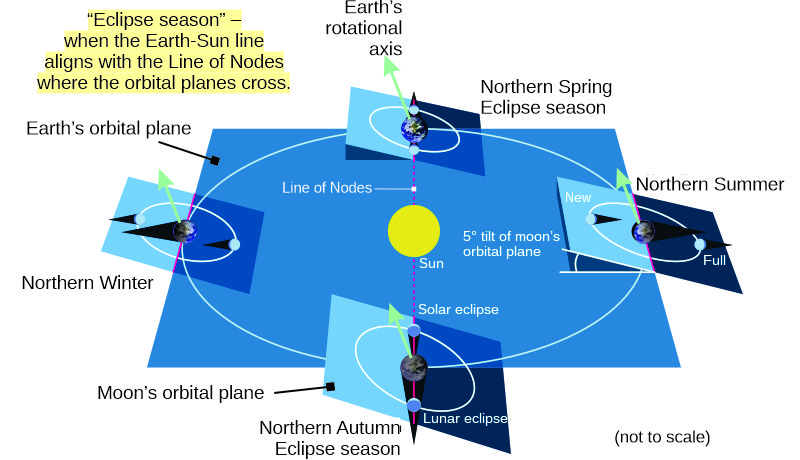

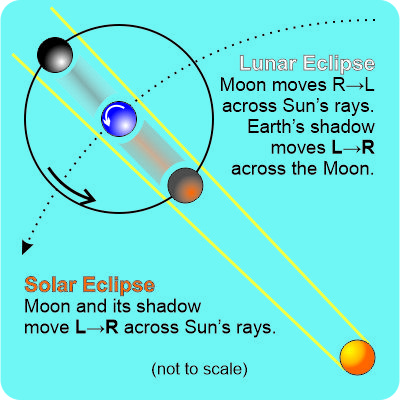

My Dad said I should write you about the bad video that is in your “Elliptically Speaking” post. It shows a circle around a blue dot that’s supposed to be the Earth, and an oval shape that’s supposed to be the Moon’s orbit around the Earth, and blinking thingies that are supposed to show what eclipses look like. I took a screen shot of the video to show you. But the diagram is all wrong because it has two places where the Moon is far away from the Earth and two places where the Moon is closer and that’s wrong. All the orbit pictures I can find in my class books show there’s only one of each. Please fix this. Sincerely, Robin Feder

From: Sy Moire <sy@moirestudies.com>

To: Robin Feder <rjfeder@fortleenj.com>

Subj: Bad Diagram

You’re absolutely correct. That’s a terrible graphic and I’ll have to apologize to Cathleen, Teena and all my readers. Thanks for drawing my attention to my mistake. When I built that animation I was thinking too much about squashed circles and not enough about orbits. I’ve revised the animation, moving the Earth and its circle sideways a bit. Strictly speaking, Earth and the Moon both orbit around their common center of gravity. Also, the COG should be at one focus of an ellipse. An ellipse has two foci located on either side of the figure’s center. However, both of those corrections for the Earth‑Moon system are so small at this scale that you wouldn’t be able to see them. I drew my oval (not a true ellipse) out of scale to make the effect more visible.

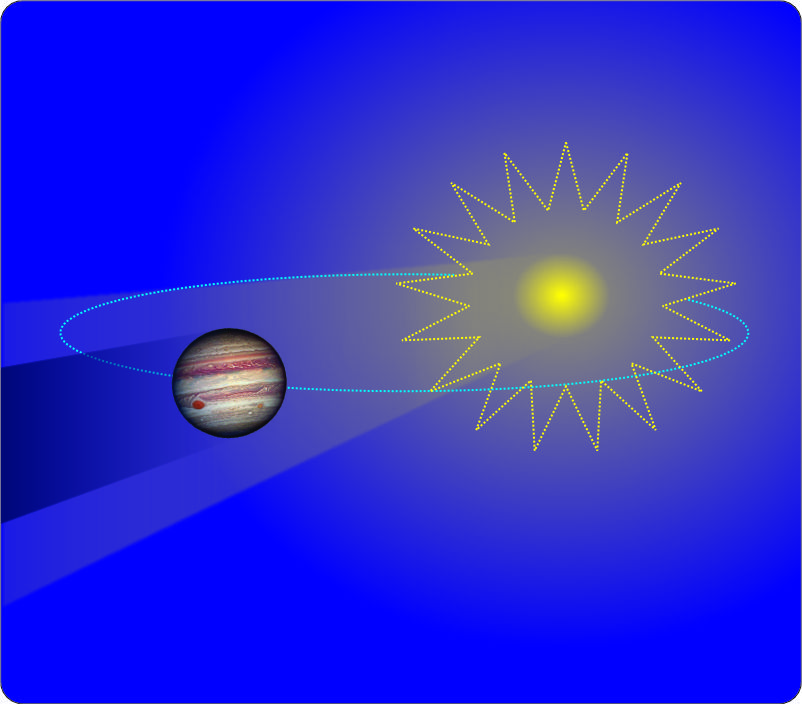

Moving the oval so that there’s only one close place and one far place (astronomers call them perigee and apogee) meant that I also had to move the blinking eclipse markers. I think the new locations do a better job of showing why we have both annular and total eclipses. You just have to imagine the Sun being beyond the Moon in each special location so that the eclipse shadow meets the Earth.

I’ve swapped out the bad diagram on the website. Here’s a screenshot of the better diagram I’ve put in its place.

Please remember to use proper eclipse-viewing eyewear when you look at this October’s annular eclipse. And give my regards to your Dad.

~~ Rich Olcott

- Thanks to Ric Werme for gently pointing out my bogus graphic.